INTRODUCTION

Meet Carson. He lost tooth No. 9 at the tender age of 14 after a battle to resolve its developmental impaction (Figure 1) and reoccurring infections (Figures 2 to 5). He had multiple failed Maryland bridges (Figure 6), and his current dentist had told him there was nothing further they could do to help him. Carson’s orthodontist, who had been overseeing the case for 6 years, referred the family to me. When Mom called to schedule the initial visit, she said, “Our dentist has fired us, and we have no one to turn to.”

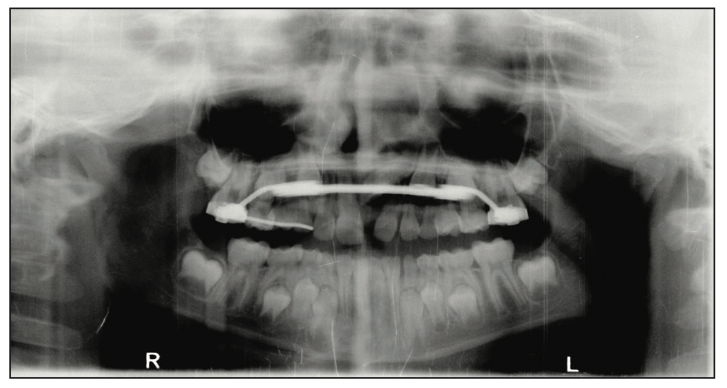

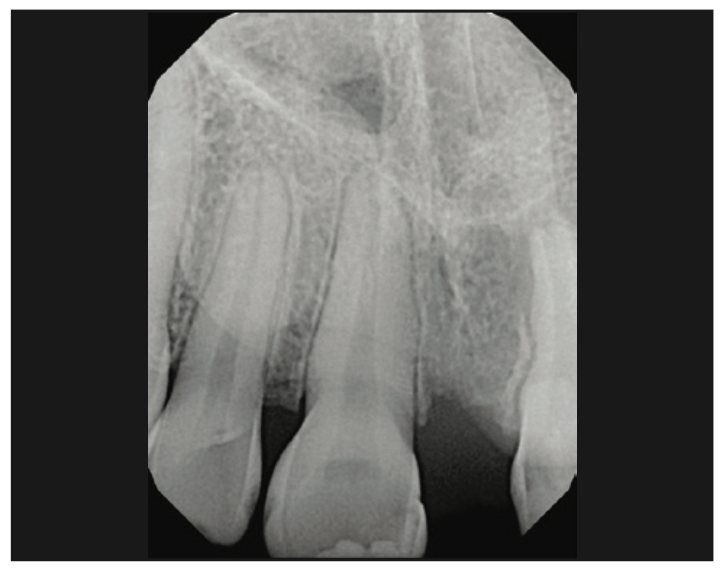

Figure 1. Panoramic x-ray showing the developmental impac- tion of tooth No. 9.

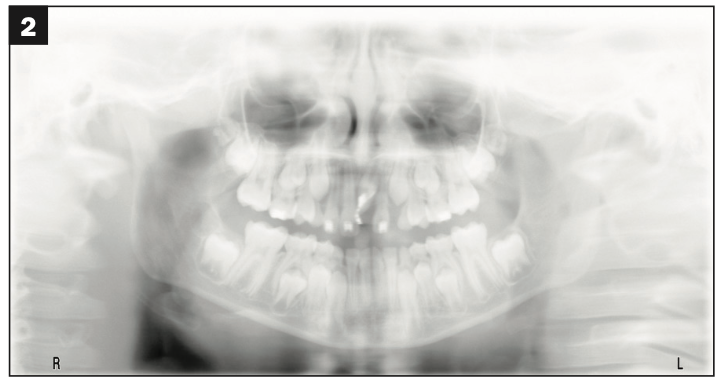

Figure 2.

Figures 2 and 3. Exposing and bonding and bringing tooth No. 9 into position were somewhat successful, but reoccurring infections at No. 9 could not be resolved.

Figure 4.

Figures 4 and 5. Even after extraction, it still took time and additional procedures by the oral surgeon to clear the infection. The loss of the tooth was catastrophic but necessary.

INITIAL PERSONAL THOUGHTS

When I met Carson, he was 16 years old and wearing an Invisalign tray (Align Technology) with missing tooth No. 9 painted in White Out. It was really heartbreaking and something I had never encountered. His self-esteem was circling the drain, and his parents were terrified these circumstances would permanently scar him. He was sullen, moody, and would barely look at me. He wore a hoodie with the hood pulled up at all of his visits with me. He couldn’t bring himself to smile for clinical photos—he honestly did not know how (Figures 7 and 8). The vivacious, confident, smart young man that his parents had raised was vanishing before their eyes. His orthodontist saw what was happening and stepped in to help by sending Carson to me.

Figure 6. One of the Maryland bridges before it failed. The family and patient had been a little underwhelmed by the aesthetics of this Maryland bridge.

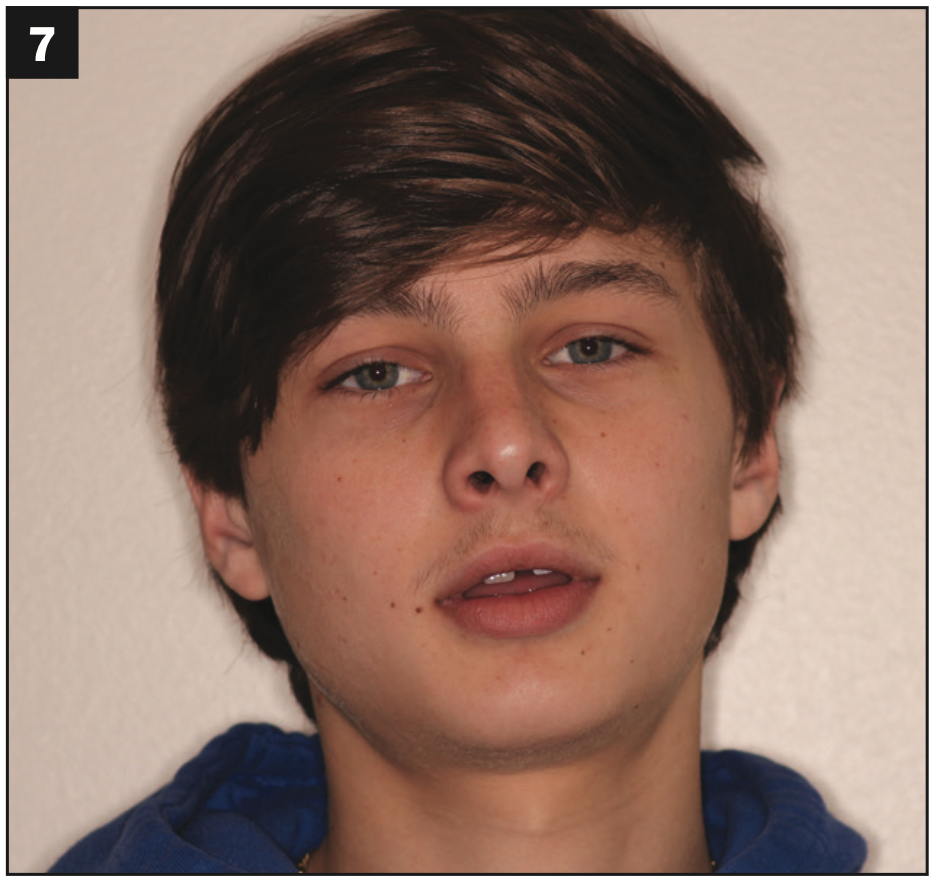

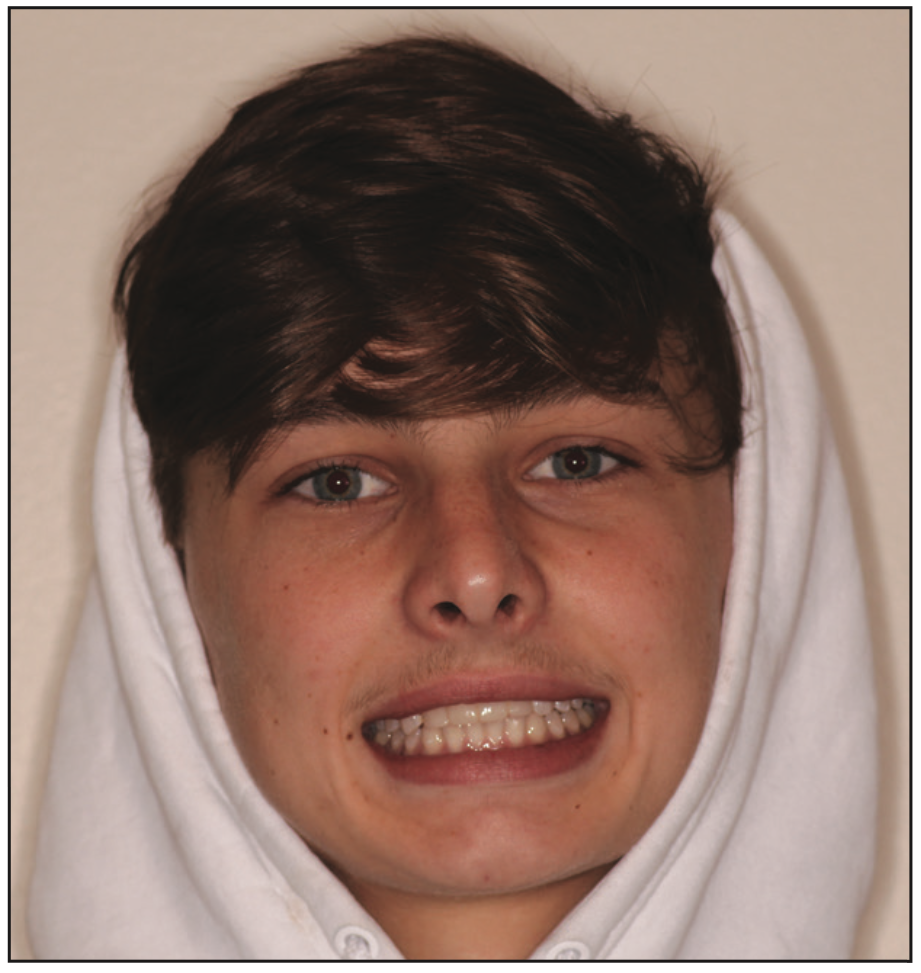

Figure 7.

Figures 7 and 8. Carson couldn’t even smile for clinical photos—he honestly did not know how. This was the best smile we could coax out of him.

DEVELOPING A PLAN

An ideal scenario when a patient is missing a tooth is the placement of a dental implant. Not only was Carson too young for this option but the space available for an implant was also too narrow both bucco-lingually, due to the destruction of the bone by the recurrent infections, and mesiodistally, as confirmed by the oral surgeon who extracted the tooth after multiple attempts to bring it into position by the orthodontist (Figures 9 and 10). The lack of adequate space for an implant was also confirmed via a CBCT scan. The orthodontist did not feel that putting any more orthodontic forces on the already compromised tooth No. 10 was a good option, especially considering the abbreviated root structure and its proximity to the site of recurrent infections. This was confirmed in the radiograph (Figure 11). Carson had already been through 6 years of orthodontics, both early/interventional and conventional, with a few pauses periodically while the endodontist and oral surgeon treated the recurrent infections at No. 9.

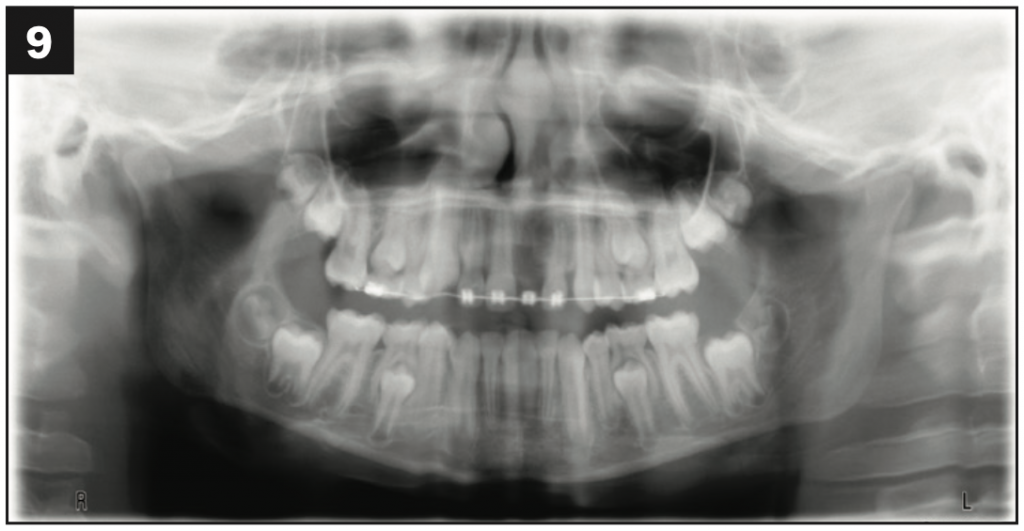

Figure 9.

Figures 9 and 10. Final orthodontic space for No. 9 and the continuing battle to resolve the infection.

After spending considerable time studying Carson’s case with an experienced and highly skilled ceramist, we feared that a new Maryland bridge was not a viable option. The factors affecting his candidacy for a Maryland bridge included the large width of the space available; the tilt and shape of the surrounding teeth; and the thick gingival tissue on the facial of the site where tooth No. 9 was missing, which would have required a very long wing (Figure 12). These factors may have contributed to the failure of 2 previous Maryland bridges and Carson being “fired” by the previous dentist. (The family was never pleased with the aesthetics of the old Maryland bridge, either [Figure 6].)

While not the most ideal, we did still have options for Carson. The parents, the orthodontist, and I began discussing crown and bridge. The downside of this option was the removal of mostly healthy tooth structure on the abutment teeth—particularly in such a young patient—for no other reason than to replace missing tooth No. 9. However, the advantage was that this option had the potential to be the most aesthetic of all available options, and it would certainly be much more stable with a better prognosis than a Maryland bridge. Carson was also at high caries risk; note the incipient interproximal lesions on the anterior teeth (Figure 11). Further, he had 2 mm of overjet, meaning that the lingual surfaces of his maxillary anterior teeth would not even need to be prepared, and the bridge would be exempt from normal occlusal forces.

Figure 11. Inadequate space for an implant for No. 9. Note the abbreviated root structure and tipping of tooth No. 10.

Figure 12. Note the thick facial tissue where No. 9 was missing, which made this site less favorable for a Maryland bridge.

Finally, it is very helpful to have an option that has fallbacks or safety nets, ie, if plan A fails, we still have a plan B. Most of the time, extracting teeth and placing implants is the final plan—if an implant fails, there aren’t usually many alternatives to that treatment option other than hoping the implant failure did not destroy bone in such a manner that would prevent an additional redo attempt at implant therapy. So while implant therapy is often the ideal solution for missing teeth, looking at cases like these, we look for a restorative plan that may work for some period of time before resorting to implants. Attempting to use the existing natural teeth first, even if they aren’t perfect, rather than just extracting them and going straight to an implant plan is often the best solution. It is often surprising how many years an alternative restorative plan can “buy” the patient prior to extractions and implant placement.

In Carson’s situation, tooth No. 10 was already compromised, and the case was made that if we continued orthodontic treatment, we risked losing that tooth as well and continuing to damage Carson’s self-esteem in the process. I told the family if we could stop ortho after 6 years of orthodontics and get an immediately excellent aesthetic result for Carson, what’s the worst that could happen—the failure of a bridge abutment? It seems (optimistically) unlikely, considering the entire maxillary anterior was not in occlusion, but if we did lose one of the bridge abutments (tooth No. 8 or 10) all of a sudden, we would have room for an implant that could serve as a cantilever bridge option. This would be our “plan B” if plan A failed. So we started talking about a conventional bridge from Nos. 8 to 10 with a porcelain veneer for No. 7 to make it symmetrical, treating as few teeth as possible. I witnessed the family’s growing excitement about trying something different for Carson.

PRESENTING THE PLAN TO PATIENT AND FAMILY

In the interest of thoroughness, which I believe all patients deserve, here are the options I gave the family.

Option 1: Placement of a crown on compromised tooth No. 10 with a pontic cantilevered off it to replace No. 9. The upside of this option was that it would be much more stable than a Maryland bridge. The downsides of this option included:

1. The removal of otherwise perfectly healthy tooth structure of No. 10 for no other reason but to replace No. 9

2. It is challenging to achieve ideal aesthetics by treating only 2 teeth on one side of the smile/midline

3. The limited ability to improve the aesthetics of tooth No. 8

4. The possibility to further compromise the already compromised tooth No. 10

One potential saving grace of this option was that we would be removing tooth structure from a tooth, No. 10, which was already compromised and had a questionable long-term prognosis. If tooth No. 10 were to break, then it would probably need to be extracted, in which case we would benefit because now we would have sufficient room for an implant.

Option 2: Placement of a conventional bridge from teeth Nos. 8 to 10 with a pontic on No. 9. I explained that in cosmetic dentistry, we always at least consider and discuss with the patient treating teeth symmetrically in the smile/on both sides of the midline for the best aesthetic outcome. For this reason, I also recommended a porcelain veneer for tooth No. 7. Downsides of this option included:

1. The removal of otherwise perfectly healthy tooth structure from teeth Nos. 7, 8, and 10 for no other reason but to replace missing tooth No. 9

2. The possibility to further compromise the already compromised tooth No. 10 (though far less compromise with this option than with option 1 since tooth No. 8 would also assist in supporting the pontic for No. 9)

The upsides of this option included:

1. Better prognosis than option 1 since tooth No. 8 would aid compromised tooth No. 10 in supporting missing tooth No. 9

2. This option would provide the best aesthetic outcome

3. With this option, we would have better control over the shape and aesthetics of No. 8

The family was told that if they were interested in this option, our next steps would be to work with my ceramist to complete a diagnostic wax-up to plan the case. Once that step was completed, we would be ready to start. We would prepare the teeth for the restorations and place temporary restorations, which would be indicative of the final result (based on the diagnostic wax-up). Carson would wear these temporary restorations for approximately 6 weeks while the laboratory fabricated the final porcelain restorations. This would give him time to ensure he was pleased with the anticipated final result. The family was advised that the final restorations might have to be returned to the lab for modifications if the shade match was not ideal. In this case, the temporaries would be worn longer than 6 weeks. Once the final restorations were in place, it would also be necessary to make new retainers.

The family was told that this was quite a bit more involved than we had previously discussed (certainly more involved than a Maryland bridge); however, I did not want Carson to continue suffering the consequences of failure of a front tooth any longer at such a critical social and physical developmental time in his life. The previous experience with a Maryland bridge was hard on Carson and the family, and we didn’t want to repeat that experience for him. Again, it was reinforced that this should be more successful than the Maryland bridges that had already failed for Carson. This was a critical time in Carson’s formative years, and I felt he deserved the option of a stable, good-looking smile he could feel confident in.

To be sure all of the options were understood, we did discuss the option of making a removable acrylic partial (flipper). They had no interest in considering this option (and in all honesty, neither did I).

IMPLEMENTING THE PLAN

Ultimately, the family chose the conventional 3-unit bridge from teeth Nos. 8 to 10 and a porcelain veneer for tooth No. 7 for the best symmetry. We whitened Carson’s teeth first using the Zoom! in-office whitening system (Philips Oral Healthcare). We completed the diagnostic wax-up via typical analog PVS impressions and stone models with Treasure Dental Laboratory in Idaho Falls, Idaho. Once the diagnostic wax-up was completed, No. 7 was prepared for a conservative porcelain veneer, and teeth Nos. 8 and 10 were prepared for an all-porcelain bridge using a clear suck-down matrix of the wax-up to ensure prep design supported the planned restorations. Lithium disilicate (IPS e.max [Ivoclar]) porcelain restorations for the case were planned, and the case was temporized using the spot-etch and bond/shrink-wrap technique using a putty matrix of the diagnostic wax-up. (Products used for the temporary restorations included Prime&Bond elect Universal Dental Adhesive [Dentsply Sirona] and Integrity monomethacrylate/polymethacrylate provisional material [Dentsply Sirona] in bleach shade). The challenging part aesthetically was addressing the tipping of tooth No. 10. The contours on the distal of the bridge were not ideal but were the best we felt we could achieve based on the natural tooth position present underneath the bridge. Treasure Dental Laboratory did an amazing job on this case.

Prior to and during treatment, it was noted that Carson’s muscles for smiling (oribicularis oris, risorious, LLSAN, etc) appeared to be somewhat atrophied. We could barely move the lips out of the way to take photos of the preps for the laboratory and when finishing the provisionals. This is the explanation for the less-than-ideal photos seen here of the preps. Note how conservative these preps were, especially theminimally prepared lingual surfaces. There is just a finish line at the gingival aspect of the lingual surfaces and smoothed lingual surfaces to blend them into the preparations. There was no need for substantial lingual preparation because of the patient’s overjet (Figures 13 and 14.)

Figure 13.

Figures 13 and 14. Conventional bridge preps for IPS e.max (Ivoclar) teeth Nos. 8 and 10 and IPS e.max porcelain veneer prep No. 7; the lingual surfaces of Nos. 8 and 10 were minimally prepared since the patient had overjet.

The transformation was immediate. When Carson came in for us to check the provisionals, the hoodie was still there, but you can see in the photos his attempts to smile for the first time in many years (Figure 15). This was definitely the first time we had ever seen even an attempt at a smile from Carson.

Figure 15. Carson wearing his provisionals and still wearing his hoodie but obvi- ously attempting to smile.

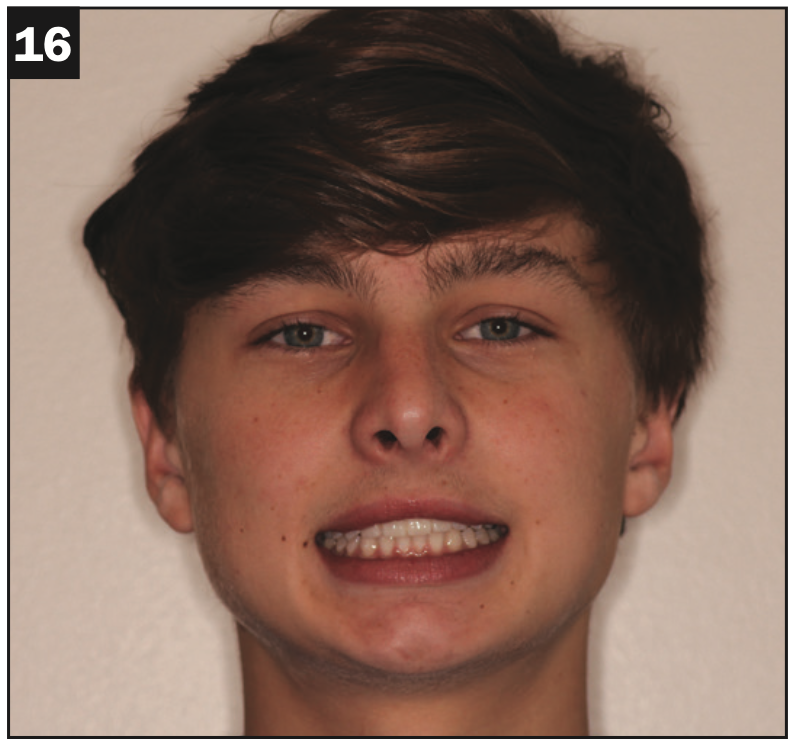

Figure 16.

Figure 17.

Figures 16 to 18. Final IPS e.max restorations: porcelain veneer for tooth No. 7 and a 3-unit bridge for Nos. 8 to 10. Gone is the hoodie, and already Carson is building his atrophied smile muscles.

The completed IPS e.max restorations are seen in Figures 16 to 18. It is notable that the hoodie is gone, and the smile muscles are only growing stronger. In person, he was bubbly to the point of being excited. My reward was the fact that he hugged me instead of barely looking at me and giving me one-word answers. And he told me he had even asked a girl to his upcoming homecoming dance.

FINAL COMMENTS

Was this the hardest case technically? No. Was it super sophisticated? No. Was it the most aesthetic case you’ve ever seen in your professional life? No. Will some dentists comment about doing a 3-unit anterior bridge for a 16-year-old? Yes! But did the treatment provided substantially change a person’s life? Yes! Did seeing his life change for the better change my life for the better? One thousand times, yes!

It is hard sometimes to keep going strong after 20 years at it. Dentistry is hard on many days. Cases like these are what keep me going. I hope you enjoyed reading about it. I encourage us all to “think outside the box” when the Carsons of the world land in our offices—no one wants to do a 3-unit bridge and a veneer in a 16-year-old. But I do believe this was the right answer in this case. I am certain Carson and his family agree. I hope you are inspired to think outside of the box should a Carson ever walk into your office!F

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Hoppe earned her BA in biology with a minor in chemistry from Texas A&M University and her DDS degree from the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston. She was awarded the prestigious Fellowship in the AGD in 2012. Dr. Hoppe owned and operated a small dental practice in Austin, Texas, for 10 years. Upon relocation to Florida, Dr. Hoppe stepped into the role of dental director for the Children’s Volunteer Health Network, treating more than 1,000 children and providing more than $300,000 in free dental care for underprivileged children in Walton and Okaloosa Counties. She simultaneously opened her state-of-the-art comprehensive care dental office, 30A Smiles, which she co-owns in the Inlet Beach area. She can be reached via her Instagram handle, @drlindseyhoppe, or at her website, 30asmiles.com.

Disclosure: Dr. Hoppe reports no disclosures.