The goals of aesthetic dentistry and medicine are to assist patients in looking their best while maintaining a natural and healthy appearance. Patients presenting for Botox [Allergan] and/or dermal fillers commonly place disproportionate focus on the middle and upper areas of the face.

It’s often necessary to educate patients regarding the contribution of the lower third of the face to the aging process as a whole. Aging is a pan-facial event, and the astute clinician will aid the patient in evaluating all three (upper, middle, and lower) facial segments.

For example, a 63-year-old female presents with the chief complaint that she doesn’t like her “jowls” and feels that area makes her “look older” (Figures 1 and 2).

|

|

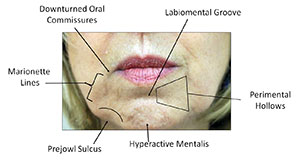

| 1. A 63-year-old female patient was unhappy with the “jowling” on her face. | 2. Specific terminology identifies the key features of the lower third of the face. |

The patient’s marionette lines, while not deep, present diffuse shadowing on her right side. The prejowl sulci exhibit heavy shadowing. Surface irregularities on the chin produce punctate shadows that further direct the viewer’s eye to the lower mandible.

Though not dramatic, the right oral commissure curls inferiorly and spills into the marionette line. The inferior labial shadow located just superior to the chin suggests development of a labiomental crease.

Despite modest volume loss, the patient’s lips appear to be proportionally balanced. Along with perioral rhytids, the vermillion-white roll junction has lost its crisp border. Neither feature is glaring, though, and the patient’s main concern is jowling. Gaining patient confidence by satisfactorily treating the focal area often leads to treatment of other areas. (Figure 3).

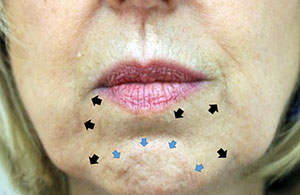

|

|

| 3. The black arrows indicate marionette lines. The yellow arrows indicate prejowl sulci. The blue arrows indicate a hyperactive mentalis muscle. And, the red arrow indicates labiomental groove formation. | 4. The patient requested treatment (before, left). The dentist injected 4 units of Botox in the mentalis muscle followed by 1 cc or Restylane Lyft in the perimental hollows and marionette lines, with 0.33 cc in each prejowl culcus. |

Treatment Sequence

Treatment begins by placing 4 units of Botox in the mentalis muscle to greatly reduce the irregular surface topography and create a calmer chin appearance. Pre-treating the area with neurotoxin also is expected to increase the residency time of the dermal filler1 and decrease the amount of filler required to correct the

Neurotoxins require approximately 10 days to reach maximum clinical effect. Phase 2 of treatment is scheduled to occur after the therapeutic effect has begun. Postoperative instructions are given and the patient is dismissed.

The patient returns for the second phase of treatment 2 weeks after neurotoxin treatment. The hyaluronic acid dermal fillers are selected based on their biochemical properties and the injection site.

After the patient’s skin is cleansed to remove any cosmetics or moisturizer, 2% chlorhexidine with 70% alcohol wipes are used as a skin prep. A total of 1 cc of Restylane Lyft [Galderma Laboratories LP] is placed using a blunt-end cannula in the perimental hollows and marionette lines.

Each prejowl sulcus receives 0.3 cc of Juvederm Voluma [Allergan] using a sterile 27 gauge 0.5-inch needle. Postoperative instructions are reviewed, and postoperative photographs are taken (Figure 4).

The patient is pleased with her outcome and understands she must return every 3 to 4 months for neurotoxin maintenance. Photodocumentation at these visits aids in determining the need for and timing of her next dermal filler treatment.

|

|

| 5. The 5 A’s for facial injectables include anatomy, aging, adjacent structures, aesthetics, and approach. | 6. The face can be divided into upper, middle, and lower thirds for aesthetic treatment. |

Evaluation Algorithm

The treatment planning of facial injectables should comprise the 5 A’s: anatomy, aging, adjacent structures, aesthetics, and approach (Figure 5).

Understanding the relevant anatomy of the area in question and whether the clinician has the knowledge, skill, and training to treat the presenting defect is the deciding factor as to whether the case moves beyond the consultation level. The case should be referred to another practitioner or specialist if these criteria are not met.

Next, knowing where to look for the contributions of facial aging is a key element in the ability to adequately address the patient’s chief complaint.

The contribution of adjacent structures to the focal defect and the ability to relay this information to the patient in a way that the patient can understand vastly increases the likelihood of treatment acceptance and success.

Symmetry plays a major role in the perception of beauty. Understanding phi (the golden ratio) and how it pertains to the facial elements is helpful when evaluating and planning treatment. The ability to satisfactorily alter the facial form requires a deep understanding of facial aesthetics.

Finally, the approach involves selecting the injectable modality. Neurotoxin, dermal filler, or a combination, along with educating the patient as to the treatment plan and its expected outcome, longevity, and maintenance, collectively influence case success and patient satisfaction. Factors such as placement depth (upper-, mid-, or deep-dermis or supra-periosteal) as well as desired textural outcome (firmness versus softness) dictate dermal filler product selection.

Lower Face Anatomy

A full command of the anatomy in any area of intended injection vastly decreases the probability of adverse events and greatly increases the injector’s confidence.

The skin of the chin is some of the thickest on the face.2 Dermal thinning, which occurs most rapidly in postmenopausal women,3 may cause the skin of the chin to adopt an orange peel appearance—hence the name “peau d’orange.” This results from hypertonicity of the mentalis muscle that connects to the dermis via dense fibrous septae.

The face contains discrete fat compartments that, with age, experience volume decreases and increases in a nonuniform manner.4

Unlike the muscles of mastication, which have bidirectional boney attachments, the muscles of facial expression are connected to the overlying skin via a layer called the superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS). When a facial muscle contracts, the overlying skin moves with it.

Vascular supply to the chin arises from two main branches of the facial artery: the inferior labial artery and the submental artery. Likewise, venous drainage is accomplished via the inferior labial vein and submental vein and ultimately to the jugular vein. Lymphatic drainage of the chin is principally to the ipsilateral submental lymph nodes.

Location of the mental foramen is somewhat variable. Anatomical studies show that in 50% of cases, the mental foramen is immediately buccal to the second bicuspid. In 25% it’s found between the first and second premolar, and in the remaining 25% it’s found posterior to the second premolar. The foramen’s vertical location, even in the senescent mandible, is greater than 8 mm superior to the inferior border of the mandible.5

Age-Related Changes

Aging results from intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include loss of collagen and volume loss from both fat and bone. Extrinsic factors include smoking, photodamage, and pollution.

Downturned oral commissures imply a loss of lip volume leading to an inferomedial curling of the commissure that dissolves into the marionette line. Presentation is magnified by a greater muscular pull from the depressors than the elevators of the corner of the mouth. A common complaint from patients presenting for facial rejuvenation is that their family members tell them they “look sad or annoyed.”

Genetics, loss of fat volume, skeletal remodeling, dermal thinning, and ptotic skin all contribute to marionette lines. Perimental hollows result from fat depletion, dermal thinning, and bony resorption.6

The prejowl sulcus forms a notch bilaterally on the mandibular border, located at the caudal terminus of the marionette lines. This sulcus is due to a combination of soft-tissue atrophy and bony resorption.7

A hyperactive mentalis muscle produces a pebbled and irregularly textured appearance of the chin integument. Sustained hypertonicity creates a permanent labiomental groove that is highly resistant to dermal filler treatment without concomitant treatment with neurotoxin.

Continuous observation and study of average, unattractive, and beautiful faces, both young and old, is the way to master clinical evaluation for diagnosis and treatment of patients seeking facial injectable treatment. The ability of the practitioner to detect details eluding the untrained eye is fundamental to providing clinical excellence.

Consultation

When developing a 3-D approach to lower face rejuvenation, tailoring treatment to the specific needs of the patient is crucial. Understanding where to look for age-related changes is indispensible to the diagnosis and integral to successful treatment outcomes.

Patients are rarely able to identify specific areas in their lower face that are responsible for the evidential signs of aging. They simply know that the area conveys a look of sadness, discontent, or fatigue that they would like changed.

A hand mirror aids in allowing the patient to point to the areas of concern. It also gives the practitioner the opportunity to inform and demonstrate to the patient the collective etiology in the problem area.

It’s important to assess a patient’s motivation for injectable treatments. Research indicates that patients with internal motivations, such as the desire to feel better about their appearance, are more likely to be happy with their results than those with external motivations, which include patients primarily interested in some perceived reward, such as a more successful career or to please a significant other.8

The practitioner is obliged to discuss what can be accomplished with facial injectables and establish realistic expectations by the patient. This requires educating the patient regarding areas that contribute to an aged appearance as well as the limitations of injectables, risks, possible adverse events (ie informed consent), and costs. Furthermore, the patient should be apprised of what might be best handled surgically and the proper referral made when injectables are not indicated.

A medical history review including relevant medications and any prior history of facial surgeries or prior treatment with facial injectables (including type, if known) is completed. The importance of quality pretreatment photographs cannot be overstated.

In Summary

Each facial third has its own focal point. In the upper face, it’s the eyes. In the middle third, it’s the nose. In the lower face, it’s the lips (Figure 6). When evaluating the lower third, most clinicians and patients place a high value on lip enhancement and neglect adjacent tissues.

These areas, which include the chin, oral commissures, prejowl sulcus, perimental hollows, marionette lines, and labiomental grooves, all contribute greatly to the aggregate aging presentation and remain untreated or undertreated by most practitioners.

The lower face and perioral region offers a relatively well-understood zone for the dentist new to the facial injectable world. Although not completely without risk, the anatomy of this area is familiar to the dentist and represents a lower risk of some of the more exigent adverse events.

The lips are absolutely vital to rejuvenation of the lower segment. However, treatment in isolation without addressing the perioral cutaneous tissues falls short of adequately addressing the senescent lower face.

References

- Küçüker I, Aksakal IA, Polat AV, et al. The effect of chemodenervation by botulinum neurotoxin on the degradation of hyaluronic acid fillers: an experimental study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:109-113.

- Ha RY, Nojima K, Adams WP Jr, et al. Analysis of facial skin thickness: defining the relative thickness index. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:1769-1773.

- Stevenson S, Thornton J. Effect of estrogens on skin aging and the potential role of SERMs. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2:283-297.

- Pessa JE, Rohrich Facial Topography: Clinical Anatomy of the Face. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012.

- Hollinshead WH. Anatomy for Surgeons: The Head and Neck. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1982.

- Zimbler MS, Kokoska MS, Thomas JR. Anatomy and pathophysiology of facial aging. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2001;9:179-187, vii.

- Shiffman MA, Mirrafati SJ, Lam SM, eds. Simplified Facial Rejuvenation. New York, NY: Springer; 2008:558.

- Proffit WR, White RP Jr, Sarver DM. Contemporary Treatment of Dentofacial Deformity. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2002.

Dr. Gigi Meinecke is the founder and principal of Facial Anatomy for Comprehensive Esthetic Seminars (FACES), the only facial injectable course to combine cadaver review workshops with live patient training. She has lectured nationally since 2010 on facial injectables and maintains a full-time private practice in Potomac, Md. She is the immediate past president of the Maryland Academy of General Dentistry and a Fellow in the International College of Dentists. She serves on the ADA Council on Communications and the AGD Legislative and Governmental Affairs Council, and she is a national spokesperson for the AGD.

Dr. Gigi Meinecke is the founder and principal of Facial Anatomy for Comprehensive Esthetic Seminars (FACES), the only facial injectable course to combine cadaver review workshops with live patient training. She has lectured nationally since 2010 on facial injectables and maintains a full-time private practice in Potomac, Md. She is the immediate past president of the Maryland Academy of General Dentistry and a Fellow in the International College of Dentists. She serves on the ADA Council on Communications and the AGD Legislative and Governmental Affairs Council, and she is a national spokesperson for the AGD.

Related Articles

Nevada Hygienists Approved to Perform Botox Procedures

Laser Dentistry Requires Bright Practice Management

Get Your Hygiene Patients “Off the Fence”!