As dental professionals, we tend to focus on what our patients need. However, if we don’t inquire about what is important to patients beyond standard oral health, we may lose an opportunity to serve them best. Adding cosmetic-related discussions with patients can be as simple as: “What do you like about your smile?” or “is there anything you would change about your smile?” Adding this extra layer in conversations with patients creates an opportunity to treatment plan what our patients might want versus only what they need. The broad selection of whitening products and claims in the marketplace is exciting but choosing ‘the right’ whitening product can feel overwhelming for professionals and consumers alike.

Levels of efficacy and patient tolerability among different products can oftentimes be confusing but enable a conversation and professional recommendation to your patients across a spectrum of in-office whitening procedures to at-home options. Understanding tooth color etiology, the relative strengths and limitations of treatment options, costs, and your patient’s goals is important for effective professional guidance.

Now, let’s get into the science!

Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) is the most researched whitening ingredient. While the H2O2 molecule is the same, differences in concentration and carrier impact its efficacy. It is recognized as a safe ingredient as the body naturally creates it as part of our protection against pathogens and can break it down1,2. Also, whitening does not affect the strength of hard tissues, the integrity of restorations, or restorative bonding3-5.

Carbamide peroxide (CH6N2O3) breaks down to Hydrogen Peroxide and urea in a 3:1 ratio, so 10% carbamide peroxide is equivalent to about 3% H2O2.

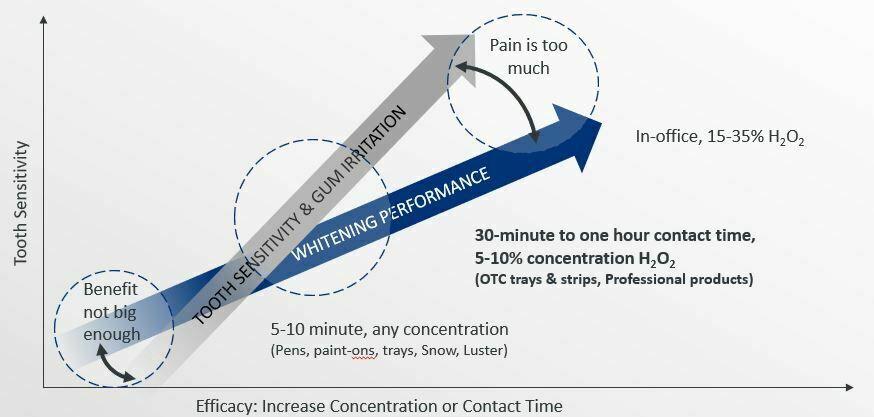

The efficacy and tolerability of bleaching products is contingent upon the agent’s concentration, dose, and contact time. At higher concentrations or dose, results may be faster; however, tolerability may be reduced (either sensitivity or gingival irritation). At low concentrations, the benefit may not be big enough to be worth the treatment time.

Retention is imperative for effectiveness and varies by delivery system. Don’t be confused by shade claims (e.g.: “5 shades whiter in three days”). It is well established that individual baseline color of the patients’ tooth impacts the speed of benefit. In other words, a young patient with yellow coloring will whiten faster than an older patient with gray or brown hues.

Most whitening compositions consist of hydrogen peroxide, water, a carrier such as glycerin, a thickening agent, and a pH adjusting agent to keep pH in the safe 5-7 range. These structured gels are based on hydrogen bonding to establish structure and give the gel adhesiveness and viscosity. The gels work well, however, the availability of the peroxide is limited because peroxide is part of the gel structure.

Also, the gels are not completely hydrated so they pull water out of the teeth during the whitening process, resulting in a temporary, non-harmful dehydration of the teeth, which can cause bleaching-related hypersensitivity and a transient whiter appearance that will regress once rehydrated8.

Crest Whitestrips are the #1 dentist recommended at-home whitening treatment and have delivered reliable at-home whitening for longer than two decades. The no-slip grip strips deliver an effective and safe whitening treatment without messy gels or trays. This is Crest’s fastest and most effective whitening solution.

Until now, the chemistry of the whitening procedures has been similar and has remained unchanged, except the concentration of peroxide and additive ingredients to treat the side effects of dentinal sensitivity.

Crest Whitening Emulsions is a game-changer of whitening chemistry. This new on-the-go, leave-on technology has recently been introduced, which uses a novel emulsion-based vehicle to facilitate peroxide delivery while minimizing dehydration, so patients experience virtually no sensitivity (no different than placebo).

Unlike traditional gels, which are a single-phase uniform mixture, emulsions consist of two phases — peroxide phase, which is hydrophilic (water-loving), and a carrier phase which is hydrophobic (water-hating) as petrolatum. In this emulsion, the phases remain separate because they don’t “like” each other, like oil & water.

The hydrophobic phase suspends the concentrated microdroplets (~25 microns) of the hydrogen peroxide until they come in contact with the tooth surface. The tooth surface is hydrophilic, as are the peroxide microdroplets, therefore when this whitening emulsion is applied to the tooth surface the peroxide is drawn out of suspension, offering peroxide that is uninhibited by the chemistry of thickening or gelling agents. When the peroxide is drawn out of the emulsion to the tooth surface, it creates a layer to begin the diffusion process through the enamel. As a result, the peroxide is delivered more efficiently and diffuses quickly to the stains to render them colorless and whiten the teeth.

Because the carrier phase is hydrophobic, it acts to protect the peroxide microdroplets from diluting away or being decomposed by salivary enzymes optimizing contact time. It renders the microdroplets of peroxide significantly more available and there is no inhibition of peroxide droplets to diffuse, unlike traditional delivery systems. Essentially the hydrophobic phase serves as the physical barrier during the whitening process so that no separate delivery device, like a strip or tray is needed. Even though you may not feel it, the composition remains on the teeth for 30 minutes or longer.

Tooth sensitivity experienced by some patients has remained a barrier to full utilization of vital tooth bleaching. The origins of dentinal hypersensitivity and bleaching related sensitivity are not the same. Whitening treatments produce minor, transient inflammation of pulp, which in turn elevates the response of pulp nerves. The inflammation could be caused by the over diffusion of peroxide into the pulp, or it may be exacerbated by dehydration effects which occur from anhydrous thickening agents in the gel that delivers the bleach6.

There is no contraindication for treating dentinal hypersensitivity via a product whose mechanism of action is tubule occlusion, as it does not impact efficacy of the peroxide. The peroxide is still able to diffuse to the chromogen. In fact, using a product that occludes tubules or contains potassium salts may reduce the sensitivity associated with hydrodynamic pull on pulpal fluids while the pulp is inflamed.7

How whitening works: When peroxide encounters a stain such as porphyrin, it takes electrons from the molecules in a process called oxidation. When an electron is removed from a molecule, most often it changes its ability to filter light, rendering it colorless. For this process to occur, the peroxide must be right next to the stain.

What do we know about LED light? It is fair to say that the performance of light activated bleaching has been controversial. Some light activated in-office bleaching systems have been re-examined for patient tolerability and efficacy in improving bleaching performance.9 In photo-oxidation (light enhanced) molecules absorb light energy, once a stain molecule absorbs enough energy its electrons reconfigure and it becomes easier for the peroxide to remove electrons from the molecule, rendering it colorless. Therefore, for light to be effective, the intensity and wavelength must be optimized, and peroxide must be in close proximity to the stain molecule.

For this reason, it is best to protect diffusion time to the site of chromogen stain first before applying the light (i.e., apply light at the end of the treatment, after diffusion). Use the Crest LED light at the end of the treatment to break down stains even better vs. Crest Whitening Emulsions alone.

REFERENCES

- Glorieux C, Calderon PB. Catalase, a remarkable enzyme: targeting the oldest antioxidant enzyme to find a new cancer treatment approach. Biol Chem. 2017 Sep 26;398(10):1095-1108. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2017-0131. PMID: 28384098.

- Khan, Amjad A et al. “Biochemical and pathological studies on peroxidases -an updated review.” Global journal of health science 6,5 87-98. 13 May. 2014, doi:10.5539/gjhs.v6n5p87

- White DJ, Kozak KM, Zoladz JR, Duschner HJ, Götz H. Effects of tooth-whitening gels on enamel and dentin ultrastructure–a confocal laser scanning microscopy pilot study. Compend Contin Educ Dent Suppl. 2000;(29):S29-34; quiz S43. PMID: 11908407.

- White DJ, Duschner H, Pioch T. Effect of bleaching treatments on microleakage of Class I restorations. J Clin Dent. 2008;19(1):33-6. PMID: 18500158

- Effect of Bleaching on Bond Strength of Composite Resin Bonded to Dentin D.J. WHITE1 , C. DOERFER2 , H. DUSCHNER3 , K.M. KOZAK1 , and T. PIOCH2 , 1 The Procter & Gamble Company, Mason, OH, USA, 2 University of Heidelberg, Germany, 3 Johannes Gutenberg-University, Mainz, Germany Research presented at the 81ST General Session of the IADR, June 25-28, 2003

- Vaz MM, et al. Inflammatory response of human dental pulp to at-home and in-office tooth bleaching. J Appl Oral Sci. 2016 Sep-Oct;24(5):509-517

- Markowitz K, Pretty painful: Why does tooth bleaching hurt?, Medical Hypotheses, Volume 74, Issue 5, 2010, Pages 835-840, ISSN 0306-9877, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2009.11.044

- Moghadam FV, et al. The degree of color change, rebound effect and sensitivity of bleached teeth associated with at-home and power bleaching techniques: A randomized clinical trial. Eur J Dent. 2013 Oct;7(4):405-411.

- SoutoMaior JR, de Moraes S, Lemos C, Vasconcelos BDE, Montes M, Pellizzer EP. Effectiveness of Light Sources on In-Office Dental Bleaching: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Oper Dent. 2019 May/Jun;44(3):E105-E117. doi: 10.2341/17-280-L. Epub 2018 Jun 12. PMID: 29893625.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Beth Jordan, RDH, MS is a graduate of Westbrook College, University of New England, Dental Hygiene, where she worked as adjunct clinical faculty for nearly 10 years and now serves on the college’s advisory committee.

She worked in private clinical practice until 2001 when she joined the Procter & Gamble Company (Crest Oral-B). Jordan is a member of ADHA and has served as a state delegate.

In 2011, she was recognized in Maine as “RDH of the Year” honored as a “catalyst for professional development.” She has contributed 2 chapters to the Darby Walsh dental hygiene textbook and has lectured to audiences of practicing dental professionals, students, and faculty. She has held several positions for the company and currently is a member of the Global Professional & Scientific Relations team where she contributes to scientific dissemination and passionately serves P&Gs commitment to oral health and prevention.