Oral cancer represents the sixth most common malignancy worldwide, with an estimated 450,000 new cases diagnosed annually.1Approximately 90% of oral cancer diagnoses are squamous cell carcinoma.2

In the United States, an estimated 53,000 individuals will be diagnosed with oral cancer, and of those, almost 10,000 will succumb to their disease.1Despite the overall advances in diagnostic and surgical techniques, the five-year survival rate remains only slightly greater than 50%.1

All members of the dental care team, including hygienists, assistants, general dentists, and specialists, play an important role in the detection and treatment of oral cancer. In addition, patient education is a critical part of the management process. This article will discuss current trends in oral cancer and dispel common misconceptions related to the disease.

FACT: Prevention and Early Detection Are the Best Methods in Treating Oral Cancer

There has been a well-documented association between increased mortality rate of oral squamous cell carcinoma and the stage at which it is detected. Higher-stage oral cancer (stage III and IV) has a significantly worse prognosis than its lower-stage counterparts (stage I and II).2Oral cancer is staged via the TNM classification system, where T refers to tumor size, N refers to nodal involvement, and M refers to metastases elsewhere in the body.

Patients with a newly diagnosed oral malignancy should undergo an appropriate full-body imaging study to determine the presence of metastatic involvement elsewhere. Tumor spread to lymph nodes represents the single most important prognostic marker, and lymph node positivity is associated with a poorer prognosis.2

FICTION: HPV Frequently Causes Oral Cancer (Involving the Lateral Tongue, Floor of Mouth)

A cursory search will provide an almost overwhelming amount of information on the relationship between human papillomavirus (HPV) and oral cancer. However, the facts and figures cited can be misleading.

|

|

|

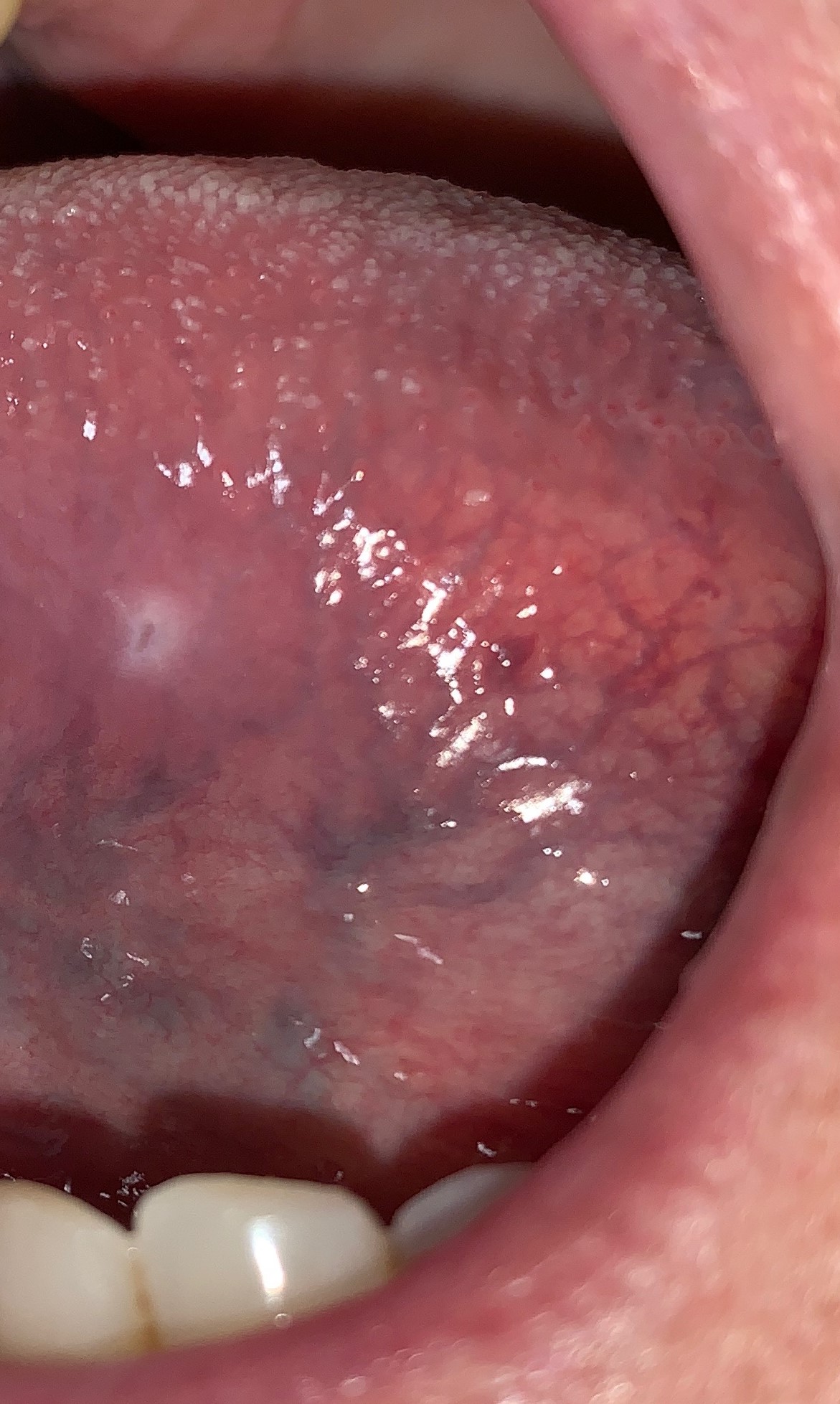

Figure 1: Clinical photographs of oral leukoplakias. Panel A showed benign epithelial hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis when biopsied. Panel B showed moderate epithelial dysplasia. The distinction between benign and (pre)malignant cannot be made based on clinical appearance alone. |

When describing “oral cancer,” it is most appropriate to subdivide cases as either anterior oral cavity or oropharyngeal. The vast majority of cases of HPV-associated cancer are oropharyngeal in origin, meaning they involve sites such as the base of the tongue and the tonsils.3

Alcohol and tobacco use, the historical risk factors of conventional oral squamous cell carcinoma, remain the most common causes of anterior oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma.The lateral tongue and the floor of mouth also still are the sites where oral cancer is most likely to develop.

The emerging role of HPV in oropharyngeal cancer should not be downplayed, though. If a patient presents with complaints such as persistent sore throat, dysphagia, or odynophagia, a referral to an ear, nose, and throat physician would be prudent.

FACT: A Leukoplakia Is Considered a Premalignant Condition

A leukoplakia, by definition, is a white patch or plaque that has persisted for at least two weeks, cannot be removed, and cannot be identified as any other specific disease. Also, a leukoplakia is a clinical diagnosis only and may represent oral premalignancy (dysplasia). In some large studies, approximately 5% to 20% of all clinical leukoplakias showed microscopic evidence of dysplasia.3

The reason all leukoplakias are considered premalignant conditions even though approximately only a quarter of them show evidence of dysplasia is because there is no way to clinically determine with absolute certainty which leukoplakic lesions are premalignant (dysplasia) or malignant (invasive squamous cell carcinoma) and which are benign (epithelial hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, ie, frictional keratosis) (Figure 1). Therefore, a biopsy is recommended for all leukoplakic lesions to determine their etiology.

FICTION: It’s Possible to Determine Which Oral Premalignant (Dysplastic) Lesions Will Progress to Invasive Cancer

Oral dysplasias are graded as mild, moderate, or severe based on how much of the epithelium is affected. Changes limited to the basal (bottom) third of the epithelium are diagnosed as mild. Those involving the basal half are moderate. And, those with changes extending to the upper third are severe. Full thickness involvement of the epithelium is referred to as carcinoma in situ.

|

|

|

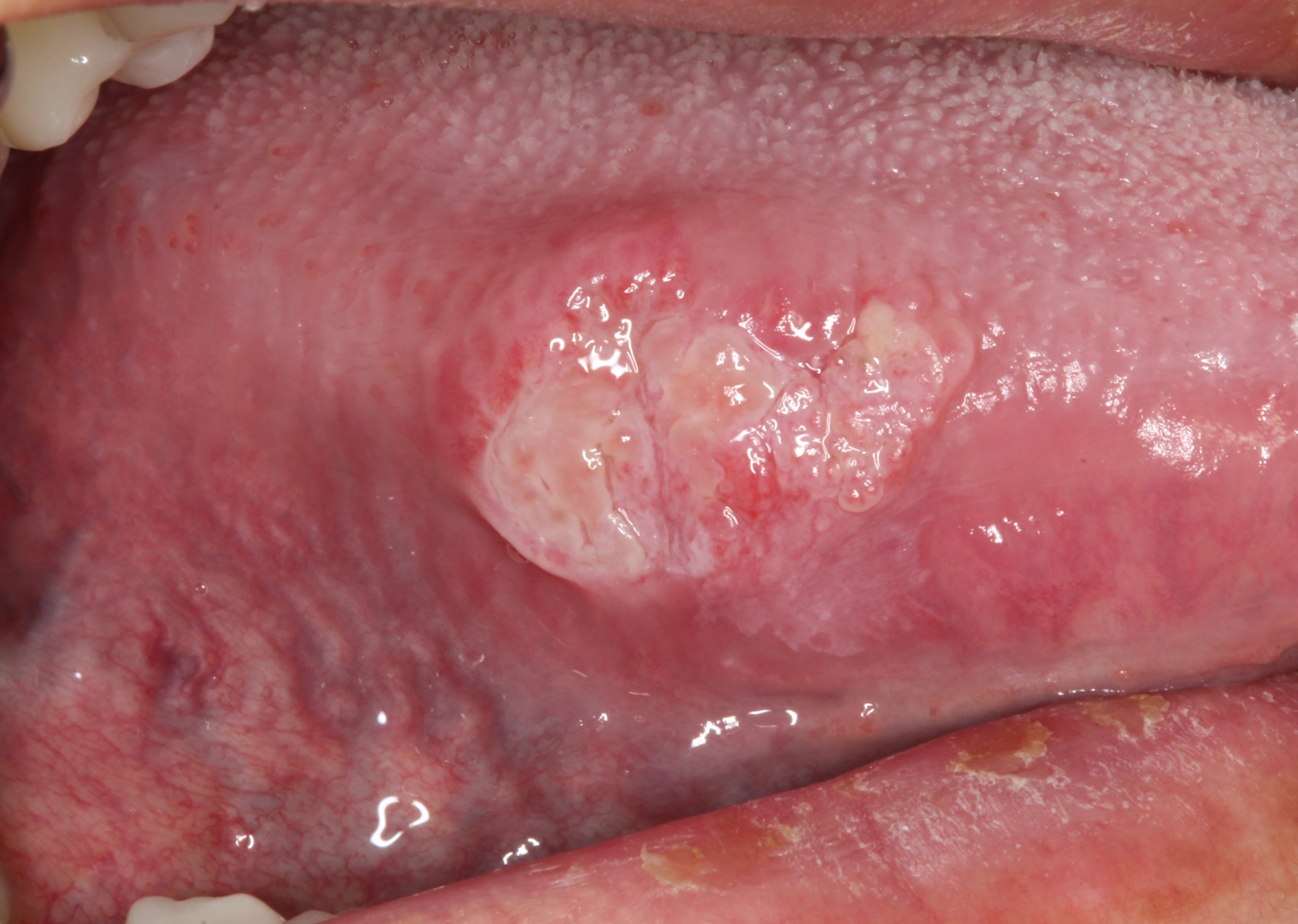

| Figure 2: Some of the varied appearances of oral cancer. Panel A shows an indurated, focally ulcerated swelling of the right lateral tongue. Panel B shows a lesion with both an exophytic and an ulcerated component arising from an erythroleukoplakia of the left lateral tongue. Panel C shows oral cancer mimicking an inflammatory gingival lesion. (Panel A courtesy of Dr. David Moisa, Panel B courtesy of Dr. Garrick Alex) |

Generally speaking, the more significant the degree of dysplasia, the higher the risk of transformation to invasive carcinoma. However, there is currently no way to determine which oral dysplasias are more likely to undergo malignant transformation or progress from a lower grade to a higher one. Furthermore, some dysplastic lesions that are mild or moderate may become invasive in a phenomenon known as drop-off carcinoma.4

Therefore, a diagnosis of mild dysplasia does not necessarily preclude future risk of malignant transformation or even convey a “safer” status as opposed to a severe dysplasia diagnosis. Because of the risk of malignant transformation, and the inability to reliably predict which ones will become worse over time, the current recommendation is complete excision, when feasible, of any oral dysplastic lesion.

FACT: Oral Cancer Can Have Varying Clinical Presentations

In addition to the leukoplakic lesions described above, oral malignancy may also take several other forms (Figure 2). An erythroplakia describes a flat red lesion that, similar to a leukoplakia, has been present for at least two weeks and cannot be removed or identified as any other disease.

Unlike leukoplakias, the overwhelming majority of erythroplakias show either severe dysplasia or invasive carcinoma on biopsy. An erythroleukoplakia, or “speckled leukoplakia,” is a mixed red and white lesion that also often shows higher grades of dysplasia on biopsy.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma should also be included on the differential diagnosis for a persistent ulceration. It can mimic “granulation tissue” seen in poorly healing extraction sockets. When it involves the gingiva, it may resemble more commonly encountered inflammatory lesions such as pyogenic granuloma.

FICTION: A Brush Biopsy Can Be Used to Diagnose Oral Cancer

A brush biopsy is a cytologic examination, rather than a histologic one. It will only be able to assess whether cellular atypia is observed, but cannot evaluate for tumor invasion or degree of dysplasia, as these features rely on interpretation of tissue architecture.

As such, a brush biopsy is of poor diagnostic value, and its use should be discouraged. If you are concerned about the appearance of an oral lesion, a standard tissue biopsy, performed with a scalpel, is the gold standard for diagnosis.

FACT: A Person with a Known History of Oral Dysplasia or Malignancy Is More Prone to Develop Additional New Primary Lesions

This relates to the concept of field cancerization, which states that areas of cells in the tissue nearby a dyplastic or malignant lesion may also be affected by carcinogenic alterations.1

Even though these sites may look clinically normal, they are at increased risk of undergoing malignant change in the future. For this reason, excision of any clinical lesion with clear (negative) margins is always recommended, as is close, long-term clinical follow-up, even after a lesion has been completely excised.

FICTION: Oral Cancerous Lesions Are Frequently Painful

Many oral precancerous and cancerous lesions are initially asymptomatic. As a result, patients may be unaware of their presence. A thorough oral evaluation is needed to identify these lesions. In later stages, when the tumor starts to involve neural structures (a process called perineural invasion), pain may be a presenting feature.

FACT: The Optimal Treatment Modality for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Is Surgical Excision

Surgical excision is the preferred method of treatment for oral cancer. Radiation and/or chemotherapy are reserved for those patients who are not surgical candidates, or cases where the surgical margins are either positive for tumor or dysplasia.

FACT AND FICTION: Diagnostic Screening Tools Are Useful in Detecting Oral Cancer

Diagnostic screening tools were designed to assist providers with the detection of possible oral premalignant and malignant lesions. These aids are not always reliable, however, and may produce both false positives and negatives.

My personal opinion is that the best screening tools that you have are your eyes and your hands. Performing a thorough extraoral and intraoral examination as well as assessing any identified lesion for its color and texture can provide significantly more valuable information than any screening test. That being said, if these ancillary tests help promote provider awareness, then they may be of some value.

We have made significant progress as a field in our ability to treat and detect oral cancer. Despite this, the five-year survival rate remains quite low. With both continued research and astute clinicians, it is my hope that we will see continued improvement in the years to come.

References

- El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ. WHO classification of head and neck tumours4th Lyon: IARC, 2017.

- Muller S. Update from the 4thedition of the world health organization of head and neck tumours: Tumours of the oral cavity and mobile tongue. Head Neck Pathol2017; 11(1): 33-40.

- Carrard VC, van der Waal I. A clinical diagnosis of oral leukoplakia; a guide for dentists. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal2018; 23(1): e59-64.

- Wenig BM. Squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: dysplasia and select variants.Mod Pathol2017; 30:S112-8.

Dr. Peters is an assistant professor of oral and maxillofacial pathology at Columbia University Medical Center, College of Dental Medicine. He received his DDS from Columbia University and completed his postgraduate training in oral and maxillofacial pathology at Columbia University/New York Presbyterian Hospital. He is a diplomate of the American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, a fellow of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, and the recipient of the Academy’s prestigious William G. Shafer Award. Dr. Peters has published in numerous journals as well. He also serves as an adjunct assistant professor of oral histology at the Rutgers School of Dental Medicine. He can be reached at smp2140@cumc.columbia.edu.

Related Articles

Blood Test Detects Presence and Location of Wide Range of Cancers

Preoperative Immunotherapy Triggers Encouraging Response in Oral Cancers

Botanical Drug Shows Effectiveness Against Head and Neck Cancers