Utilization review, statistically based, as defined by the ADA Glossary included in the Current Dental Terminology CDT 2007-2008, is “A system that examines the distribution of treatment procedures based on claims information. In order to be reasonably reliable the application of such claims analyses of specific dentists should include data on type of practice, dentist’s experience, socioeconomic characteristics, and geographic location.” Utilization management is defined by the same glossary as “A set of techniques used by or on behalf of purchasers of health care benefits to manage the cost of health care prior to its provision by influencing patient care decision-making through case-by-case assessments of the appropriateness of care based on accepted dental practices.”

|

|

Illustration by Nathan Zak |

Insurance carriers employ utilization data as a basis for many aspects of dental plan design and usage. Utilization data has also traditionally been drawn upon to assess treatment variations against what a carrier has established as a “norm.” If a dentist performs certain procedures at a higher rate than other dentists in his or her zip code, a carrier may decide that the dentist’s practice patterns are not typical. Dentists who practice atypically are undesirable in networks. They can strain plan resources. In addition, reporting more procedures than others means “overutilization” to most carriers, implying that the procedures being claimed are probably not necessary or are being reported incorrectly. A dentist who is an “overuser” may be audited or face other consequences.

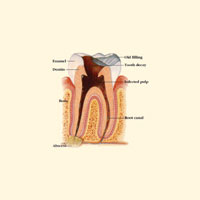

A major problem with utilization statistics is that they do not reflect the whole picture. A general dentist may report more endodontic procedures than others in his or her zip code because the clinician refers fewer cases out. A general dentist may report more periodontal maintenance procedures because he or she has a superior screening and treatment system to identify periodontal patients.

While it is one thing to label a dentist as an overuser, it is another to use a dentist’s practice profile as a method of distinguishing a “good” dentist from a “deviant” dentist (deviant here meaning practicing outside the “norm”). When utilization data identifies a deviant dentist, that dentist may be branded (as Delta of Minnesota did in 2000) as not showing “an orientation to provide economic value in treatment approaches.” Such dentists had their fee reimbursements frozen by Delta of Minnesota that year. Dentists who were shown to be extremely outside the norm had their fee reimbursements reduced!

While the year 2000 has long passed, the evolution of utilization review and its implications has continued. Although the term utilization review is still prevalent, a new incarnation of the concept is being called P4P or Pay for Performance. In a special column in the ADA News on February 13, 2007, P4P was explained. According to the article, “A new initiative with strong backing by the federal government has been introduced that, if successful, will have a major impact on the delivery of dental care…That initiative is called pay for performance; a reimbursement plan built upon the philosophy that those who perform well should be reimbursed more than those who perform at a lower level.” P4P, on the medical side, has already been embraced by medical insurers, as well as the government in its Medicare and Medicaid plans.

While explanations abound as to the true elements of “performing well,” it appears that the driving force behind P4P is money, just as it has always been with utilization review. It is known that healthcare costs in the United States are among the highest in the world. Managed care and the use of networks of providers have held prices down in the past. However, physicians, hospitals, clinics, and dentists have had their fees squeezed year after year. There is little left to reduce. Enter, “consumer purchasing of healthcare” and the need to “differentiate among providers.” According to the ADA, under a P4P plan, providers in a network are given incentives to meet evidence-based performance criteria. In order to work with the plan, not only must they meet the criteria, but they must report their performance using office management systems (computerized systems and electronic records) that track patient care. Incentives for dentists to provide “quality” treatment are another aspect of P4P. According to the ADA News, these incentives are typically both financial and reputational. The financial incentive is in the form of increased reimbursement for “preferred behavior.” The reputational aspect is a public release of provider performance data that can affect a provider’s reputation in a community.

PREFERRED BEHAVIOR: WHAT IS IT?

“Preferred behavior” appears to be based on 4 elements in a P4P plan. These are performance measures, data collection, performance targets, and performance incentives.

• Performance measures are typically thought of as an account of the utilization of services and the cost to provide these services. In other words, how many services has a dentist performed and what did it cost the plan to pay for these. Additionally, clinical quality and outcomes of treatment may be considered. However, there is no consensus as to how clinical quality and outcomes in dentistry might be measured fairly. On the medical side, the American Medical Association has developed 100 performance measures used to evaluate medical treatment outcomes. In the future, it is possible that the ADA and others may develop a system of dental outcomes measurement. For now, cost appears to be the main criterion of performance.

• Data collection typically refers to the quantity of claim forms processed and the codes for treatment reported on these forms. Nationally, there is a strong push for full electronic data collection in the form of an EHR: electronic health record. Electronic data maintenance of all types is a goal of both the government and insurance carriers. However, the development and acceptance of digitized records appears to be slow and erratic. Many industry watchers predicted completely computerized systems long ago, but this has not happened. Industry-wide computer program incompatibility and other issues are delaying full implementation of digitized systems. (While an electronic record may help manage data concerning patient care, a July 2007 article by Reuters reported that in a study of 1.8 billion medical doctor visits, there was no advantage of electronic records over paper charts in the quality of patient care. According to the article, there were 14 “quality indicators” for which electronic and paper records appeared to be of equal value. These included prescribing the correct antibiotic, ordering and tracking screening tests for various conditions, and supplying appropriate prescriptions for the elderly. Interestingly, when it came to prescribing statins for patients with high cholesterol, doctors using electronic records did worse than those with paper charts.)

• Performance targets are considered to be the heart of any P4P plan. Performance, also sometimes called best practice, can mean whatever a plan wants it to mean. For example, when utilization data is used as a performance criterion, a “best practice” profile might be one that provides for the least expensive treatment, as opposed to other treatment considerations. It might be doing more standard prophys and fewer root planings, or periodic exams once every 2 years instead of once annually. Best practices or performance targets can mean less treatment, depending on who is defining the practices.

• Performance incentives can have a huge impact on any plan. While reputational in-centives may influence dentists, financial incentives are key. The idea of using a financial bonus to reward dentists who are providing the “best value” under a plan is simple enough to understand. However, the concept gets complicated when it comes to deciding from where financial bonuses will come. Should the money for the “good” providers (as defined by the plan) come from the “bad” providers compensation? Should the money come from increased premiums? What about the “bad” providers? Should they be eliminated from a plan? Should they have their compensation reduced? Should they just be eliminated from receiving a bonus? With all the issues surrounding monetary rewards, it is difficult to imagine how financial incentives might actually lower the cost of care as defined as one of the objectives of a P4P plan.

NETWORK REMOVAL AND “INSURANCE FREE”

In my home state of Colorado, Delta financially rewards “good” dentists whose utilization data supports the Delta definition of comprehensive treatment. These dentists’ statistics reflect Delta’s standards of “reasonable” utilization with no hint of “overtreatment.” Dentists who do not fall into the “good” category may eventually be removed from the network. Since Delta covers 1 in 4 patients nationwide, being removed from a Delta network can be a terrific financial blow to a dentist. Many patients will leave for another dentist on the “list” because of economic pressures and an underlying distrust of a dentist who has been dropped from a plan. Pa-tients may believe that their plan is looking out for them and that the dropped dentist is “no good.” Dentists who witness the consequences of others being dropped from a network may become afraid to leave the network on their own, even if they are unhappy with their situation. An unhealthy, coercive situation can develop.

This type of atmosphere can cause many dentists to think about going “insurance free.” While this may work in some practices, many patients rely so heavily on their insurance and on the dentist’s staff to help them navigate through their benefit issues, it may be difficult to achieve. In fact, in a 2003 ADA survey it was revealed that 65% of patients seeing dentists have insurance! For these patients, no insurance would likely mean no dental care. (Even if an office decides to discontinue filing claims on patients’ behalf, as long as patients rely on their benefit plans, an office is actually never totally “insurance free.”)

Some dentists may simply want to reduce certain problems surrounding the office’s responsibilities in dealing with insurance. They may decide to become nonparticipating. Nonparticipating or nonnetwork providers are under fewer contract constraints; for example, there is no annual fee submission, no requirement to accept a maximum plan allowance, and no evaluation for “best practices.” However, patients going to nonparticipating dentists are required to pay a larger portion of the bill, and any payment check comes directly to them. Being “par” or “nonpar” both present problems for dentists. P4P plans are likely to build on, not eliminate, is-sues such as these that have surrounded dental benefits for years.

As we have seen, P4P programs and utilization review programs seem to be primarily focused on a desire to reduce costs to insurers. While P4P plans on the medical side are forging ahead quickly, such plans on the dental side are just developing their criteria. The ADA is involved in attempting to influence plan designs to address other aspects of performance rather than just insurer costs. These include the relationships among diagnosis, treatment outcomes, and patient satisfaction.

UTILIZATION REVIEW AND THIRD-PARTY AUDITS

Because utilization review is such a prominent feature in a plan’s process of “policing” contracts, dentists need to be aware of the audit process. Dental insurers may decide to audit a dentist who is flagged during a standard utilization review process or who comes to their attention for some other reason, such as a patient complaint. The audit process is designed to discover if a refund is due to a carrier, to discourage plan “abuses,” and to cut down on “deviant” claims in the future. Dentists who are faced with an audit have only their records to protect them. Without detailed and thorough patient records, whether computer or paper, the dentist has nothing to back up treatment and claims submitted. Information contained in a patient’s record should include, but not be limited to the following: reason for first visit, comprehensive data collection, complete diagnosis, treatment plan based on diagnosis, progress notes, and outcome of treatment. If treatment is performed that does not conform to the initial diagnosis, it is difficult to support treatment decisions. Documented information supporting treatment decisions is essential during an audit.

Many dentists believe that an insurance plan auditor has no right to look at patient records without the patients’ written consent. However, HIPAA specifically gives insurance plans the right to access information they think is necessary to pay claims and police their plans. Employers who purchase a plan for their em-ployees, who subsequently become your patients, give an insurance carrier this right by virtue of accepting the benefit contract. In the ADA HIPAA Privacy Kit there is a list of situations where a health plan may access private health information under HIPAA. These include the following:

- Determining eligibility and adjudicating claims for patients.

- Reviewing healthcare services for medical (dental) necessity, coverage, justification of charges, and payment history.

- Utilization review.

Previously, financial records of nonsubscribers could also be scrutinized to match up to charges made to subscribers; however, HIPAA regulations do not permit this anymore. Only subscriber financial records may be viewed.

To comply with HIPAA regulations, and to let their patients know about the dentist’s obligation to provide health information to insurance carriers and government officials, every dental office should have a “Notice of Privacy Practices” brochure where office policies are spelled out for patients.

RECORDS ARE THE KEY

As always, patient charts are the key to all aspects of dealing with insurance carriers, government agencies, and malpractice situations. Record keeping is an essential function of any dental office. Whether paper or computer, detailed records support the dentist’s diagnosis and treatment plan, as well as provide a diary of services rendered. In the arena of utilization review and P4P, records will continue to provide the most important documentation for the patient, the staff, and the dentist. Without them the dentist has no way of verifying why treatment was indicated and what treatment was accomplished. Dentists who are facing an audit by a plan might contact the ADA Council on Dental Benefit Programs, the AGD Dental Care Council, or the American Academy of Periodontology Third Party Manager. These organizations may have input to help you. In addition, your own attorney should be notified to provide any advice or support that you might require.

Ms. Tekavec is the author of the Dental Insurance Coding Handbook 2005-2008. She is the designer of a dental chart that has been endorsed by the Colorado Dental Association, as well as author of a series of patient brochures explaining various dental procedures. Still practicing as a clinical dental hygienist, she is the president of Stepping Stones to Success, a frequent lecturer at major dental meetings, and a presenter for the ADA Seminar Series. She can be reached at (800) 548-2164, or by visiting her Web site steppingstonestosuccess.com.