|

| Figure 1. Note the symmetrical spherical particle design in this composite resin (Estelite Sigma Quick [Tokuyama Dental America]). This makes this material easier to manipulate, blend aesthetically, and polish. This particle design also creates smooth surfaces and stable restorations. |

Dental practitioners are encouraged to use a composite material for the first time by an advertisement, a review, or word of mouth. Continued use of that restorative product is determined by the comfort zone the dentist attains with that material. Smoothness, a shade-blending effect for optimal aesthetics, nonstick handling, and an ability to polish easily are among the properties that clinicians look for in determining their go-to materials.

The Importance of Filler Particle Design

The size and shape of composite filler particles are vital to creating optimal success with the material. Most brands of composites contain irregularly shaped and sized fillers. This makes polishing and shade-blending a difficult challenge. In this article, a pair of clinical case examples will showcase the use of a recently introduced composite (Estelite Sigma Quick [Tokuyama Dental America]) that has 100% spherical fillers with an average particle size of 0.2 μm.

In Figure 1, one can note the sand-like spheres instead of particles with irregular edges.1 This particle design leads to smooth and more easily polished restorations. It also contributes to longevity and excellent physical properties. The 100% spherical fillers allow blending within several shades to create an excellent transition between tooth structure and composite. Particle diameters of 0.2 μm are known to produce the best balance of material properties and aesthetics.2 Well controlled equivalent particle size allows these composites to absorb and blend in with light reflected off surrounding teeth, creating a true chameleon effect.

Wear resistance is also enhanced with a smaller, spherically shaped particle design. Wear from the opposing arch is virtually zero compared to similar composites. In addition, wear to opposing teeth is truly minimal. Laboratory tests have shown that gloss is retained, even after 5,000 cycles of abrasion on the surface of the composite.3

Abrasive forces can “pluck out” the chunks of nonspherical fillers, leaving behind craters that are not as polishable as a smooth surface. Due to their shape, spherical fillers can rotate and move during polymerization. Therefore, there is less polymerization shrinkage and less marginal leakage between the restoration and cavity walls. Polishing nonspherical fillers can lead to voids in polished surfaces that may cause staining and leakage in the future.

Aesthetic Characteristics

Opalescence that is similar to natural tooth structure is easier to attain with spherically filled composites. High gloss retention is observed as well due to tooth-like diffusion and refraction. The spherical particle structure leads to a higher glossiness and enamel-like reflection/refraction compared to composites with an irregular particle structure.4 Higher diffusion and light refraction results in a material that will offer the ability for excellent aesthetic blending with adjacent tooth structure. Spherically filled composites reached 90% glossiness after only one minute of polishing, compared to a prominent composite material with irregular filler size that achieved 70% glossiness in the same period of time.5,6

CASE 1

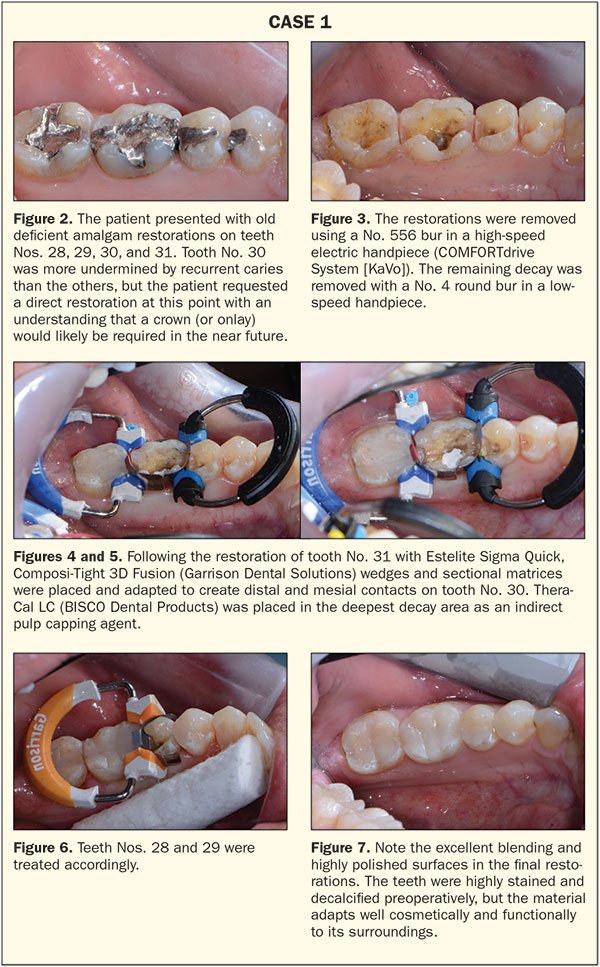

A patient presented with failing amalgam restorations on teeth Nos. 28 to 31 (Figure 2). She requested replacements for all 4 amalgam restorations. The patient was told that tooth No. 30 was quite undermined and that a crown would be the restoration of choice. However, she still opted for replacement of the amalgam with a direct composite filling. All 4 teeth presented with areas of decalcification. She was told that color match could be difficult due to the multiple shades observed in the surrounding tooth structure.

The patient was given infiltration anesthesia buccal to tooth No. 30 (Articaine 4% [Septodont]) and a mandibular block injection (Lidocaine 1.8%). Prior to the injection, the anesthetic used for the mandibular block was buffered (Onset [OraPharma]), carefully following the manufacturer’s instructions. The author’s clinical experiences with this added step have demonstrated that buffering the anesthetic provides more rapid and effective anesthesia, particularly for mandibular blocks.

The amalgam restorations were removed using a No. 556 carbide bur in an electric high-speed handpiece (COMFORTdrive System [KaVo]) (Figure 3), and all of the remaining decay was removed using a No. 4 round bur in a slow-speed handpiece. Caries removal was then verified using a caries indicator paste (VistaRed Caries Indicator [Vista Dental Products]). The deepest decay area was covered with a thin layer of TheraCal LC (BISCO Dental Products) as an indirect pulp cap/barrier prior to composite placement. Prepared areas were cleaned with a chlorhexidine gluconate disinfecting scrub (Consepsis [Ultradent Products]) that also reduces potential post-op sensitivity.

|

The enamel was selectively etched with 35% phosphoric acid gel (Ultra-Etch [Ultradent Products]) for 15 seconds. Next, a single component fluoride-releasing bonding adhesive (Bond Force [Tokuyama Dental America]) was scrubbed onto exposed dentin and enamel surfaces for 20 seconds. The wetted areas were then gently dried with oil-free air for 5 seconds and then dried for an additional 5 seconds with a moderate and stronger stream of air. The bonding agent was light cured for 10 seconds (Bluephase [Ivoclar Vivadent]).

The restorations were placed incrementally to allow for optimal interproximal contacts. Composi-Tight 3D Fusion (Garrison Dental Solutions) wedges and sectional matrices were placed and adapted (Figures 4 to 6). Tooth No. 31 was restored first, followed by tooth No. 30 and then teeth Nos. 28 and 29. In each case, a flowable composite (Surefil SDR flow+ [Dentsply Sirona Restorative]) was added to the proximal box areas, and a small layer was placed on the occlusal floor. Estelite Sigma Quick composite was then placed in 2 shades due to the decalcification and tooth discoloration. Initially, OA2 opaque shade was placed, followed by enamel shade A1. Estelite Sigma Quick has an extended working time (90 seconds or more under ambient light) and it is nonsticky with good packability.

Finishing and polishing was easily accomplished using Rally Mini Polishers (Garrison Dental Solutions) and Sof-Lex Spiral polishers (3M) (Figure 7).

CASE 2

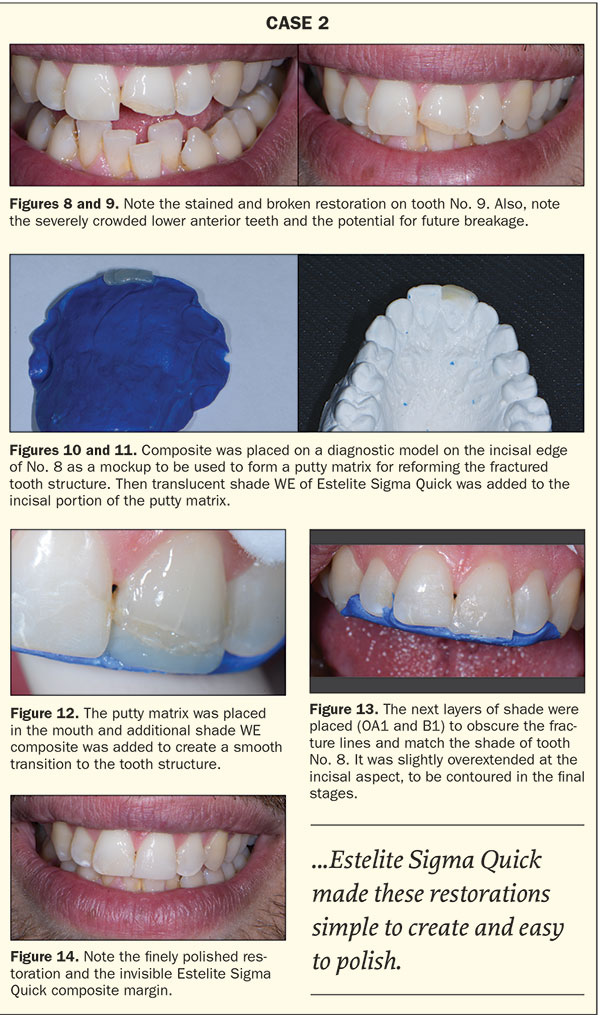

A patient appeared with a broken composite filling on tooth No. 9, which had been initially restored following an accident 10 years earlier. Tooth No. 8 presented with a chipped and stained composite restoration as well, but the patient refused treatment on this tooth (Figures 8 and 9). Further treatment was suggested, including, but not limited to, orthodontic care, but the patient refused this as well. The patient was advised that his bite-related issues could lead to a shortened lifetime of any restoration and that a nighttime appliance would be essential to protect any restoration if orthodontic treatment was not initiated.

At the patient’s initial appointment, maxillary and mandibular alginate impressions were taken. After these models were poured, composite resin was added to recreate the broken incisal and proximal edges of tooth No. 9 on the maxillary model. A palatal matrix was then created using a fast-set putty impression material (Virtual Putty [Ivoclar Vivadent]). This matrix is an indispensable aide in restoring Class IV incisal edge damage (Figures 10 and 11).

The remainder of the old restoration was removed with a No. 556 high-speed carbide bur. The labial margin was established with an irregular long bevel to hide the marginal area using a course diamond (No. 1516.8 [Microcopy]). Labial and palatal areas were then sandblasted (MicroEtcher II [Zest Dental Solutions]), and the cavosurface margins were etched using a 35% phosphoric acid gel (Ultra-Etch [Ultradent Products]). This was followed by application of the self-etching bonding adhesive Bond Force.

|

The supra-nano spherical particle structure of Estelite Sigma Quick makes it an excellent option for anterior as well as posterior restorations. It was determined that 2 or 3 shades would work best for this restoration. Estelite Sigma Quick’s excellent ability to blend in allows for treatment success in one shade or with multiple shades and tints. It should be noted that it also stays in position with no obvious slumping, making it easy to handle for restorations involving anterior teeth.

The palatal matrix was then placed behind the upper incisors. The lingual shelf was placed on the matrix, using Estelite Sigma Quick shade WE with a carver (Hollenback 6 [Premier Dental Products]) (Figure 12). Shade OA1 was placed over the beveled labial margin in an extremely thin layer to conceal the labial fracture line. Next, Shade B1 was also placed in a thin layer to form the final contours of the restoration (Figure 13). A composite instrument (Microfil composite instrument Gold [Almore International]) was used to create a smooth and continuous layer. This was followed by a thin natural bristle paint brush to achieve prepolish contours. All the surfaces were light cured for 10 seconds using the Bluephase curing light.

The restoration was initially smoothed using a flame-shaped extra fine diamond polishing bur (Microcopy). Line angles and further anatomy were created using Super-Snap Rainbow Polishers (Shofu Dental). The final polish was accomplished by a silicone polishing brush and felt discs with Enamelize Polishing Paste (Cosmedent) (Figure 14). The creaminess and excellent handling properties of Estelite Sigma Quick made these restorations simple to create and easy to polish.

CLOSING COMMENTS

The author has been using Tokuyama’s Estelite Sigma Quick, a supra-nano scale composite, for the past 6 years and has been extremely happy with its properties and long-term success. Working with a 100% spherical filler composite has been a most pleasant experience. It possesses the aesthetic qualities and handling characteristics that clinicians are looking for in a composite restorative material.

Furthermore, in the rapidly changing world of dentistry, it is rare to find a material that stands the test of time. Newer materials aren’t necessarily better. It is up to the practitioner to learn about the properties, benefits, and drawbacks of the material options available. The ideal composite handles well, is creamy and easy to manipulate, blends well, and lasts a long time without volumetric or marginal change. Spherical supra-nano composites fall into this category.

This class of composite resin materials deserves to be tested by the astute clinician as a versatile and quality material option for both posterior and anterior direct composite restorations. The only way to truly judge a dental product is to try it!

References

- Source: Tokuyama Research and Development Center, Japan.

- Yuasa S. Composite oxide spherical particle filler. DE: The Journal of Dental Engineering. 1999;89:33-36.

- Inoue G, et al. Wear resistance of new composite resin (first report). Journal of the Japanese Society for Dental Materials and Devices. 2007;26:116.

- Kurokawa H, et al. Temporal change of polished surface of composite resin. Japanese Journal of Conservative Dentistry. 2007;50(special issue):17.

- Inokoshi S. Pursuing color matching of crown-color fillers. Dental Outlook. 1996;88:785-821.

- Inokoshi S. Color of composite resin filling—opacity and light diffusion properties. DE: The Journal of Dental Engineering. 2007:5-8.

Dr. Auster, a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine, has 30 years of experience in cosmetic and reconstructive dentistry at his private practice in Pomona, NY. In 2016, he completed 2 terms on the board of directors of the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry (AACD). He also is a member of the leadership committee and was named the AACD Humanitarian of the Year in 2015. Dr. Auster is founder and past-president of the New York Affiliate of the AACD, the Greater New York Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry. He is a Dawson Scholar and received a Concept of Complete Dentistry Award from the Dawson Academy. Dr. Auster’s volunteer work includes 9 years of volunteer dentistry in Jamaica with Give Back a Smile, Donated Dental Services, and Smiles for Life. His office has contributed more than $40,000 to children’s charities in the past 3 years. He has received a Certificate for International Voluntary Service from the ADA. He is listed as one of Dentistry Today’s Leaders in Continuing Education and is a member of the Catapult Education Speakers Bureau. He conducts hand-on workshops, webinars, and full-day seminars focusing on comprehensive dentistry and discovering renewed passion in dentistry. He can be reached at (845) 364-0400 or via email at drpauster@gmail.com.

Disclosure: Dr. Auster has received compensation from Tokuyama Dental Corporation for writing this article.

Related Articles

FDA Approves Nanofiber Flowable Composite

Composite Provides More Natural-Looking Bulk-Fill Restorations

Top 8 Composites and Composite Systems