Root resorption (RR) is the progressive loss of dentin and cementum by the action of odontoclasts.1 RR may occur as a physiologic or pathologic phenomenon, and it presents in many different forms.

There is external root resorption2 (ERR) appearing initially on the side of the root, for example:

- Cervical, meaning it is limited to the cemental-enamel junction

- Localized, meaning it is limited to the coronal-middle or apical third of the root

- Generalized, meaning it may affect more than one-third of the root surface

- Inflammatory. Though RR is usually inflammatory, a less common version is replacement resorption, wherein the resorbed tooth structure is replaced by bone—known more commonly as ankylosis and abbreviated to RER (replacement external resorption).

There is also internal root resorption (IRR) appearing initially within the root canal, for example:

- Localized, meaning it may be noticed any third of the root or crown, or even

- Generalized, affecting more than a third of the root canal surface.

RR may occur in any third of the root, or it may even affect the whole root. It is important to discern if RR is ERR or IRR; this is because an incorrect diagnosis may lead to an inappropriate treatment plan. The most common identifiable etiology for RR is trauma. How can we tell if the RR is internal or external?3 Usually with 2 periapical images, where the only difference in the second image is a 10° to 15° change of the horizontal angulation. If the RR “moved” in the second image, then the clinician would know the RR is external; however, if the RR seems to remain in the same place in the second image, the clinician would know it’s IRR. Another approach is to prepare a limited CBCT image, which is usually quite enough to see if the RR is internal or external.

|

What Causes Adult Root Resorption?

ERR affects the surface of the root and is a common sequel to dental luxation and avulsion injuries. ERR can advance rapidly, such that an entire root surface may be resorbed within just a few months if left untreated. ERR also affects teeth with chronic apical periodontitis.4 One of the most common causes for apical RR is overzealous orthodontic tooth movement.3,5 In fact, if orthodontic pressures are much too strong for the body to endure, it may trigger a rapid generalized RR both internally and externally.6 Other causes of oral trauma leading to RR include athletic injuries, fighting, automobile accidents, etc.

Regarding RER (ankylosis), its clinical presentation is quite unique. For example, when the tooth is percussed with the handle of a mouth mirror, it will offer a high-pitched metallic sound. When imaged radiographically, three-fourths of the root could be replaced by bone, and the crown will present as quite stable when the clinician attempts to check for mobility. Even when most of the root has been replaced by bone, it’s not uncommon for a tooth to stabilize (ie, bone replacement has stopped) and remain functioning well for many years!

Beyond trauma, there are other causes for RR, including overheating a tooth during internal bleaching of a crown, replantation of avulsed teeth, chemotherapy for certain cancer patients, etc.

Repairing Root Resorption

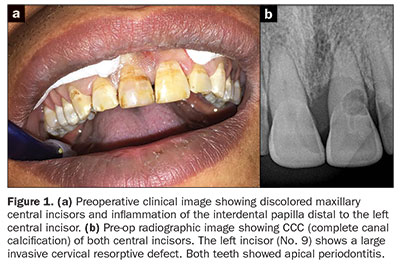

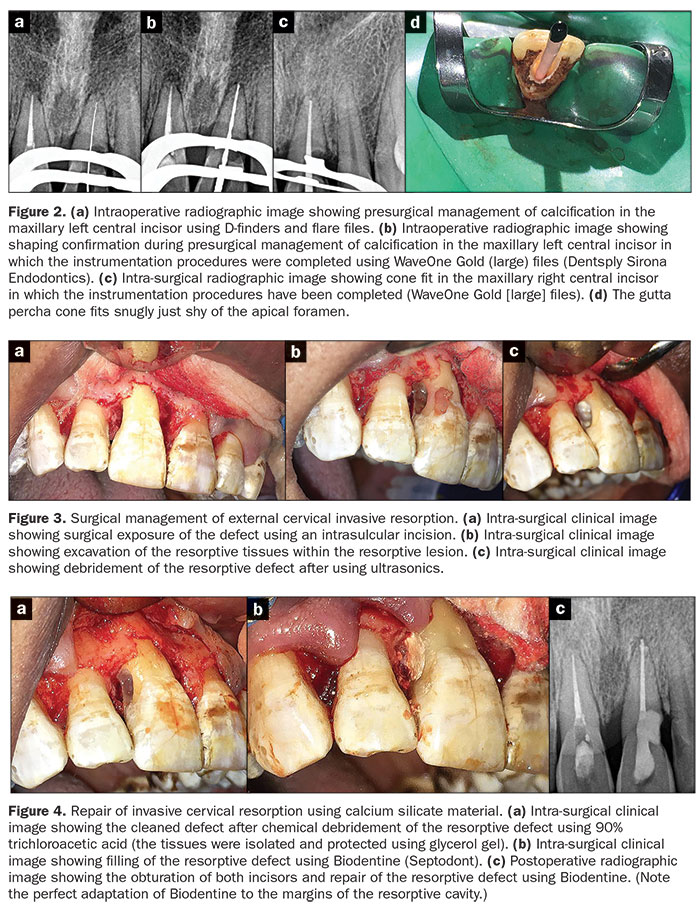

Studies have shown that calcium silicates are quite successful in arresting RR.7 For example, in cases where the resorptive defect can be accessed directly (such as the cervical external RR in Figure 1), the clinician should mix Biodentine (Septodont) and carry it to the resorptive defect with an amalgam carrier. The setting Biodentine can be carved in a few minutes because initial setting occurs approximately 10 to 12 minutes after mixing (the setting time is partly affected by ambient temperature and humidity) (Figures 2 to 4). The ease of handling and the biocompatible quality of the calcium silicate-based Biodentine make it a good restorative material for RR. Long-term followups show Biodentine remains stable.7,8

|

Whenever there is an athletic injury or an automobile or bicycle accident involving oral trauma—or even aggressive orthodontic treatment—the prudent practitioner should have a heightened “index of suspicion” that RR might occur. Thus, after carefully recording responses to all clinical testing (eg, radiographs, percussion, palpation, mobility, response to thermal stimulation, electric pulp testing, coronal discoloration, and periodontal probing), have the patient return 2 weeks later and repeat the testing. If the test findings 2 weeks later are like the first findings, then have the patient return in 6 weeks and compare the findings to the initial testing. If there is no evident change in the responses to the testing, then the patient should return for follow-up testing every 3 to 4 months for at least 2 years.

Clinicians are urged to keep all radiographic images and test findings for at least 5 years. In this digital era, this should not be a problem. Later, the patient may request access to this data. Furthermore, years later, some aggressive attorneys may attempt to show how the clinician made some poor decisions; thus, preserving this data is the best protection for the prudent practitioner.

References

- Trope M. Root resorption due to dental trauma. Endod Topics. 2002;1:79-100.

- Patel S, Kanagasingam S, Pitt Ford T. External cervical resorption: a review. J Endod. 2009;35:616-625.

- Levin L, Trope M. Root resorption. In: Hargreaves KM, Goodis HE, Tay F, eds. Seltzer and Bender’s Dental Pulp. Quintessence Publishing; 2002.

- Laux M, Abbott PV, Pajarola G, et al. Apical inflammatory root resorption: a correlative radiographic and histological assessment. Int Endod J. 2000;33:483-493.

- Tronstad L. Root resorption: etiology, terminology and clinical manifestations. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1988;4:241-252.

- Nair MK, Levin MD, Nair UP. Radiographic interpretation. In: Hargreaves KM, Berman LH, eds. Cohen’s Pathways of the Pulp. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2016:33-70.

- Camilleri J. Investigation of Biodentine as dentine replacement material. J Dent. 2013;41:600-610.

- Berman L, Blanco L, Cohen S. A Clinical Guide to Dental Traumatology. Elsevier; 2007:1-10.

Dr. Cohen is a Diplomate of the American Board of Endodontics. He lectures worldwide on endodontics and is the senior editor for all 9 editions of the definitive endodontics textbook Pathways of the Pulp and a co-editor of the renamed tenth edition, Cohen’s Pathways of the Pulp. After completing his studies in the Endodontics Postgraduate Program at the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Cohen began his private practice in San Francisco. Dr. Cohen served as the Chairman of the Endodontic Department of the University of the Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry in San Francisco and has continued his long relationship with the school as an adjunct clinical professor of endodontics. He can be reached at scohen@cohenendodontics.com.

Dr. Shawky received his BDS from Cairo University. He is a micro-endodontic consultant in private practice in greater Cairo, Egypt and lectures extensively nationally as well as internationally. His academic field of research is regenerative endodontics, in which he published and is currently publishing laboratory and clinical studies. He is currently an OPL in Dentsply Sirona MENA. He has conducted more than 25 CE certified endodontic trainings both nationally and internationally. He is currently a lecturer in the department of endodontics, Cairo University. He can be reached at drahmedshwky@gmail.com.

Disclosure: The authors report no disclosures.

Related Articles

A Modern Approach to Post and Core Restoration: An Evolving Paradigm

Ortho-Aesthetics: One Solution to External Resorption

Grant to Explore Use of Biomarkers in Detecting Dental Resorption