According to the concept of a cuspid-protected occlusion, the interlocking relation of the maxillary canines between the mandibular canines and the first premolars is the most important articulation in the natural dentition. In closure of the jaws in mastication, the maxillary canines act as protective stress breakers that absorb the brunt of the muscular forces and guide the mandible so that the posterior teeth come into closure with a minimum of horizontal forces. In lateral and protrusive excursions, the mandibular canines and the first premolars engage the palatal surface of the maxillary canines so as to disocclude the incisors, premolars, and molars, and protect them from undesirable horizontal forces.1

This article presents a case report that illustrates certain oral health problems that can result from a lack of cuspid-protected occlusion, and the treatment performed to resolve those problems.

CASE REPORT

A 56-year-old patient presented with a chief concern of fracture of the lower right second molar, as well as chronic, generalized soreness of the facial gingival tissue in the same area. She stated that 5 years prior, she had periodontal surgery in the form of a distal wedge procedure to correct the defect on tooth No. 31. However, the area relapsed and had been a chronic problem. The distal-buccal cusp of tooth No. 31 had fractured to the level of the gingival margin, and a large occlusal buccal amalgam was present. Additionally, at the time of diagnosis the periodontal measurements were 5 mm distal-facial, 6 mm facial, and 4 mm mesial-facial. Each of the three sites showed moderate bleeding on probing.

|

| Figure 1. Incisal attrition of mandibular anterior teeth. |

The patient’s overall periodontal health was excellent. Home care and plaque control were above average. Comprehensive periodontal charting revealed overall pocket depths of 2 to 3 mm. Tissue texture was stippled, pink, and well attached. All areas showed excellent periodontal health, with the exception of the facial areas of teeth Nos. 18 and 31. Additionally, it was noted that generalized occlusal and incisal attrition was present in both maxillary and mandibular arches (Figure 1).

Examination of the patient’s occlusion revealed a possible etiology for these problems: when she moved into right and left lateral excursions, balancing interferences were apparent on teeth Nos. 18 and 31. She had lost cuspid guidance because of wearing away of tooth structure on both mandibular cuspids. In parafunctional movements, the palatal cusp of the maxillary second molar was in full contact with the occlusal inclines of the distal-buccal cusps of teeth Nos. 18 and 31. In addition, the patient had a bruxism habit and wore a night guard when sleeping and occasionally during the day.

This patient’s teeth, as well as periodontal tissues in isolated areas, were breaking down because of occlusal dysfunction. Because cuspid guidance was lost, the mandibular second molars were subjected to lateral movements, producing excessive wear, fracture of the cusps, and isolated periodontal pocketing.2 When the occlusal forces are excessive or inadequate, the functional component in periodontal disease is unfavorable. The destructive effect of inflammation as it spreads from the gingiva into the supporting tissues is accentuated by the tissue damage from occlusal trauma. Inflammation and trauma from occlusion therefore become codestructive factors in periodontitis. In periodontosis, occlusal forces affect the pattern and severity of bone destruction initiated by noninflammatory degeneration of the periodontal tissues.1

TREATMENT PLAN

Short-term treatment goals were to establish anterior guidance using a rapid, noninvasive, conservative, and relatively inexpensive technique in order to eliminate lateral interferences. With the occlusion idealized and removed as an etiologic factor for the soft tissue condition, it was hoped that site-specific conservative periodontal treatment could eliminate the periodontal pocketing and inflammation seen on teeth Nos. 18 and 31.

With these goals achieved, the long-term treatment plan consisted of a full-mouth reconstruction involving increasing vertical dimension and utilizing all-ceramic restorations to complete the case.

PROCEDURE

In this case, minimal tooth preparation was needed for the mandibular left and right cuspids. No anesthetic was required. A rubber dam was not used because it was necessary to visualize the amount of tooth wear that had taken place, as well as to visualize the entire arch during the placement and sculpting process. The preparations were beveled about 3 mm from the cusp tip with a diamond (Brasseler No. 5850-016). The dentin was also roughened to enhance the bonding process and the area was etched for 15 seconds with UltraEtch (Ultradent), followed by placement of Excite (Ivoclar Vivadent) adhesive to properly plasticize the dentin.

|

|

| Figure 2. Completed restoration of cuspid to re-establish normal contour. | Figure 3. Completed restoration of cuspid provides anterior guidance and disclusion of posterior teeth. |

The composite resin was Esthet-X (DENTSPLY Caulk). This microhybrid is easy to manipulate and place, and shows almost no slump. We chose A3-3 Body and YE translucent for the shade (Figure 2). After placement, the occlusion was adjusted in centric and excursive movements. Cuspid guidance had been re-established, and balancing and working contacts were eliminated. The restorations were finished and polished with Flexidisc (Cosmedent), Enhance (Cosmedent), and a Jiffy brush (Vitradent) (Figure 3).

With the occlusal component of cuspid guidance satisfied, periodontal therapy was initiated. The patient was anesthetized and the facial periodontal pocket on tooth No. 31 was debrided with hand instruments and micro-ultrasonics. It was noted that there was heavy bleeding on scaling. One of the objectives of periodontal therapy is to establish a root surface that is biologically acceptable to the healing of the adjacent soft tissue. Ultrasonic instruments can be utilized because they efficiently remove sub- and supra-gingival calculus and are less likely to produce root damage. Also, they are kinder to enamel and soft tissue, can utilize proper irrigation with water or chlorhexidine, and help with bacterial decontamination by disrupting the bacterial cell wall through ultrasonic activity.3 Using acoustic energy scalers for debridement bridges the gap between gross scaling and fine scaling. The thin tips available for these instruments allow easy access into the deepest pockets, as well as thorough debridement. Clinicians who are highly skilled with curettes can transfer their expertise to ultrasonic scalers and effectively debride periodontal pockets in less time and with added patient comfort. The ultrasonic used in this case was DENTSPLY’s DualSelect unit.4

The irrigation solution used was Consepsis (Ultradent), a form of chlorhexidine. Recent studies have consistently suggested that chlorhexidine irrigation enhances the reduction of gingival inflammation. Also, these studies have noted reduced plaque and gingival scores of bacteria, and have shown that irrigation with medicaments consistently improved the clinical and microbiologic parameters and tend to outperform irrigation with water alone.5

Following chlorhexidine irrigation, the area was lased with a DioLase ST diode laser (American Dental Technologies) on a pulse setting of 0.4. The diode laser is used as a supplemental treatment aimed at reducing or eliminating bacteria, inactivating bacterial toxins, and removing diseased epithelial lining, but it does not contribute to calculus removal.6 The Diode laser therapy, in combination with scaling and micro-ultrasonics, supports healing of the periodontal pockets through elimination of bacteria.7 Studies on diode-laser treatment have yielded very favorable results regarding the bacterial reduction of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Prevotella intermedia.8

At the patient’s 6-week appointment, the facial periodontal pocket of tooth No. 31 was measured at 4 mm. Very light bleeding was noted on probing and sweeping of the sulcus. Inflammation had been greatly reduced, and nonsurgical pocket reduction with reattachment had taken place. The entire quadrant was then retreated with micro-ultrasonics, hand instrumentation, and diode lasing, again on a pulse setting.

RESULTS

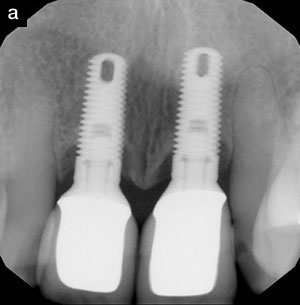

|

|

| Figure 4. Completed full reconstruction. | Figure 5. Excellent periodontal health has been achieved. |

Tissue re-evaluation was performed approximately 9 months after the initial nonsurgical periodontal therapy with comprehensive full- mouth periodontal charting. Pocket measurements for teeth Nos. 18 and 31 were reduced to 2 to 3 mm, and tissue was pink, firm, and stippled. There was no bleeding on probing. The composite restorations on teeth Nos. 22 and 27 were functioning well and were aesthetically acceptable. The next step of full reconstruction was finalized. Figures 4 and 5 show the completed case and the excellent periodontal health.

DISCUSSION

The identity that my team and I want for our practice is one of dedication to excellence. Our method to achieve this identity is to offer each patient customized, comprehensive, state-of-the-art care. This includes complete and accurate periodontal diagnosis and treatment planning with the ultimate goal of perfect tissue. The benefit of this for our patients is that they have active participation in selecting the level of care that is best for them, that is, to restore their mouths to comfort, health, aesthetics, and function.

Acknowledgment

This article incorporates both conservative, nonsurgical periodontics as taught by JP Consultants Institute, with occlusal and restorative principles taught by Dr. Ronald D. Jackson and Dr. William Dickerson at the Las Vegas Institute for Advanced Dental Studies.

References

1. Glickman I. Trauma from occlusion and the etiology of periodontal disease. Principles of occlusion. In: Clinical Periodontology. 1969;296 and 701-705.

2. Jackson R. Loss of cuspid guidance: a functional and aesthetic dilemma. Dent Today. 2000;7:56-61.

3. O’Hehir T. Periodontal debridement therapy. RDH Magazine. 1995;6:49-52.

4. Bussac G. Periodontal disease: part II- treatment strategies. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1999;11:216-218,220,222.

5. Rethman M, Greenstein G. Oral irrigation in the treatment of periodontal disease. Curr Opin Periodontol. 1994;99-110.

6. Moritz A, Schoop U, Goharkhay K, et al. Treatment of periodontal pockets with a diode laser. Paper presented at the Department of Conservative Dentistry, Dental School of the University of Vienna; 1998.

7. Gold S, Valardi M. Effect of Nd: YAG laser curettage on gingival crevicular tissues. J Dent Res. 1992;71:299 (abstract 1949).

8. Renvert S, Wikstrom M, Dahlen G, et al. Effect of root debridement on the elimination of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Bacteroides gingivalis from periodontal pockets. J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17:345-350.

Dr. Reichwage maintains a private practice in Fort Wayne, Ind. He holds program certifications from the Las Vegas Institute for Advanced Dental Studies, Pacific Esthetic Continuum, Academy of Laser Dentistry, JP Consultants Institute, and Dr. James Carlson. Dr. Reichwage is a member of the Academy of Operative Dentistry, Academy of Laser Dentistry, ADA, Indiana Dental Association, and Isaac Knapp District Dental Society. He has served organized dentistry on both state and local levels and is a past president of the Isaac Knapp District.

Dr. Rydesky has been practicing dentistry in Mechanicsburg, Pa for over 30 years. He has numerous postgraduate courses to his credit including his latest interest, cosmetic dentistry, and teaches with Drs. William Dickerson, Ron Jackson, and Newton Fahl at The Las Vegas Institute. In addition, he gives clinical presentations at his private practice demonstrating the use of the surgical diode laser, and his office has recently become a teaching chapter of the Institute.