|

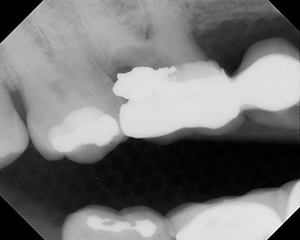

| Figure 1. Sagittal view of the maxillary sinus showing the proximity of the roots of the maxillary teeth |

|

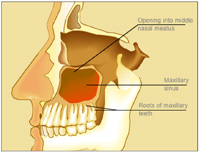

| Figure 2. Periapical radiograph of maxillary teeth and sinus floor |

There are 7 sinuses (air-filled cavities) in the head. They include the maxillary, ethmoid, mastoid, sphenoid, and frontal sinuses (the frontal sinuse is the only sinuse that is not bilateral).1 Sinusitis, an inflammation of the sinuses, is a common problem affecting almost all people at some point in their lives. It is a chronic problem for approximately 15% of the population (>31 million people) in the United States.2,3 A study done by the Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research revealed that in 1992 Americans spent 2 million dollars in prescription cold medications and more than 2 billion dollars for over-the-counter medications.4 Another study showed that acute and chronic sinusitis was the fifth most common diagnosis for which antibiotics were prescribed. That study noted that there was also a trend toward using more expensive, broad-spectrum antibiotics.5 Causes of the inflammation that lead to sinusitis can include allergic responses, chemical irritation, infections, mechanical obstruction, and an infected maxillary tooth.6,7,8 Approximately 10% of sinusitis is due to a dental source.2

THE DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

| Table 1. Steps to evaluate sinus pain versus tooth pain |

|

When attempting to make a diagnosis of pain in the maxillary posterior region, the dentist must first rule out a problem of dental origin. The differentiation of odontogenic pain from sinus pain includes consideration of the history of the pain and whether the patient has a history of sinusitis10 (Table 1). The radiographic evaluation includes a periapical x-ray and possibly a panographic x-ray. A radiograph commonly used by physicians and oral maxillofacial surgeons to diagnose sinusitis is a Water’s view, an anterior-posterior radiograph. If available, a computerized tomography scan can be helpful. The last 2 imaging techniques focus primarily on the sinus and are not usually useful to rule out teeth as the source of the problem/pain. An increased fluid level in the sinus may indicate an infection.12 This will help determine the status of the tooth and the proximity of the roots of the maxillary posterior teeth to the sinus (Figure 2). The clinical evaluation consists of palpation over the sinus and an examination of the teeth, including assessment of tooth vitality.

| Table 2. Common signs and symptoms of sinusitis |

|

It is certainly possible that an infected tooth can cause a sinusitis. Usually the first maxillary molar is involved because of its location.6 If this is the case, the radiograph may reveal an obvious periapical radiolucency, a widened periodontal ligament space at the apex of a tooth, or a tooth with extensive restorations and/or caries. A tooth that is in the area of complaint may also be sensitive to percussion or test negative when vitality is evaluated. It should be noted that there are a variety of sources of pain in the maxillary posterior region. Depending on the presentation and the results of the clinical and radiographic evaluation, all should be considered. These are listed in Table 3. It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss these other sources of pain.

TREATMENT

| Table 3. Possible sources of pain in the maxillary area |

|

If the dentist suspects acute sinusitis (duration of less than 4 weeks6) as the source of a patient’s dental pain, the dentist can either refer the patient to a physician to manage the sinusitis or can treat the sinusitis with the intention of ruling out that problem as the source of the dental pain. If there are clear indications of sinusitis, the option of referring the patient to a physician may be preferred.

| Table 4. Decongestants (sympathomimetics) used to treat sinusitis |

|

Topical decongestants:

Systemic decongestants:

|

| Table 5. Antihistamines used to treat sinusitis |

|

Sedating:

Nonsedating:

|

| Table 6. Antibiotics used to treat acute sinusitis |

Antibiotic of choice for penicillin-allergic patients:

Antibiotic of choice for penicillin and sulfa allergic patients:

|

| Table 7. Prescriptions for use in treating sinusitis to rule out a dental infection |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Most sinus infections are due to viral infections and can be treated with either topical or systemic sympathomimetic decongestants (Table 4). These are used to reduce tissue edema and allow drainage.6 Caution is needed, since the use of topical decongestants for more than 3 days can lead to rebound congestion that can confuse the clinical presentation and prolong the symptoms.2,6 It is also possible to use antihistamines to prevent or reduce edema (Table 5), but these drugs may promote drying of the mucosa and are less effective than a decongestant. Antihistamines are of benefit if there is an allergic component.2

SUMMARY

Sinusitis is a common medical problem that can occasionally manifest as dental pain. If the patient is experiencing dental pain in the maxillary posterior teeth, then it is appropriate for the dentist to rule out sinusitis as a source of the problem before proceeding with definitive dental treatment. Often there is an obvious odontogenic source of the pain, and this should be resolved first, but in other situations it is difficult to determine the cause of the symptoms. In some patients, the source of the pain is so equivocal that it may be necessary to treat the patient for sinusitis to eliminate this as the source of the dental pain (Table 7). In this process, the dentist has one of 2 options: either refer the patient to a physician or treat the sinusitis. The option chosen regarding patient management is made by the dentist and depends on the particular clinical situation and the dentist’s training and experience.

References

- Abubaker AO. Applied anatomy of the maxillary sinus. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North Am. 1999;11(1):1-14.

- Rogerson K. Microbiology of the maxillary antrum: treatment of infections. In: Kelly JJ, ed. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Knowledge Update. Vol 1. Rosemont, Ill: American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons; 1994:49-59.

- Piccirillo JF, Mager DE, Frisse ME, et al. Impact of first-line vs second-line antibiotics for the treatment of acute uncomplicated sinusitis. JAMA. 2001;286:1849-1856.

- Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Number 9: Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis. Rockville, Md: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1999. AHCPR publication 99-E015.

- McCaig LF, Hughes JM. Trends in antimicrobial drug prescribing among office-based physicians in the United States. JAMA. 1995;273:214-219.

- Julian R. Maxillary sinusitis, medical and surgical treatment rationale. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North Am. 1999;11(1):69-81.

- Abubaker AO, Benson KJ, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Secrets. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Hanley & Belfus, Inc; 2001:227.

- Bertrand B, Rombaux P, Eloy P, et al. Sinusitis of dental origin. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 1997:51:339-352.

- Wilk R. Physiology of the maxillary sinus. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North Am. 1999;11(1):15-20.

- Okeson JP, Falace DA. Nonodontogenic toothache. Dent Clin North Am. 1997;41:367-383.

- Sandler HJ. Clinical update—the teeth and the maxillary sinus: the mutual impact of clinical procedures, disease conditions and their treatment implications. Part 2. Odontogenic sinus disease and elective clinical procedures involving the maxillary antrum: diagnosis and management. Aust Endod J. 1999;25:32-36.

- Laine F. Diagnostic imaging of the maxillary sinus.Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North Am. 1999;11(1):45-67.

- Rafetto L. Clinical examination of the maxillary sinus.Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North Am. 1999;11(1):35-44.

- Haug R. The changing microbiology of maxillofacial infections. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North Am. 2003;15(1):2-15.

- Weymouth L. Microbiology of the maxillary sinus. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North Am. 1999;11(1):21-34.

- Flynn T. Principles of antibiotic selection. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North Am. 2003;15:17-38.

Dr. Jacobsen has a PhD in comparative pharmacology and toxicology. He is director of the Oral Medicine Clinic at the University of the Pacific Dental School. He is a diplomate of the American Board of Oral Medicine and past chairperson of the council on Dental Therapeutics of the ADA. He received the 1999 Gordon J. Christensen Lecturer Recognition Award and writes the Dental Drug Booklet, a succinct handout and reference on commonly prescribed dental medications.He can be reached at (415) 929-6609 or at pjacobse@sf.uop.edu.

Dr. Casagrande is an associate professor in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the University of the Pacific Dental School and is the director of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Training Program at Highland Hospital in Oakland Calif. She is trained in both medicine and dentistry.