INTRODUCTION

Guided surgical procedures allow the practitioner to diagnose and treatment plan dental implant positioning. Being able to visualize the final process prior to any surgical intervention is an art that is accelerated with virtual design. CBCT and software analysis provides a 3D image of the edentulous space that requires a dental implant. Digital positioning helps minimize the fear of damaging vital anatomy, such as the mandibular or mental nerves, and aids in proper angulation in the available hard tissue to maximize the emergence profile and smile design of the final prosthesis. Taking a tooth-down approach to surgical implant placement helps to idealize the final prosthetic design to a high level.

CBCT analysis and subsequent surgical guide fabrication are an outstanding means to a functional and aesthetic end. However, surgical guides are only as accurate as the fabrication process, and any discrepancy or error in fabrication could lead to malposition and possible trauma.

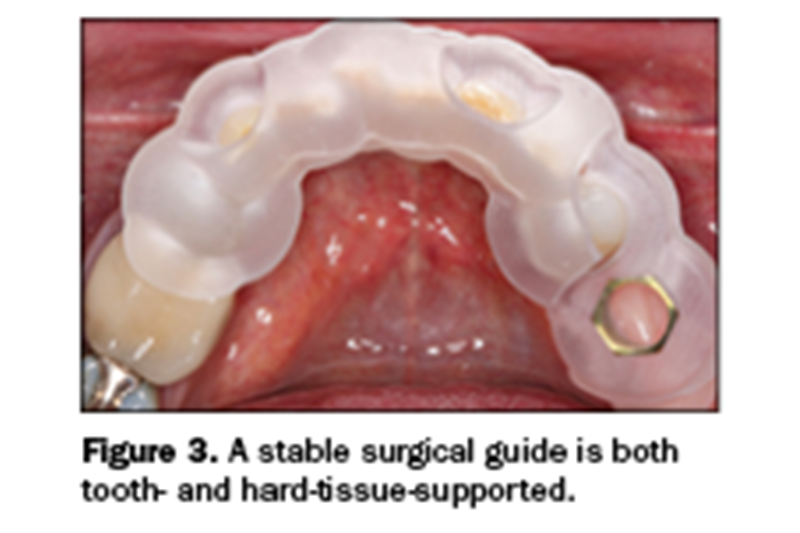

That being said, when the proper high-quality CBCT analysis is done and the surgical guide is both tooth- and hard-tissue-supported, the surgical placement of the implant is precise. It should provide for an outstanding long-term prognosis.

Here we demonstrate the CBCT analysis and fabrication of a tooth-borne surgical guide for the placement of a single dental implant in the edentulous mandibular left first molar to help provide a patient with increased chewing efficiency and function. This single dental implant crown will eliminate the need for the conventional removable partial denture that has been worn. The patient’s quality of life is thus improved.

Several important indications need to be considered before treatment planning any dental implant reconstruction, whether it be a single tooth; multiple teeth; support for a removable, implant-retained palateless overdenture or partial denture; or a fixed full-arch, implant-retained prosthesis.

There are several conditions that must be evaluated. First, the patient’s overall health should be considered. Any healing problems or uncontrolled medical conditions, such as uncontrolled diabetes or immunosuppressive diseases, could affect the integration of the implant.1,2 Medication use, such as bisphosphonates, could inhibit proper healing of bone around the implant.3 Bleeding conditions may be a contraindication to surgical intervention.2 The quantity and quality of available hard tissue must be considered.

There must be adequate vertical and horizontal bone to support the fixture. This means that there should be considerable width to allow at least 1 to 2 mm of facial and lingual cortical bone and enough height to provide an implant that can support an implant crown with at least a 1:1 crown/root ratio.4 The posterior mandible presents some unique complications to both the experienced and unexperienced practitioner. As teeth are lost, the residual ridge will physiologically shrink in 2 dimensions: apically and lingually.

Thus, the implant may not necessarily be placed where the tooth structure was originally; rather, it will be positioned more lingually.5 This must be examined and communicated to the patient because the final crown may feel “thicker” to the patient on the lingual aspect. It is best to discuss the final design with our patients prior to beginning the process. Our patients, however, often present with much information gathered from their internet searches on the benefits of implant dentistry.

Risks need to be explained in detail, especially in compromised circumstances. The maxillary posterior region also provides some complications as teeth are lost. Not only does the residual ridge shrink palatally and apically, but the sinus floor may collapse as the tooth root structure no longer supports it.6

CASE REPORT

CBCT analysis allows the practitioner to evaluate the anatomic restrictions to a high level. Virtual placement and crown fabrication was completed and discussed with the patient (coDiagnostiX [Dental Wings]). Figure 1 illustrates the amount of vertical and horizontal bone loss the patient exhibited, as well as the super-eruption of the opposing dentition. After anatomic and financial considerations were discussed, the patient elected to have a single implant crown placed to improve chewing ability and eliminate the removable appliance he or she had been wearing for years. Epithelial attachment should also be considered here, as there must be an adequate band of attached gingiva on the facial aspect of any dental implant.

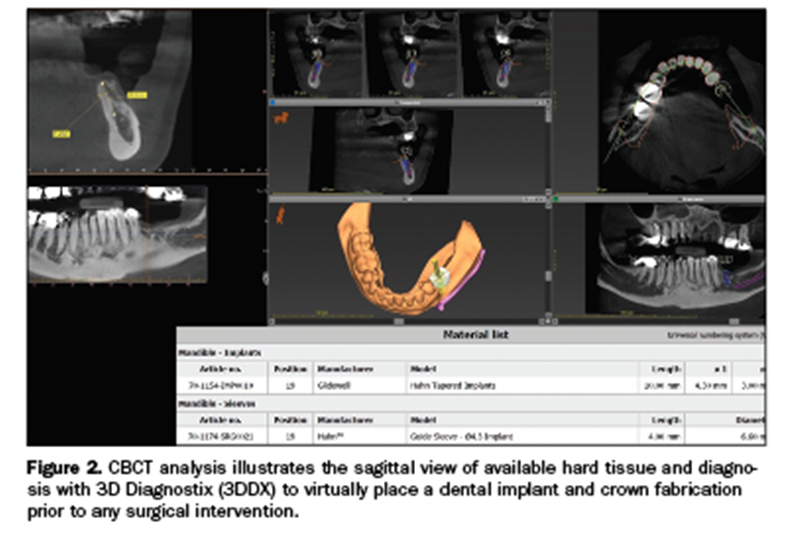

As teeth are lost and bone shrinkage occurs, the mucosal tissue often migrates to the facial aspect of the edentulous ridge.7,8 This concept will be reintroduced shortly. Figure 2 demonstrates the sagittal view of available bone in the mandibular first molar site. Minimal hard-tissue availability and the proximity to the mental foramen and mandibular nerve made this a good situation to consider a guided surgical procedure (PaX-i3D Green [Vatech America]).

As teeth are lost and bone shrinkage occurs, the mucosal tissue often migrates to the facial aspect of the edentulous ridge.7,8 This concept will be reintroduced shortly. Figure 2 demonstrates the sagittal view of available bone in the mandibular first molar site. Minimal hard-tissue availability and the proximity to the mental foramen and mandibular nerve made this a good situation to consider a guided surgical procedure (PaX-i3D Green [Vatech America]).

The implant could be virtually positioned in the available bone, and the final implant-screw-retained crown could be visualized. The access hole for this crown would necessarily be on the lingual aspect of the occlusal surface due to the lingual positioning of the fixture itself. With the information presented via the CBCT scan and accurate study casts, 3D Diagnostix (3DDX) was able to fabricate a stable tooth and a hard-tissue-supported surgical guide to aid my surgical angulation and depth positioning of a 4.3-mm × 10-mm Hahn Tapered Implant System (Glidewell) (Figure 3). The access hole in the surgical guide allowed me to use the Hahn Tapered Implant Guides Surgical Kit protocol during placement.

There are no keys in this system, instead, there are burs that accommodate for the implant itself, soft tissue, and thickness of the guide. This particular system is simple to use and mimics the conventional Hahn surgical protocol. Many of our surgical guides were tissue-supported in the past, which resulted in potential errors in seating. Today, most guides are hard-tissue-supported, which requires a reflection of the tissue to be made so that the acrylic sits directly on the available bone structure.5

Figure 4 illustrates a full-thickness incision on the crestal aspect of the residual ridge in the attempt to save the available attached gingiva.

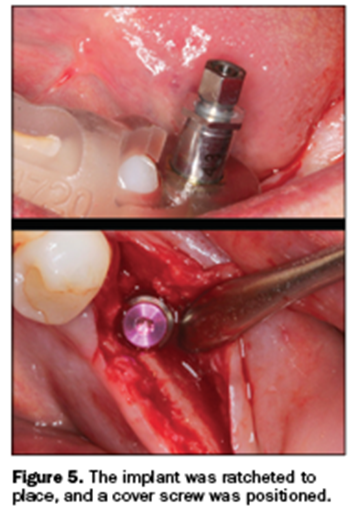

The osteotomy was made directly through the surgical guide. Each osteotomy bur has a stop on it, so keys are no longer required. This concept provides for accurate location. Once the site was prepared, the implant was ratcheted to position, again to the preset hub of the delivery insertion (Figure 5).

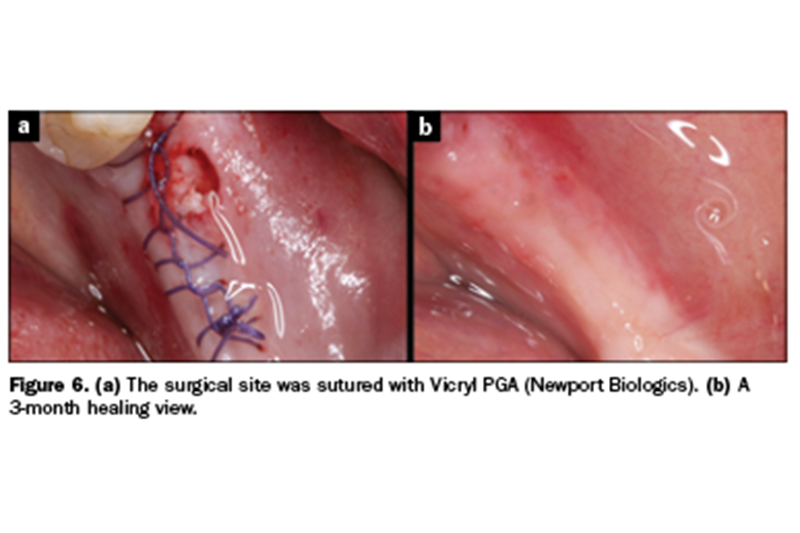

The 4.3-mm-diameter Hahn Tapered Implant System was torqued in the site that was virtually determined by our CBCT analysis and planning software. The Hahn Tapered Implant System has an aggressive thread design and a 1-mm machined collar. A cover screw was hand tightened into the implant, and the tissue was sutured with Vicryl PGA (Newport Biologics) (Figure 6). You can see that the incision line was lingual, but the implant was placed in the available bone.

Following 3 months of integration, the edentulous ridge was healed and ready for the next steps. The implant needed to be exposed to remove the cover screw to thread in an impression coping. Using the surgical guide, an indelible marker indicated the precise implant position.

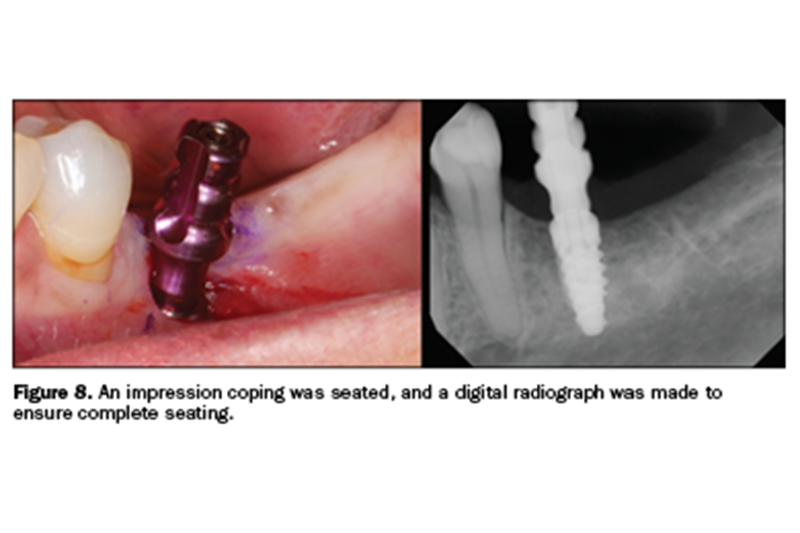

A tissue punch (Salvin Dental Specialties) was used to remove the tissue above the implant (Figure 7). A Hahn Tapered Implant System impression post was threaded into the implant, and a radiograph was taken to ensure complete seating of the metal-to-metal components (Figure 8).

It is critical to realize that there must be keratinized tissue on the facial aspect of all our dental implants.

It is critical to realize that there must be keratinized tissue on the facial aspect of all our dental implants.

Failure to realize this may result in periodontal issues and potential implant failure.

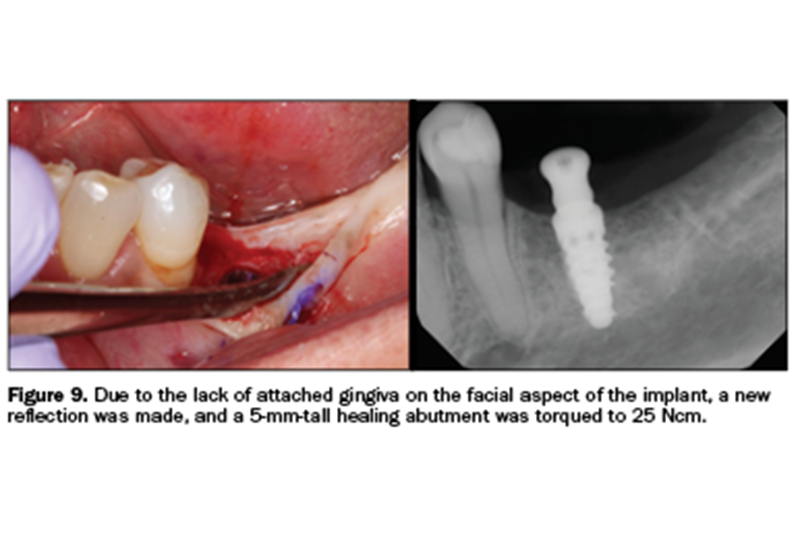

This is where complications may arise. It is clear in Figure 8 that there was no band of attached gingiva on the facial aspect of the impression coping. This would become a problem if not addressed. Even though the impression was made using polyvinylsiloxane medium- and heavy-body material (Kettenbach LP), I decided to do a tissue-repositioning reflection. Again, I made my incision lingual to the crest of the ridge in the hopes of harvesting at least 2 mm of attached gingiva.

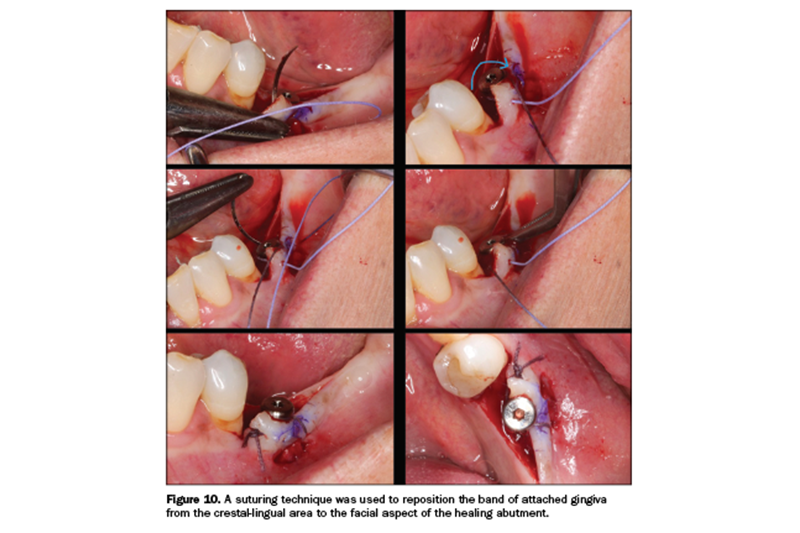

This attached epithelium would then be replaced to the facial aspect of the implant. To do this, a 5-mm-tall healing abutment was torqued to 25 Ncm (Figure 9). A periodontal repositioning technique was used. Figure 10 demonstrates the suturing technique used to reposition the attached gingiva to obtain a healthy band on the facial aspect. The reverse cutting one-half round needle engaged the mesial-facial aspect of the repositioned flap. The suture was then wrapped around the tall healing abutment, not engaging the lingual tissue whatsoever.

The needle was then reversed and engaged the distal-facial aspect. The suture wrapped around the healing abutment again, and a knot was made on the mesial. This took the band of attached gingiva that was originally on the lingual aspect of the crest and moved it to the facial aspect of the implant itself. One suture provided this. The exposed hard tissue would granulate in at a rate of 0.5 to 1 mm per day and require no special care.9-12 There was minimal postoperative discomfort for the patient with this procedure.

The needle was then reversed and engaged the distal-facial aspect. The suture wrapped around the healing abutment again, and a knot was made on the mesial. This took the band of attached gingiva that was originally on the lingual aspect of the crest and moved it to the facial aspect of the implant itself. One suture provided this. The exposed hard tissue would granulate in at a rate of 0.5 to 1 mm per day and require no special care.9-12 There was minimal postoperative discomfort for the patient with this procedure.

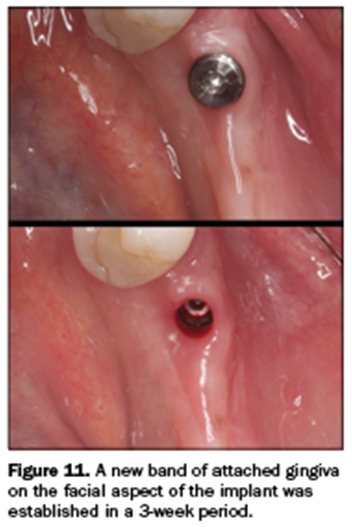

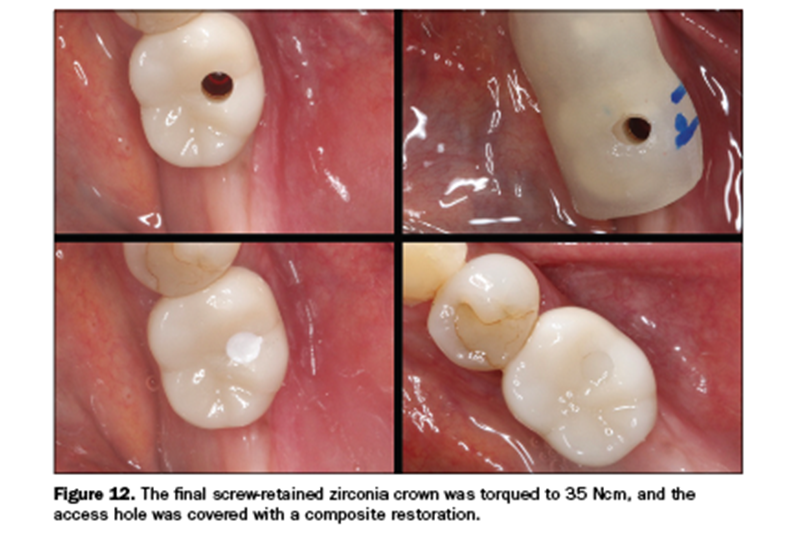

In 3 weeks, the implant-retained crown was ready for seating. The tall healing abutment was removed, exposing a healthy cuff of attached gingiva (Figure 11). The final screw-retained BruxZir zirconia crown (Glidewell) was torqued to 35 Ncm using a seating jig to stabilize the crown during torqueing of the abutment screw. The access hole was covered over with a composite restoration (Figure 12). The periodontal health of the implant was maintained. The screw-retained prosthesis eliminated the need for cement to retain the crown.

The patient was provided with a tooth to help in chewing function.

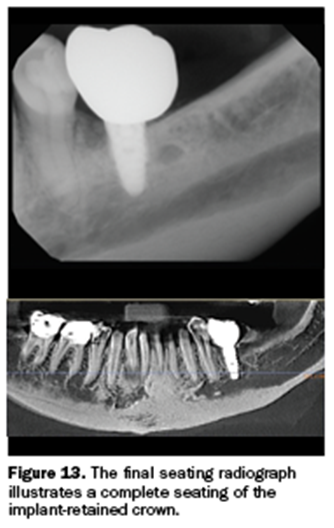

The final digital radiograph illustrates a complete seating of the crown significantly away from being disturbed and vital anatomy (Figure 13).

Differences exist between the tissue around natural teeth and dental implants. A junctional epithelium serves as the attachment of the implant to the oral mucosa. Natural teeth have a connective tissue attachment apically that is not apparent around dental implants.13,14

The oblique and parallel fibers around dental implants are not connected, and thus there is no periodontal ligament present. Since there is no vascular attachment, bacterial invasion is possible; thus, a firm band of attached gingiva on the facial aspect of the implant is critical to a healthy periodontal state.7,8 Without a keratinized band, there is a potential for inflammation with improper plaque control. This can affect the implant as the inflammation eventually extends apically around the implant body itself.

The literature indicates that a minimum band of at least 2.0 mm of keratinized tissue around an implant will help reduce inflammation and trauma caused by brushing.7 The best way to determine the availability of attached gingiva is to infiltrate the surgical site prior to surgical intervention.

The anesthetic fluid will lift the mucosal tissue, and the mucogingival line will become apparent.

CONCLUSION

Dental implants have been proven to be an outstanding alternative to conventional removable appliances in creating function and aesthetics for our patients.15,16 Having fixed prostheses eliminates the need to remove the appliances and improves the patient’s psychological quality of life. Taking a tooth-down approach to diagnosing and treatment planning any dental implant will help to communicate to the patient the final result and also help the dentist design an implant-retained prosthesis with an excellent long-term prognosis.

Vital anatomy needs to be clearly understood. With the advent of CBCT analysis and virtual placement of our dental implants and the evaluation of crown design using planning software, the practitioner can visualize the entire case finished before ever starting. The possibility of surgical placement can be seen preoperatively, and the dentist may determine if the case is within his or her wheelhouse or if other options should be considered. The positions of the mandibular and mental nerves, as well as the maxillary sinuses, are a concern.

Modern technology allows us to be able to view vital anatomy precisely. Although bone morphology is easily visualized, one common error made is not recognizing the lack of attached gingiva on the facial aspect of our surgical sites.

Once recognized, the problem is easily corrected with a simple periodontal technique.

References

1. Hwang D, Wang HL. Medical contraindications to implant therapy: part I: absolute contraindications. Implant Dent. 2006;15(4):353–60. doi:10.1097/01.id.0000247855.75691.03

2. Hwang D, Wang HL. Medical contraindications to implant therapy: part II: relative contraindications. Implant Dent. 2007;16(1):13-23. doi:10.1097/ID.0b013e31803276c8

3. de-Freitas NR, Lima LB, de-Moura MB, et al. Bisphosphonate treatment and dental implants: A systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2016;21(5):e644-51. doi:10.4317/medoral.20920

4. Flanagan D. Osseous remodeling around dental implants. J Oral Implantol. 2019;45(3):239–46. doi:10.1563/aaid-joi-D-18-00130

5. Mandelaris GA, Rosenfeld AL, King SD, et al. Computer-guided implant dentistry for precise implant placement: combining specialized stereolithographically generated drilling guides and surgical implant instrumentation. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2010;30(3):275–81.

6. Kern JS, Kern T, Wolfart S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of removable and fixed implant-supported prostheses in edentulous jaws: post-loading implant loss. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2016;27(2):174–95. doi:10.1111/clr.12531

7. Tetè S, Zizzari VL, Borelli B, et al. Proliferation and adhesion capability of human gingival fibroblasts onto zirconia, lithium disilicate and feldspathic veneering ceramic in vitro. Dent Mater J. 2014;33(1):7-15. doi:10.4012/dmj.2013-185

8. Ashurko IP, Tarasenko SV, Repina SI, et al. Keratinized attached gingiva around dental implants: the role, structure, increasing techniques. IAJPS. 2018;5(10):m10887-10891. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1472779

9. Lindhe J, Berglundh T. The interface between the mucosa and the implant. Periodontol 2000. 1998;17:47-54. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0757.1998.tb00122.x

10. Schrott AR, Jimenez M, Hwang JW, et al. Five-year evaluation of the influence of keratinized mucosa on peri-implant soft-tissue health and stability around implants supporting full-arch mandibular fixed prostheses. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20(10):1170–7. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01795.x

11. Berglundh T, Lindhe J, Ericsson I, et al. The soft tissue barrier at implants and teeth. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1991;2(2):81-90. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0501.1991.020206.x

12. Adibrad M, Shahabuei M, Sahabi M. Significance of the width of keratinized mucosa on the health status of the supporting tissue around implants supporting overdentures. J Oral Implantol. 2009;35(5):232–7. doi:10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-09-00035.1

13. Warrer K, Buser D, Lang NP, et al. Plaque-induced peri-implantitis in the presence or absence of keratinized mucosa. An experimental study in monkeys. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1995;6(3):131-8. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0501.1995.060301.x

14. Kim BS, Kim YK, Yun PY, et al. Evaluation of peri-implant tissue response according to the presence of keratinized mucosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(3):e24–8. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.12.010

15. Oh SH, Kim Y, Park JY, et al. Comparison of fixed implant-supported prostheses, removable implant-supported prostheses, and complete dentures: patient satisfaction and oral health-related quality of life. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2016;27(2):e31–7. doi:10.1111/clr.12514

16. Brennan M, Houston F, O’Sullivan M, et al. Patient satisfaction and oral health-related quality of life outcomes of implant overdentures and fixed complete dentures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2010;25(4):791-800.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Kosinski received his DDS degree from the University of Detroit Mercy School of Dentistry (Detroit Mercy Dental) and his Mastership in Biochemistry from the Wayne State University School of Medicine. He is an affiliated adjunct clinical professor at Detroit Mercy Dental; serves on the editorial review board of REALITY, the information source for aesthetic dentistry; and is the past editor of the Michigan Academy of General Dentistry Update.

He is currently the editor of the AGD journals General Dentistry and AGD Impact and is the editor of Implants Today in Dentistry Today. He is a past president of the Michigan AGD. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Oral Implantology/Implant Dentistry, the International Congress of Oral Implantologists, and the American Society of Osseointegration. He is a Fellow of the American Academy of Implant Dentistry and received his Mastership in the AGD.

He can be reached at drkosin@aol.com or via the website smilecreator.net.

Disclosure: Dr. Kosinski reports no disclosures.