A recent report by BBC News seriously questioned the loss of manual dexterity among British medical students trained for surgery.

“It is important and an increasingly urgent issue,” said Dr. Roger Kneebone, professor of surgery at Imperial College in London. “It is a concern of mine and my scientific colleagues that whereas in the past you could make the assumption that students would leave school able to do certain practical things—cutting things out, making things—that is no longer the case.”

Kneebone emphasized that surgeons require craftsmanship as well as academic knowledge. Young people need well-rounded skillsets such as arts and crafts so they learn to use their hands, he said.

“A lot of things are reduced to swiping on a two-dimensional flatscreen,” said Kneebone, contending that such swiping diminishes the experience of handling materials and developing physical skills.

Others would disagree. Some researchers say that the old chalk carving testing was meaningless since students could achieve necessary hand skills as students. In fact, others argue that students who played video games learned faster, generated fewer clinical errors, and preformed surgical tasks faster.

Possible Extrapolation to US Dental Students?

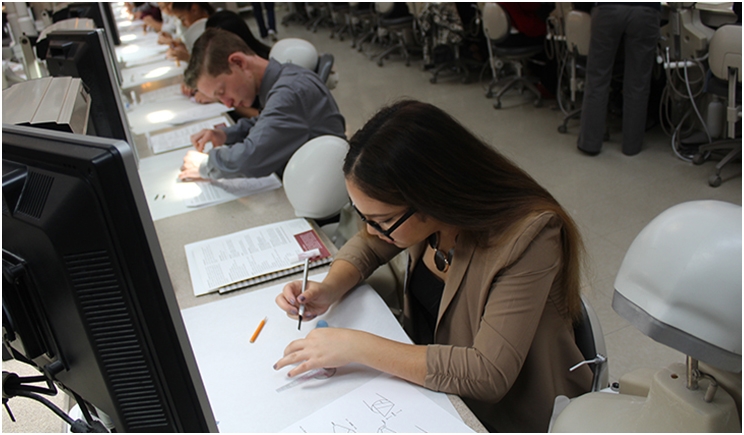

In the modern digital age, are dental students less able to handle the challenges demanded in manual dexterity? Does the time spent manipulating a flat two-dimensional screen come at the expense of developing the hand-eye skills essential for a clinical dentist?

“I think we see as many outstanding, gifted, and technically skilled students as ever,” said Anthony Silverstri Jr, DMD, a clinical professor at the Tufts University School of Dental Medicine.

“However, as class sizes have grown larger and larger over the years, the number of less outstanding, less gifted, and less technically skilled students may have grown as well. It may well just be a numbers thing,” continued Silvestri.

“The number of technically gifted students in any applicant pool is finite. The number of less gifted applicants is not. The range of technical skills of incoming students, between the most competent and the least competent, therefore, may be stretching out in a disproportionate way,” said Silvestri.

“Unless we have data to support a statement regarding class sizes and technical skills, I personally would refrain from stating this,” countered Andrea Ferreira Zandona, DDS, MSD, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Comprehensive Dentistry at the Tufts University School of Dental Medicine

“There is one other thing. The ‘business’ of dental education has changed over the years as well. Gone are the days of rigid, draconian, sometime unrealistic technical standards and hurdles we all had to conquer as young dental students decades ago,” Silverstri added.

“Technical skill expectations on the part of teachers are not what they used to be. Materials are easier to handle and less technique sensitive as well. And, there is an expectancy on the part of student, teacher, and administrator alike that once admitted to school, graduation is a near certainty,” concluded Silvestri.

“As materials have improved and become less technique sensitive and more understanding of the connection of oral health and overall health is gained, dentistry is moving towards more prevention and health management,” said Ferreira Zandona.

“Dentistry remains a surgical specialty, and it is critical that selection of candidates includes manual skills as well as intellect,” said Paul S. Casamassimo, DDS, MS, a member of the Section of Dentistry at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and a professor of pediatric dentistry at the Ohio State University College of Dentistry.

“The pace of advance of technology and the continued onslaught of infectious disease mean that the next generation of dentists will need to have hand skills and can’t rely on medical management of oral diseases,” advised Casamassimo.

Live Patient or Typodont Examination

Dexterity and hand skills are of paramount importance for clinical dentists. Training in these requisite skills is vital to the ultimate welfare of patients. Admission of applicants of lesser abilities and expanding numbers of dental school graduates should not be at the expense of essential clinical skills.

Training of past generations of doctors may have included a substantial degree of incivility. Verbal abuse by faculty toward students was common and often tantamount to a professional hazing ritual. Some felt this “boot camp” philosophy was essential for refining a doctor’s abilities.

Today, faculty must comport with ethical codes of conduct. Training should not be draconian, as Silvestri said. But has the pendulum swung too far in the other direction? Or are other factors in play?

Modern dental board exams without live patients have been proposed. Development and demonstration of skills are achieved on artificial typodonts, which don’t squirm, fidget, or jerk.

Reassuring words or a comforting touch are meaningless. Typodonts don’t feel pain, cough, or sneeze. Their jaw muscles never tire, they don’t require periodic breaks, and they always remain 100% stationary. Every typodont is identical and replicated within duplicate mechanical standards. Testing criteria, although highly artificial, are absolutely consistent.

In essence, many dental students are trained like aircraft pilots who have only experienced flight simulators. They rarely if ever enter a live cockpit, where real people’s health and wellbeing are on the line. Things can and do go wrong (iatrogenic) on live patients, who have a vastly more complex set of variables. Yet each individual student may share equally superior hand dexterity skill sets.

It’s one matter to prepare and restore an artificial tooth on an inanimate typodont. It’s a completely different issue to provide that same service on a 5-year-old child with the attention span of a gerbil. Theoretically, both activities require identical finely tuned sets of skills. However, one potentially involves a moving target.

Groups like the ADA, the American Dental Education Association, and the American Student Dental Association advocate for standardized typodont testing. They contend attestation by a student’s professors should be adequate for clinical competency on live patients.

These entities purport artificial uniform test criteria are more equitable to the examinees. The nearly infinite variables of real-world clinical dentistry can be eliminated from testing. Is that seemingly contrived exam criteria in the public’s best interest?

The American Association of Dental Boards (AADB) supports blind competency examination on live patients so examiners are never in contact with the examinee. A potential bond or conflict of interest may develop between students and their professors that might affect judgement of the students’ clinical abilities. An independent and impartial arbiter of the testing on real patients under true clinical conditions should be the judge for licensure, contends the AADB.

“If people knew how hard I worked to get my mastery, it wouldn’t seem so wonderful at all,” said Michelangelo.

Dr. Davis practices general dentistry in Santa Fe, NM. He assists as an expert witness in dental fraud and malpractice legal cases. He currently chairs the Santa Fe District Dental Society Peer-Review Committee and serves as a state dental association member to its house of delegates. He extensively writes and lectures on related matters. He may be reached at mwdavisdds@comcast.net or smilesofsantafe.com.

Related Articles

Is Need or Demand the Driving Force for a New Texas Dental School?

Today’s Dental Grads Face Big Debt and More Choices

Trends Evolve in Dental School Admissions