The pursuit of fresh breath is important both socially and emotionally. The dental professional is expected to address this condition with patients, and yet this service has yet to be universally adopted and offered routinely. In light of recent research establishing the potential contribution of oral infection to certain systemic diseases,1 it has become even more critical for clinicians to find new ways to reduce the plaque mass and provide additional motivation for daily oral hygiene practices. This article reviews the research regarding oral malodor as well as the clinical and daily care protocols for the management of oral malodor.

BACKGROUND

The history of personal concerns with oral malodor is well documented.2 Dental professionals need to have a working knowledge of the causes, types, and management of oral malodor. Halitosis has been used to describe this condition, however, this term actually refers to an odor emanating from the gastric tract.2 Additional terminology regarding bad breath include the following: ozostomia, which is derived from the Greek term “ozo,” and refers to an odor from the respiratory tract; stomatodysodia, which is derived from the Greek term “stoma,” and refers to “mouth” or an opening in the abdominal tract; and fetor oris/fetor ex ore, which are Latin and French, respectively, and refer to an offensive odor that emanates from the mouth and has sources originating in the mouth. Systemic disorder-related malodor accounts for approximately 20% of bad breath conditions.3 The remaining 80% is attributed to oral and/or nasopharyngeal related conditions. As such, the appropriate term to describe malodor is oral malodor or non-oral malodor, the latter meaning a bad odor not eminating from the mouth.1 An estimated 40 million Americans suffer from oral related malodor,1 and patients frequently are interested in preventing, treating, or masking this condition.

|

Table 1. Proposed Clinical Protocol for Oral Malodor Management Management of OM A. Assessment Phase B. Clinical Protocol

Table 2. Active Agents for Neutralizing VSC and/or Reducing Infection •Zinc—the most recognized and effective VSC neutralizing agent Table 3. Oral Hygiene Recommendations for Fresh Breath •Automated toothbrushes |

Oral malodor (OM) is classified as either transitory or chronic. Transitory malodor is directly related to foods, medications, alcohol, or tobacco, and usually lasts no more then 72 hours. This type of malodor is easily masked via mouthwashes, chewing gum, or breath mints. The majority of malodor is chronic in nature, with seven possible sources: (1) mouth and tongue; (2) nasal, nasopharyngeal, sinus, and oropharyngeal structures; (3) xerostomia induced; (4) lower respiratory tract and lung; (5) systemic disease; (6) gastrointestinal diseases and disorders; and (7)odor-producing foods, fluids, and medications. Odor from the lower respiratory tract and lung is related to compromised pulmonary function and generally seen with these types of conditions. The best example of systemic related malodor is seen in the uncontrolled diabetic whose breath has a characteristic fruity odor. While gastrointestinal diseases produce odor from the GI tract, ingestion of odor-producing foods, liquids or medications will produce a transient odor that dissipates in 24 to 72 hours. As the majority of malodor is related to the mouth and tongue, nasal, nasopharyngeal, sinus, and oropharyngeal areas, and xerostomia, and with an estimated 80% to 90% originating in the oral cavity, intervention by the dental team is often required.1,2,4

THE ORAL CAVITY AS THE SOURCE OF ORAL MALODOR

The primary cause of oral-related malodor is the metabolism of epithelial cells by Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria, resulting in a production of volatile sulfur compounds (VSC). The VSC include hydrogen sulfide (H2S), methyl mercaptan (CH3SH), dimethyl sulfide, and dimethyl disulfide. While H2S can be detected from patients who are periodontally healthy, CH3HS is associated with those patients who have periodontal disease.5,6 The bacteria that produce VSC reside in the posterior dorsum of the tongue, gingival sulcus/ periodontal pockets, and the tonsillar tissue.

VSC have been associated with adverse effects on the host tissue. These compounds can cause an increase in mucosa permeability, which may permit bacteria and endotoxin to invade and may negatively impact on wound healing.5,7-9 These compounds have also been shown to interfere with collagen and protein synthesis, and suppress DNA synthesis.5,7-9 Research has also suggested that the presence of these compounds may accelerate the infection process via increased mucosal permeability and effect on local immune response.6 As a result, neutralizing VSC to eliminate odor may have even more importance than just the obvious cosmetic benefits.10

Consideration should focus on the niches that harbor Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. Periodontal pocketing of 4 mm or greater, the tonsillar region, and the posterior dorsum of the tongue are regions in which these bacteria accumulate. The correlation of pocket probing depths with OM production can provide patient motivation. The tonsillar tissue can also harbor bacteria, especially in the tonsillar crypts. Finally, the posterior dorsum of the tongue has been identified as a major causative area for OM. This area provides the ideal surface for retention of bacteria and food debris, and without daily cleansing will be a major source of VSC production. A typical tongue coating contains dead epithelial cells, food debris, white blood cells, and bacteria. Focusing on the cleansing of this area will assist in effective OM management.

Effective OM managment is accomplished through mechanical cleansing and chemotherapeutics to neutralize the VSC. This protocol fits well with general maintenance of oral health, but provides significantly more motivation over the traditional disease motivation model.6

DIAGNOSIS OF ORAL MALODOR

Quantitative diagnosis is a particularly challenging aspect of OM management (Table 1). This is because OM involves many variables, including the time of the day, length of time since the last meal, the patient’s age, etc. In terms of OM research, the gold standard for diagnostics is organoleptic judging. Individuals who can discern differences in odor in reference to a scale accomplish this. This is generally impractical on a clinical basis.

Clinical diagnostic tools are limited, but some are available. The Halimeter (InterScan) will measure VSC in the oral and nasal cavity.4 The device is more sensitive to hydrogen sulfide than to methyl mercaptan, and patients must refrain from consuming odor-producing foods, oral hygiene, and wearing any fragrance for at least 2 hours prior to the appointment. Hence, first appointments of the day are preferred. The BANA test detects the presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Bacteroides forsythus as these organisms produce a trypsin-like enzyme that hydrolyzes synthetic peptide (BANA). The results correlate with oral malodor.11,12 The Perio2000 periodontal probe detects the presence of sulfides. These devices can be very useful in determining clinical success for OM management, and can also be used as a measure of success of periodontal therapy.

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT OF ORAL MALODOR

Clinical management of OM begins during the examination and assessment phase of dental care. Clinicians should question patients on their daily use of products such as chewing gum, breath mints, or other oral care products. This will not only provide the clinician with information regarding the patient’s level of concern about bad breath, but could also uncover information regarding excessive consumption of sugar.

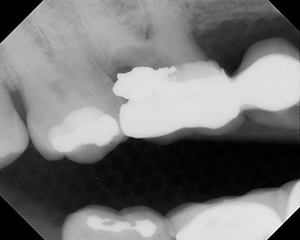

The careful examination of oral tissues is an essential part of patient assessment, and must include a thorough periodontal examination. Correlating probing depths with OM can provide a powerful motivation tool, so patients will be focussed on oral hygiene and follow-up assessments. Oral lesions and faulty restorations are noted, as are perioral findings such as the presence, size, and crypts of the tonsils. The coating of the tongue should also be recorded, including the color, amount, and area that is coated (Figure 1).

|

|

| Figure 1. Close-up of tongue plaque and debris. | Figure 2. Clinician deplaquing the tongue. |

|

| Figure 3. Close-up of tongue scraper. |

The clinical phase should continue to focus on removal of plaque via traditional oral hygiene procedures. Consideration for use of VSC neutralizing agents may assist in OM management. Pre- and post-procedural rinsing with neutralizing agents will decrease OM,13 and irrigating with these agents will neutralize subgingival VSC.14 The most effective means to control OM on a daily basis—tongue cleaning or deplaquing—should be reviewed at every preventive appointment. Many clinicians choose to deplaque the tongue at the conclusion of the appointment while having the patient watch the procedure (Figures 2 and 3). This alone will significantly reduce OM, and will provide another excellent opportunity to discuss maintenance of fresh breath. Professional plaque and calculus removal are also essential.

For patients with periodontal disease, clinicians might consider implementing full-mouth disinfection (FMD). This is a procedure that calls for full-mouth instrumentation within 24 hours and the adjunctive use of chlorhexidine. FMD research has shown this to be more effective than traditional quadrant scaling and root planing, with a greater gain in clinical attachment, greater reduction in probing depths, eradication of P gingivalis, greater reduction in spirochetes and motile organisms subgingivally, and greater reduction in oral malodor, with the results being maintained 8 months post instrumentation.15,16 Suggested modifications to the protocol include use of powered instrumentation, tongue scraping versus tongue brushing, and use of locally delivered antimicrobial agents at the 2-month evaluation phase.17

DAILY FRESH BREATH MAINTENANCE

As the preventive appointment concludes, the clinician should reinforce the fresh breath maintenance protocol. An additional approach to breath maintenance involves an increase in salivary flow. Methods to increase salivary flow include consumption of foods and the use of chewing gum or mints. Patients should be told to select only those gums and mints that are sugar free. Of even greater potential to the patient is the selection of a gum or mint that contains an active ingredient. For example, many sugarless gums and mints are sweetened with xylitol, which is known to be effective against Streptococcus mutans.18,19 Use of these products can significantly assist in maintaining fresh breath throughout the day when access to oral hygiene is limited.

The cornerstone of fresh breath maintenance is the daily removal of bacteria that produce VSC, as well as removal of food particles that become trapped throughout the oral cavity, including the posterior dorsum of the tongue. The main addition to the traditional oral hygiene regime should be daily tongue cleaning. Data have shown that cleaning the surface of the tongue is important.20,21 Devices specifically designed for deplaquing the tongue are effective and safe for patient use.20,22 When combined with use of VSC neutralizing agents such as zinc-containing compounds4,13 this process will result in longer lasting fresh breath (Tables 2 and 3).

Tongue cleaning should take place at least daily, and even more frequently for those patients with a heavier tongue coating. Morning deplaquing may be easier for patients prone to gagging, and some even complete the procedure in the shower. This simple procedure will dramatically improve bad breath.22,23 Additional consideration of appropriate tools should include automated oral hygiene devices and interproximal cleansing aids. Automated plaque control devices provide a safe and effective means for plaque removal that does not require much skill on the part of the user. Given that the average amount of time spent by patients on oral hygiene routines is 24 to 60 seconds,24 any method that can be employed to be more effective within this span of time should be considered advantageous.

CONCLUSION

Pursuit of fresh breath will continue to be of interest to virtually all dental patients. The dental clinician is the ideal professional to address fresh breath concerns with patients. Additionally, patients have come to expect this type of assessment and intervention.25 Clinicians would be well served to incorporate oral malodor management and education programs into their office protocol. As patients become aware of approaches to managing OM, a program in the dental office that educates patients will help to both address the problem and improve the general level of oral hygiene achieved by those under care.

References

1. American Academy of Periodontology. Position paper: peridontal disease as a potential risk factor for systemic diseases. J Periodontol. 1998:69:841–849.

2. Clark GT, Nachnani S, Messadi DV. Detecting and treating oral and nonoral malodors. CDA J. 1997;24:133-143.

3. Tonzetich J. Production and origin or oral malodor: a review of mechanisms and methods of analysis. J Periodontol. 1997;48:13–20.

4. Rosenberg M, et al. Bad Breath Research Perspectives. Tel Aviv, Israel: Ramot Publishing, Tel Aviv University; 1995.

5. Yaegaki K, Sanada K. Biochemical and clinical factors influencing oral malodor in periodontal patients. J Periodontol. 1992;63:783–789.

6. Ratcliff PA, Johnson P. The relationship between oral malodor, gingivitis, and periodontitis. a review. J Periodontol. 1999;5: pages?

7. Ng W, Tonzetich J. Effect of hydrogen sulfide and methyl mercaptan on the permeability of oral mucosa. J Dent Res. 1984;63:37–46.

8. Klokkevold P. Oral malodor: A periodontal perspective. CDA J. 1997; 24:153-159.

9. Bosy A, Kulkarni GV, Rosenberg M, McCullough CAG. Relationship or oral malodor to periodontitis: evidence of independence in discrete subpopulations. J Periodontol. 1994;65:37–46.

10. Johnson PW, Yaegaki K Tonzetich J. Effect of methymercaptan on synthesis and degradation of collagen. J Periodont Res. 1996;31:323–329.

11. DeBoever EH, DeUzeda M, Loesche WJ. Relationship between volatile sulfur compounds, BANA-hydrolyzing bacteria and gingival health in patients with and without complaints of oral malodor. J Clin Dent. 1994;4:114–119.

12. Kozlovsky A, Gordon D, Gelernter WJ, et al. Correlation between BANA Test and Oral Malodor Parameters. J Dent Res. 1994;73:1036–1042.

13. Nacnani S: The effects of oral rinses on halitosis. CDA J. 1997;24:145–150.

14. Quirynen M, Mongardini C, van Steenberghe D. The effect of a 1-stage full-mouth disinfection on oral malodor and microbial colonization of the tonuge in periodontitis patients, a pilot study. J Periodontol. 1998;69:374–381.

15. Quirynen M, Bollen CML, Vandekerckhove BNA, et al. Full-mouth versus partial-mouth disinfection in the treatment of periodontal infections. J Dent Res. 1995;74:1459–1467.

16. Mongardidi C, van Steenberghe D, Dekeyser C, et al. One stage full- versus partial-mouth disinfection in the treatment of chronic adult or early-onset periodontitis. I: long term clinical observations. J Periodontol. 1999;70:632–645.

17. Bernie KM. Full-mouth disinfection: an overview of research and clinical application. Hyg Report. 2001;5:10–13.

18. Simons D. Brailsford S, Kidd EAM, et al. The effect of chlorhexidine acetate/xylitol chewing gum on the plaque and gingival indices of elderly occupants in residential home. J Clin Perio. 2001;28:1010-1015.

19. Hildebrandt GH, Sparks BS. Maintaining mutans streptococci suppression with xylitol chewing gum. JADA. 2000;131:909–916.

20. Christensen G: Why clean your tongue? JADA. 1998;129:1605-1607.

21. van Steenberghe D, Rosenberg M. Bad Breath: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press; 1994.

22. Tonzetich J, Ng SK. Reduction of malodor by oral cleansing procedures. Oral Surgery Oral Med Oral Pathology. 1976;42:172–181.

23. Christen AG, Swanson B. Oral hygiene: a history of tongue scraping and brushing. JADA. 1978;96:215–219.

24. Cancro LP, Fischman SL. The expected effect on oral health of dental plaque control through mechanical removal. Periodont 2000. 1995;8:60–74.

25. White E. Bad breath in your future? Dent Product Report. 2000:86–94.

Ms. Bernie holds RDH and BS degrees in dental hygiene and is cofounder and director of Educational Designs, a national marketing and consulting company. She lectures nationally on infection control, innovations in periodontal therapy, and aesthetic dental hygiene, including oral malodor, and is an active member of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association. She also serves as a section editor for the Journal of Practical Hygiene. She can be reached at (925) 735-3238 or kmenageb@aol.com.