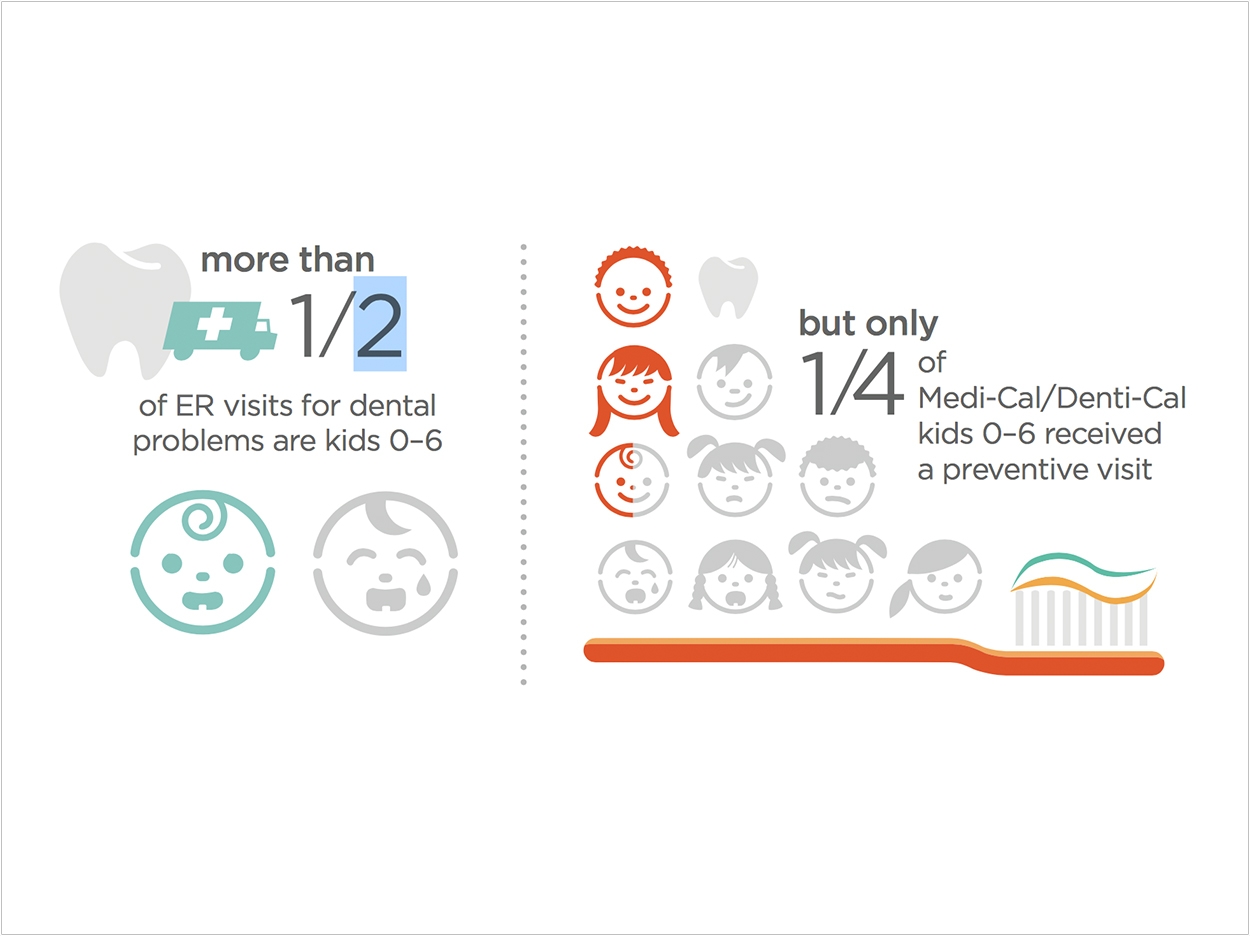

Despite efforts to increase dental visits at federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), only 21% of people who use them received dental services in 2015 and only 25% of California’s Medicaid-enrolled children younger than the age of 6 years are receiving preventive dental services, according to the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) School of Dentistry and Fielding School of Public Health. Yet researchers there have outlined recommendations for closing these gaps.

Strategies for expanding oral healthcare capacity include adding dental clinics at FQHCs that currently do not provide dental services, thereby co-locating medical and dental services, and supporting infrastructure enhancements and quality improvement, said James Crall, DDS, MS, ScD, lead author of the study and a professor of public health and community dentistry at the UCLA School of Dentistry.

The UCLA-First 5 Oral Health Program represents a model of how these strategies can achieve success in improving access and quality of care for young children, according to the researchers. First 5 LA, an early childhood advocacy organization in Los Angeles County, is funding the program.

Data from the program shows that the average number of children who are 5 years old and younger receiving dental services each month at 12 participating clinics increased by nearly 85% in the first 2 years of the project. Eight additional clinics are now participating in a second phase of the program.

Crall credits this jump in dental services to the program’s support for new oral healthcare workers known as community dental home coordinators. These individuals train clinicians and support staff to provide oral healthcare for young children and a quality improvement learning collaborative that teaches clinic teams how to deliver care more effectively by integrating the efforts of dental and medical providers.

“We are very pleased with the results thus far of our oral health program,” Crall said. “The data show that our model is working. The strategies we’ve implemented could serve as a model for oral healthcare programs across the country.”

“Young children are our greatest asset and we cannot improve their overall health without improving their oral health,” said Nadereh Pourat, PhD, coauthor of the study, director of research at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, and professor at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health and UCLA School of Dentistry.

“Our study identifies an effective strategy to integrate oral and medical care to improve the health of the most socially vulnerable children, but this strategy can also work for all young children,” Pourat said.

The researchers issued several recommendations for policymakers and program officials to increase access to high-quality primary oral healthcare services for underserved people:

- Policies could be updated to define oral healthcare as an essential, integral part of health centers’ primary healthcare services, with a clear expectation that comprehensive primary healthcare services be provided in all FQHCs;

- Congress and the Health Resources and Services Administration could give greater priority to expanding dental care service delivery within existing FQHCs by providing additional funding for facilities, personnel, and critical infrastructure elements to address obstacles;

- Government agencies could help develop more effective strategies for expanding access to dental services through partnerships among eligible health centers and community-based dental providers, especially in clinics that do not provide co-located medical and dental services;

- The Health Resources and Services Administration could expand the use of quality improvement methods and collaboratives to redesign the care delivery processes at FQHCs to achieve greater medical and dental integration within health center delivery systems and improve oral healthcare access, quality, and performance.

“FQHCs are a critical component of the safety net in California and provide primary healthcare, including preventive dental services, to our youngest and most vulnerable children,” said Crall. “For FQHCs to be successful in providing more children with recommended preventive oral health services, policymakers must address systemic barriers and augment support for FQHCs.”

“Tooth decay is an often-overlooked health problem that can impact every facet of a child’s life, often leading to poor academic achievement, deteriorating overall physical health, and social isolation,” said Ted Lempert, president of Children Now, a children’s advocacy group based in Oakland that contributed to a policy brief based on the research.

“We must provide more support to California’s FQHCs so that they will be better able to prevent and address tooth decay in young children, which will improve life outcomes for California’s most vulnerable kids,” said Lempert.

“From encouraging preschoolers to brush their teeth daily to finding low-cost dental services, many families face challenges supporting their young children’s oral health,” said Kim Belshé, executive director of First 5 LA.

“Adopting and implementing this brief’s policy recommendations will help families by integrating dental and medical preventative services and ensuring all children enter kindergarten ready to succeed in school and life,” said Belshé.

The study, “Improving the Oral Health Care Capacity of Federally Qualified Health Centers,” was published by Health Affairs.

Related Articles

Project Triples Dental Care for Underserved Children in Los Angeles

UCLA Developing Oral Health Database

Most Children on Medicaid Lack Dental Services