I have a confession to make. I play Texas Hold ’em poker. I have always enjoyed games—pinochle, euchre, backgammon, chess—but nothing has held my attention like this new television and casino phenomenon. The world fell in love with the game on television (as did I) when the hole card cameras were introduced, and for once we could play along and ride the emotional roller-coaster they call poker. I read several good books on the game, its psychology, theory, and of course the math. You see, I do not play poker by feel or by instinct alone; rather, I use a series of mathematical decision matrices to aid my decision making. In short, I take a risk-based assessment of situations, likelihoods, and outcomes that affect my play…much like we should do in the dental profession.

The key to a risk-based assessment is to apply the observations, decision matrices, and probabilities before we act. Afterward it is too late. We have all started a preparation, root canal, or procedure that we feel was over our heads once we got into it. The wise ones make that call before they start, rather than discover it once they get involved. I’ll explain my risk assessment in poker very briefly, and then we will apply the same thinking to a clinical situation.

There are 225 different possible starting 2-card hands in Texas Hold ’em. Two aces are the best and a 2 to 7 of different suits is the worst. Knowing the relative value of these cards and the likeliness to improve or hold up as the winning hand until the last card is imperative in making decisions before the next 3 cards are flopped.

Your decisions in poker will be made much like in dentistry…on incomplete information. The more you can observe about others’ decisions before your own helps you decide things by providing more information with which to make a decision.

X-rays, photographs, and models serve to support our examination data in this regard as well. In Texas Hold ’em, by calculating the percentage probability of making the best hand with 2 and then one card left to play, I can compare the pot odds and my hand improvement odds and make another decision. If the money bet into the pot was $100 and I needed to call the bet with $10 more, my pot odds would be 10 to one. If I held 2 hearts and 2 came on the flop, the chances of improving my hand and making a flush with 2 cards to come is 38%, or nearly 2.5 to one. I would call the bet easily because my pot odds at 10 to one make the odds for improving my hand mathematically favorable. I am actually applying a risk-based assessment evaluation that helps guide my decision making.

RISK-BASED ASSESSMENT IN DENTISTRY

|

|

|

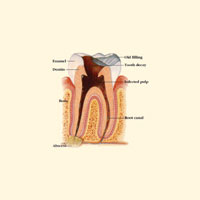

Figure 1. Diagram of endodontic abcess. |

Figure 2. Endodontically treated tooth with additional surgical fill. |

|

|

|

Figure 3. Mandibular overdenture with 3 FDA-approved ERA Implants and 2 transitional implants that allow for immediate loading the day of surgery. |

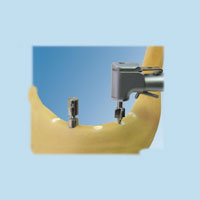

Figure 4. Implant Logic Systems’ surgical guide for ERA Implant placement. |

|

|

Figure 5. On the left, ERA Implant with Black Processing Male. On the right, pictured with White Active Retention Male, the arrow shows the 0.4-mm resilient spacer area. |

Dentistry offers several good examples of this decision matrix being applied. Some dentists perform root canal treatment, but not necessarily all of the cases that they could (Figures 1 and 2). They often choose certain teeth that present with an easier series of steps and outcomes that improve their odds of successful treatment. This is a risk-based assessment. TMD cases, comprehensive reconstruction, and periodontics have examples as well. Extractions (especially third molars) are an excellent example. After considering a number of scored parameters (age, radiographic appearance, disposition of the patient, overall health, etc), one makes a reasonable decision regarding whether to proceed with treatment or to refer. You may not have written this assessment down, or applied a mathematical score to the parameters, but you did create a decision matrix even if it was unconscious.

I have recently begun to perform a surgical procedure that is clearly outside my traditional comfort zone: placing implants for immediate load overdenture cases. I could not do this without a risk-based assessment. I stumbled upon a very viable treatment protocol that could provide a much-improved prosthetic solution for a more affordable cost than traditional implant-retained overdentures. It also had the potential of significant financial gain for the practitioner.

Like many of the “seems-too-good-to-be-true” stories I have heard, I listened to a presentation about this with some healthy skepticism. My cynical psyche was summarily disappointed quite rapidly, though, when the discussion began with the term risk-based assessment. This immediate load implant-retained overdenture protocol using ERA Implants and Attachments (Sterngold) had several good things in its favor (Figure 3). Here are the reasons I like Sterngold’s protocol:

- It was a $4,000 to $6,000 solution for patients rather than a $15,000 to $20,000 conventional implant-retained overdenture fee.

- It had partnered with CareCredit to help patients afford treatment.

- It had a great marketing kit to help me attract the patients I would serve.

- Sterngold has the only system with FDA approval

for permanent mini implant placement; all the others are for “long-term stabilization.” - The cost for implant parts was low ($600 to $800 per arch).

- The profit potential was high from each case.

- It had a surgical guide available from Implant Logic Systems that simplified im-plant site selection and placement (Figure 4).

- It had the ERA Sys-tem with true resiliency de-signed in using the 0.4-mm spacers (Figure 5).

- There was a mentor over-the-shoulder system to help me at my office when I was ready to take on my first cases.

- Perhaps most importantly, I was not told that I could treat every case that came along. A risk-based assessment would help me stay out of harm’s way when making clinical decisions on when—and when not—to treat.

|

|

|

Figure 6. Acetate overlay showing adequate room for fixtures using 125% radiographic magnification adjustment. Note the distance from the mental foramen even for the 15-mm ERA Implant. |

Figure 7. Using the 4-mm surgical punch in a broad surface of the mandible in lieu of an incision or flap procedure to gain access for ERA Implant placement. |

Some patients are healthy enough. Some mandibles and maxillas are large enough (both in width and depth). Some bone is dense. Some nerves and osseous irregularities are far from the surgical site. And, un-fortunately, some are not. That is the key in a risk-based assessment. If we understand the procedures, and we can evaluate the patient and the sites prior to doing a punch or laying

a flap, we can determine which cases we are comfortable with and capable of treating, and which we are not (Figures 6 and 7).

Now, do not misunderstand me. My good friend and Sterngold surgical mentor, Neil Thomas, DDS, can treat many cases that I would not. His “go” and “don’t go” signs are farther apart than mine. I think of it like a stoplight. We both have green and red lights that tell us without question when to proceed and stop. They are just in different places. Neil’s yellow light is broad and long. He can treat many challenged mandibles and maxillas that would be a big red light for me. That is fine. It is less about where his lights are and more about assessing where mine are. I might prefer a surgical guide at first and to do only cases that could utilize a punch incision instead of laying a flap (about 17% of the time).

|

|

|

Figure 8. Using the Countersink/ Drill (Sterngold) and 0-degree alignment device to prepare a second site for an ERA Implant. |

Figure 9. Using ERA PickUp material to capture the ERA Males in their metal housings over the transitional implants on the day of surgery. Black Processing Males without metal housing cover the uncaptured 3.25-mm permanent ERA Implants. They will be left to osseointegrate fully before picking them up at a later date. |

|

|

|

Figure 10. After coring out the Black Processing Male Attachments, the White Active Retention Males are placed with a special tool into the metal housing picked up in the procedure above. |

Figure 11. Neil Thomas, DDS, and surgical assistant Carrie Davies working on an ERA Implant overdenture patient. |

Having Neil at my side during my first few forays into the world of implant placement was helpful in finding the position of my stoplights. In the hands-on typodont course and lecture that Sterngold gives, there is excellent instruction, documentation, and practice to “teach” me how to place these fixtures (Figures 8 to 10). Just because I was “taught” everything does not mean I had “learned” anything. And therein lies the difference. The cost of entry is not steep to acquire the armamentarium. The real question is, “Will I take out my new surgical handpiece and kit and place the first one after just practicing on acrylic for a day?” May I answer for most of us, “When donkeys fly!” The kit and noninterest-bearing capital investment would likely sit quietly gathering dust in a hidden enclave of my office were it not for the mentor program.

In the one morning that you can schedule 2 surgeries (Neil does 2 in just more than an hour each) you can generate enough income to pay for the kit, handpiece, and Neil to come and watch to make sure we stay the right course. His insight and understanding of our implementation barriers to new technologies and procedures is awesome. I felt confident both in the assessment we made to-gether prior to the Saturday morning appointment as well as the protocol itself (Figure 11).

WHEN DONKEYS DO FLY

Take it upon yourself to use a risk-based approach to clinical decision making in your practice. Find mentors familiar with the procedures you wish to undertake. Observe them and learn from them. Invite them to oversee your first steps into this new and exciting, yet uncharted ground. You do it every day with dozens of procedures, materials, and decisions that you make. Instead of the old adage, “tell, show, do,” perhaps we should consider “listen, watch, do with oversight first.” In fact, I think that is how we learned what we do know in dental school—the caring eye of the instructor helpfully guiding you to correctness at every turn. Well, at least that was their intent.

Sometimes old dogs like me can learn new tricks. Sometimes donkeys do fly. But they check the weather and file a flight plan.

Oh yes, and they do their first flight under the watchful eye of one who has gone before.

Dr. Murphy is a featured presenter for the National Dental Network and the National Lab Network, and he lectures internationally on a variety of dental, clinical, and behavioral subjects. He practices part time in Rochester Hills, Mich, and teaches at The Pankey Institute in Key Biscayne, Fla, where he serves as the director of professional relations. He can be reached at mmurphy@pankey.org.