INTRODUCTION

Patients usually present to their dentists with TMJ problems. The usual treatment of nightguards may not best serve some patients. They may be suffering from many other quality-of-life-affecting health symptoms but didn’t see the need to mention those to their dentists. Careful review of medical history and medications prescribed for various symptoms would give the dentist a more complete clinical picture. Even routine dental treatment could severely exacerbate their symptoms. “First, do no harm.” Often, a dentist with the appropriate training might be the practitioner who could best diagnose and correct the root causes of many of these varied symptoms and conditions. This case report illustrates how an appropriate referral is in the best interests of such patients and the dentist.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

In March 2017, a 27-year-old female patient sought help for left TMJ pain that had been persistent and severe for 2 months and worsened with opening or chewing. She had dealt with this problem for 9 years with periodic flareups, but they were not prolonged or painful until 2 months ago. She was a Doctor of Pharmacy in her postdoctorate residency in Kansas City, Kan. Her family dentist in Louisiana had referred her to me for help with her TMJ problems.

The left TMJ pain level was reported as 7/10, even at rest, but escalated to 9/10 after a meal. Even eating soft bread was painful. She reported living on yogurt and smoothies for 2 months. She had a history of TMJ locking and limited opening 9 years prior, which was treated with a pull-forward splint for a year to increase opening and reduce pain. Joint clicking had remained since that time, with episodes of pain and limited opening. Dental history included orthodontia with first premolar extractions from age 10 to 14 to correct crowding.

On further questioning, she also reported a 3-year history of constant neck pain at 4/10 and a 5-year history of episodic mid-thoracic pain at 6 to 8/10. The other symptoms were 2 to 3 migraines per month, dizziness, ear pain, ear congestion, pain behind the eyes, fatigue, and non-restorative sleep.

Her health history also revealed prescriptions for Lexapro for depression and Vyvanse for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

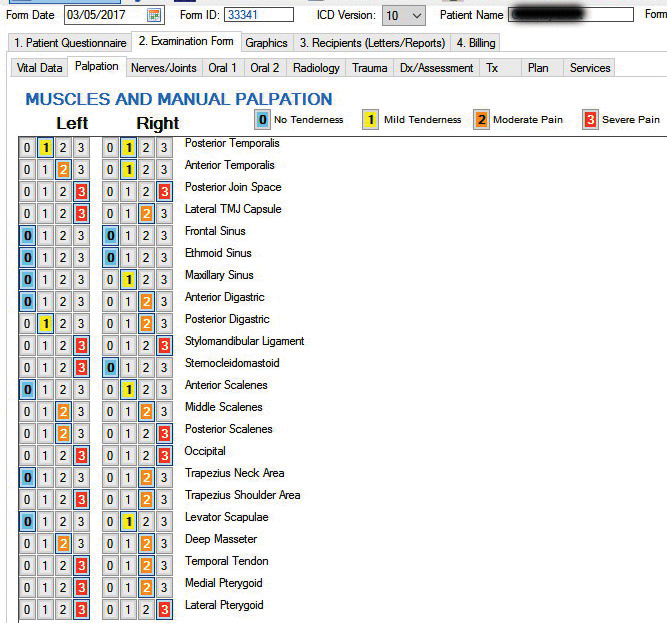

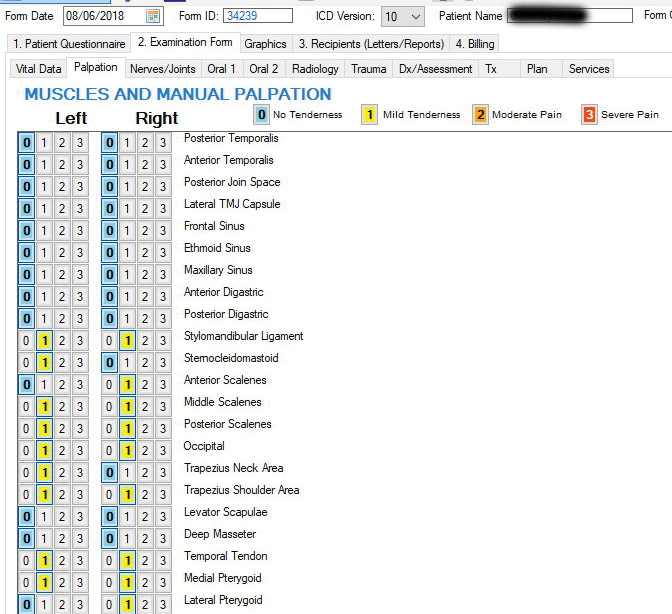

The initial temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD) evaluation is a thorough clinical examination to establish objective evidence of TMD. Since the mandible is functionally connected with the cervical spine,1,2 it is in fact cranio-cervical-mandibular dysfunction (CCMD). The evaluation includes mandibular range of motion; Doppler examination of the TMJs; evaluation of the upper cervical rotation; and palpations of the muscles and joints of the jaws, head, and neck (Figure 1). If such evidence of TMD/CCMD is present, is it related to the chief complaints and treatable nonsurgically? Lastly, does the TMD affect more than just the jaws, and if so, what is the magnitude of its impact on the entire body? Patients are accepted for treatment only if there is a high degree of confidence that we can help the patient resolve or significantly reduce the symptoms for the long term without relying on medications to manage symptoms.

Figure 1. Pretreatment palpation.

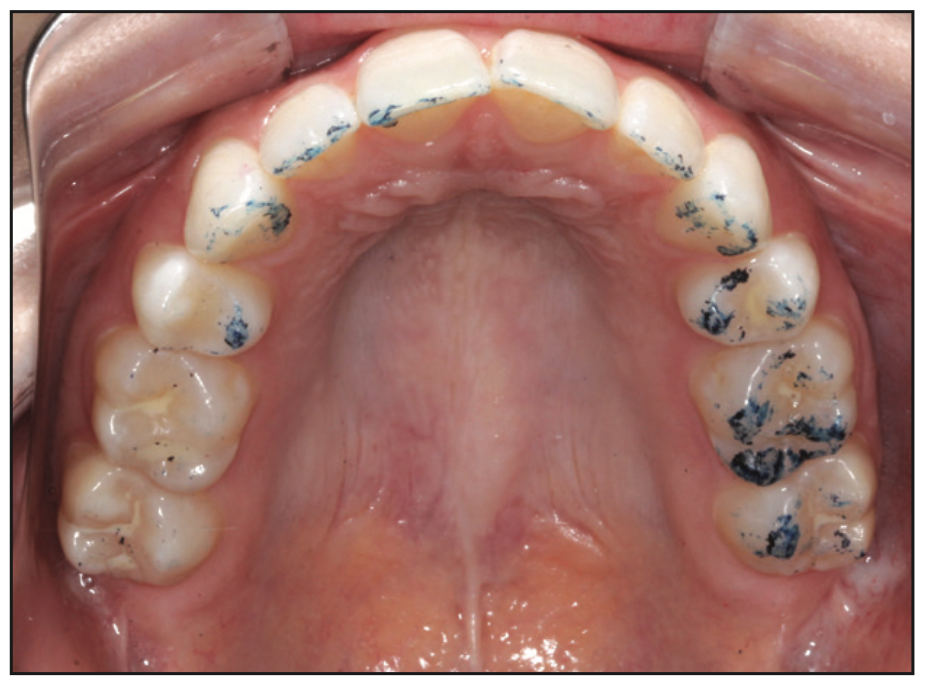

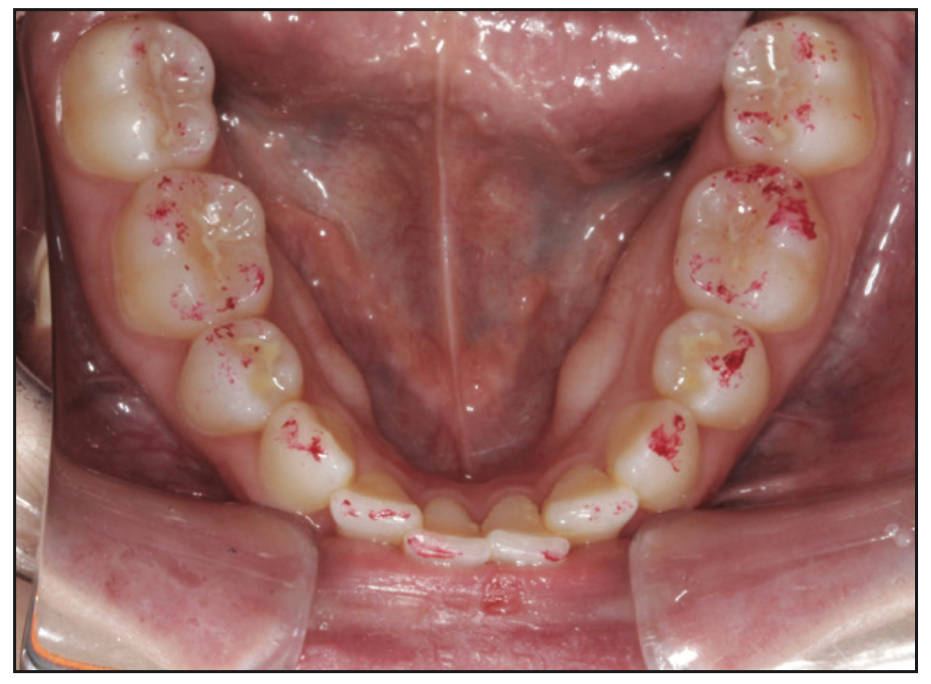

Suppose the patient wishes to proceed with treatment. In that case, the next step is a set of diagnostic tests to precisely diagnose the structural discrepancy between the mandible and maxilla, which necessitates the muscles of mastication and cervical posture to compensate to bring the teeth into occlusion. The terminal contact position of the teeth is the “presenting occlusion” (Figures 2 to 4). If occluding requires an increased effort of elevator muscles just to bring the teeth together, that taxes the patient’s adaptive capacity. Adaptive capacity varies due to a myriad of factors, including genetics; gender; prior injury or treatment; emotional factors, including post-traumatic stress disorders; and even cultural beliefs.3 When adaptive capacity is exceeded, symptoms ensue. Since many of these factors cannot be changed, it is pragmatic to focus on those that can be readily improved, starting with the structural discrepancy of the presenting occlusion vs the mandibular relation to maxilla when all the muscles of mastication and cervical posture are unstrained.

Figure 2. Presenting occlusion.

Figure 3. Maxillary arch with occlusal marks.

Figure 4. Mandibular arch with occlusal marks.

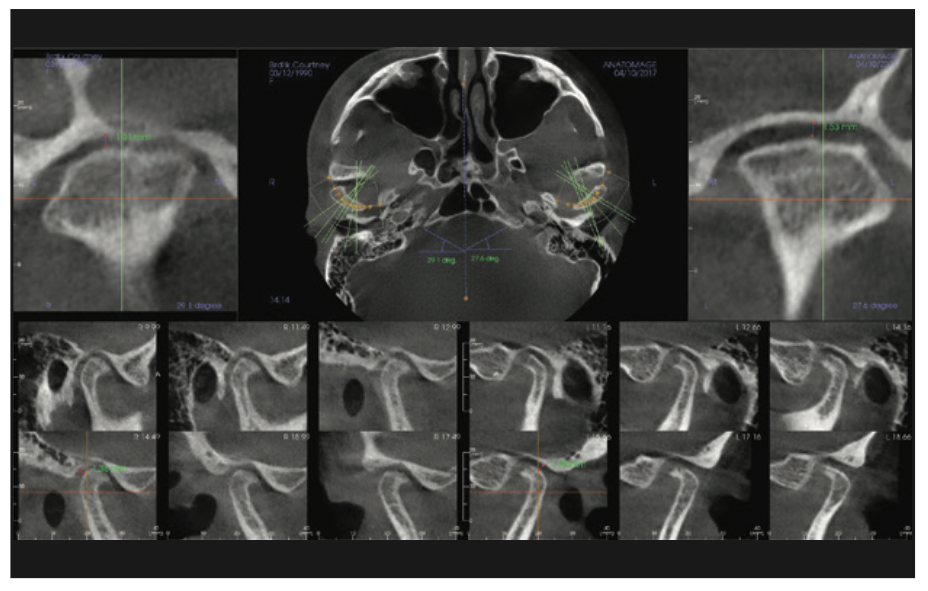

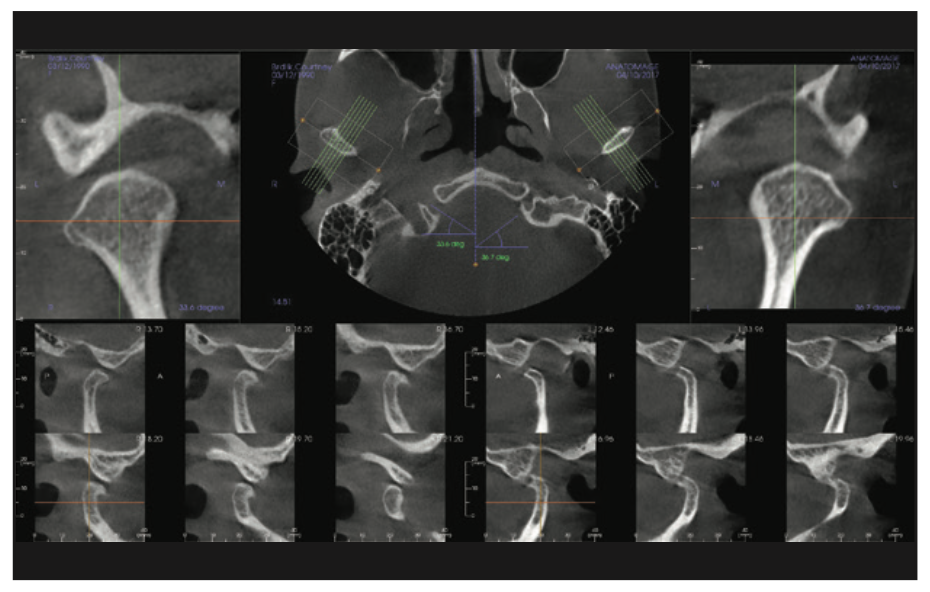

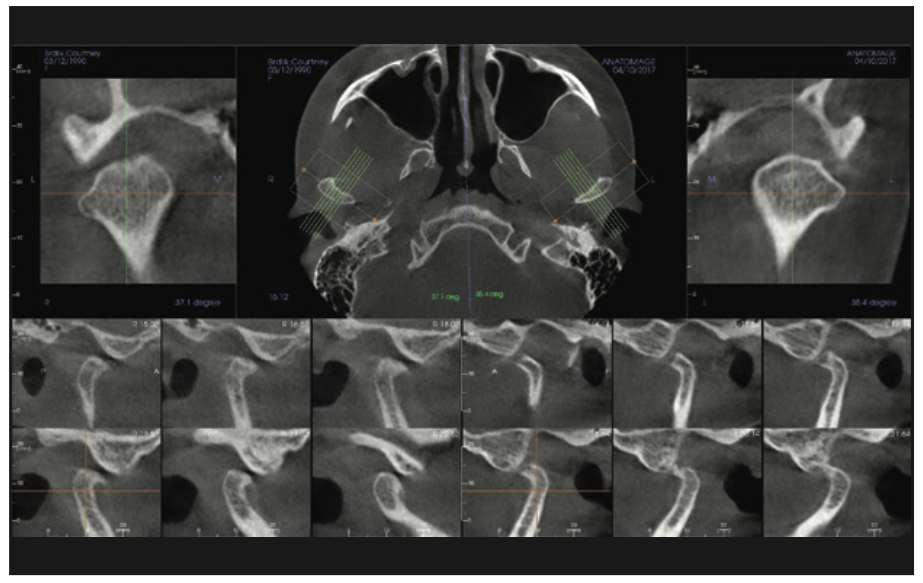

The diagnostic tests included CBCT scans of the jaws, head, and neck with teeth in presenting occlusion and with the mandible at maximum opening and in maximum protrusion (PaX-i3D [Vatech]). Analyses of these volumes were done to discern TMJ condition and position, the pharyngeal airway, and cervical alignment and rule out any tooth or bone pathology. The maximum-opening scan shows if the condyles are able to translate and if the condyles are subluxing past the eminence. The maximum-protrusion scan shows if there is condyle-to-fossa contact, which indicates a missing or highly degenerated articular disc, and if there is improvement in the pharyngeal airway (Figures 5 to 7).

Figure 5. TMJs at presenting occlusion.

Figure 6. TMJs at maximum opening.

Figure 7. TMJs at maximum protrusion.

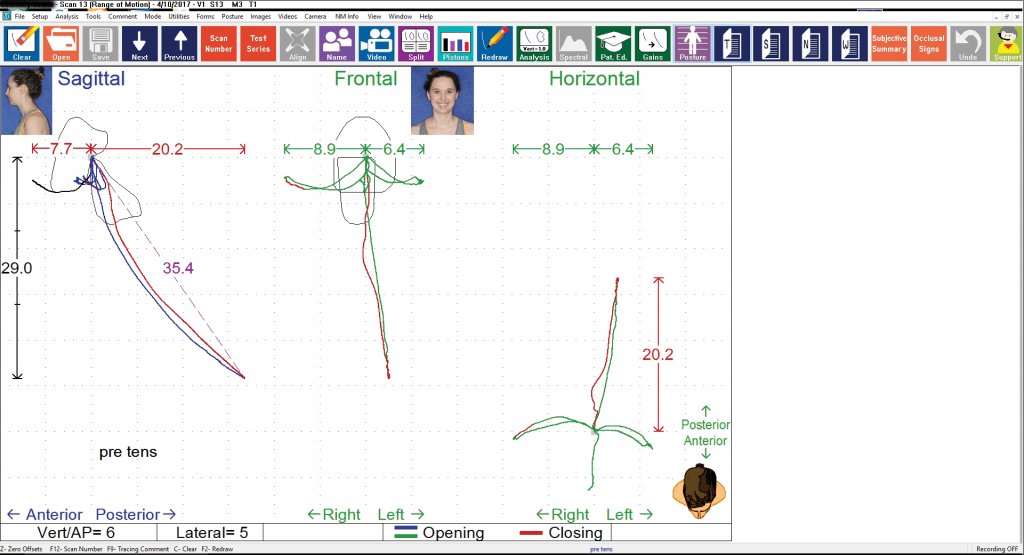

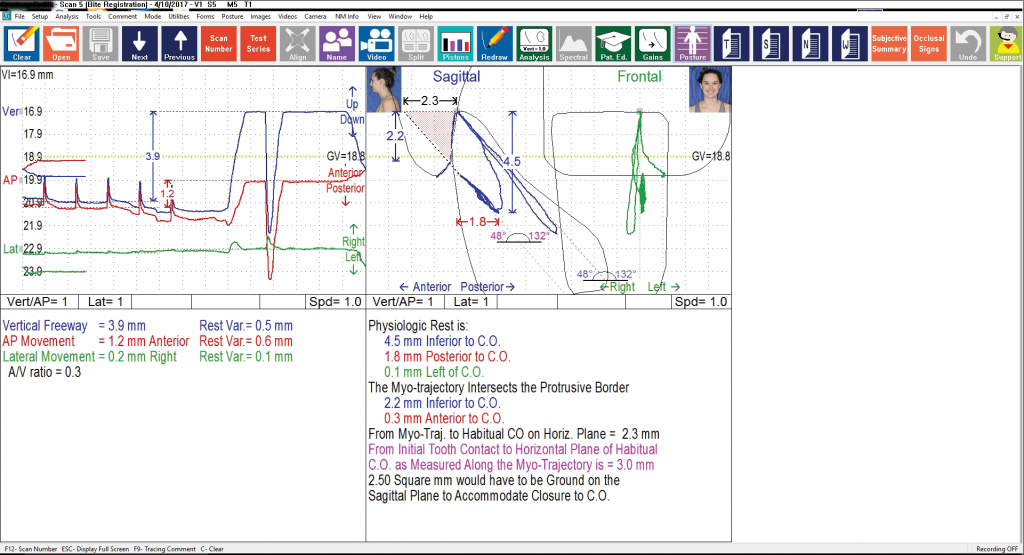

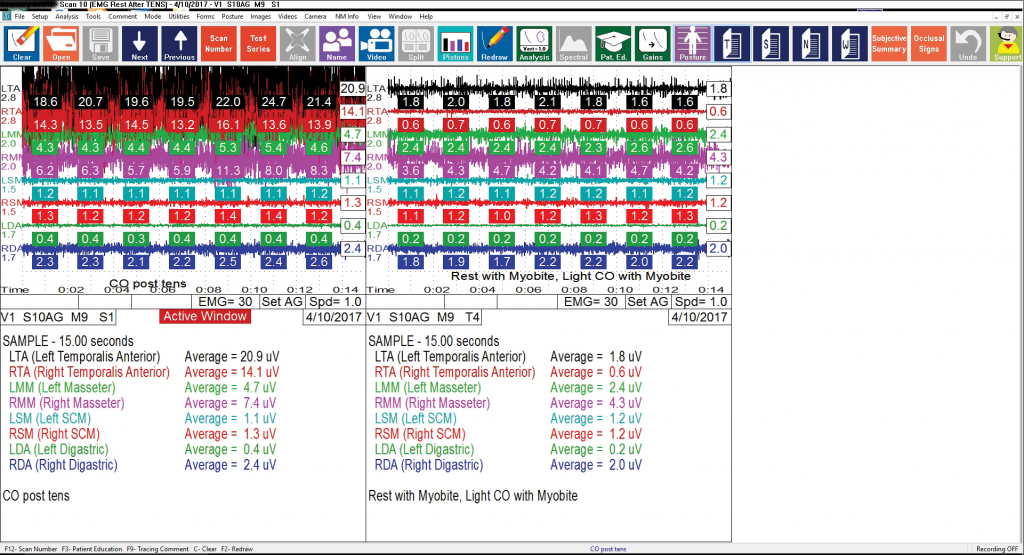

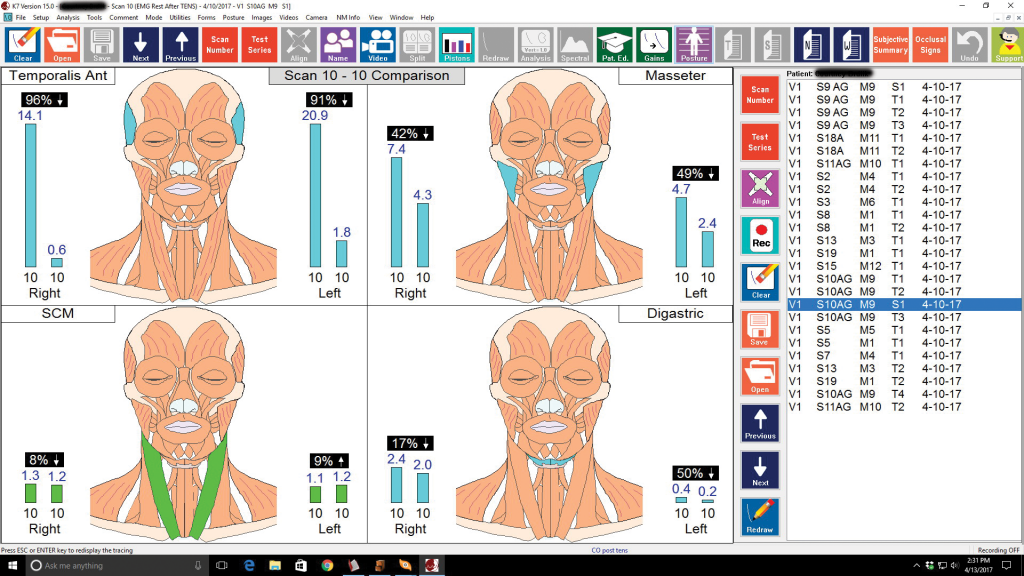

Multiple surface electromyography studies of the temporalis anterior and medial masseters give data on mandibular posture; sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and digastric anterior muscles give data on head/neck posture. Computerized mandibular scans provide data on jaw movement tracking, ROM, and velocity (Figure 8). Electrosonography scans give data on joint noises with the corresponding location on the opening/closing cycle (K7 computer system [Myotronics]).

Figure 8. Range of motion.

The use of ultra-low frequency (ULF) transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) at 0.66 Hz (J-5 Dental TENS [Myotronics]) of trigeminal and facial nerves at mandibular notches is the classic neuromuscular technique for relaxing jaw and facial muscles. ULF TENS stimulation of the spinal accessory nerve at the posterior cervical triangle, the “Prabu Point” technique,4 relaxes the SCMs, trapezius, and cervical muscles. During 60 minutes of ULF TENS therapy, moist heat packs applied to the neck and thoracic regions enhance muscle relaxation. Cranio-cervical physical therapy (per Dr. Mariano Rocabado) is used to optimize the alignment of the cervical vertebrae while the patient is practicing deep, slow, waveform breathing (pranayama). The above “Raman CCMD protocol,” when implemented at the dental chair for more than 70 minutes, has been predictably effective in achieving unstrained jaw and cervical musculature as well as optimized cervical vertebral alignment. This allows the determination of the precise mandibular position where the joints and muscles of mandibular and cervical posture would be unstrained (Figures 9 to 11).

Figure 9. Physiologic position.

Figure 10. Electromyography (EMG) presenting occlusion vs diagnosed position.

Figure 11. EMG shows 96% and 91% less effort to occlude at the diagnosed position.

The findings of these diagnostic tests were shared in detail with the patient so that she could make an informed decision on treatment. As a PharmD, she “knew” that chronic pain can only be managed. But she hoped to get at least a 40% improvement of symptoms, which set a benchmark for treatment success.

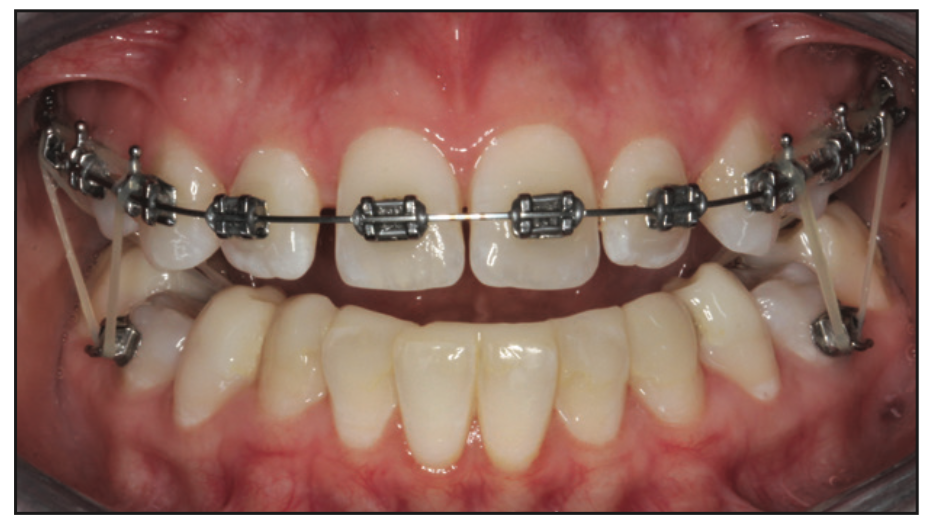

Consistent with the ADA TMD parameters of care,5 phase 1 treatment is reversible and would be done for a 90-day-maximum trial period. Only when there is a resolution of symptoms exceeding the benchmark set by the patient would any phase 2 option be considered. An anatomic, physiologic neuromuscular (PNM) fixed orthotic based on a laboratory-created wax-up to the diagnosed position and stent is built with dimethacrylate temporary material (Visalys Temp [Kettenbach LP]) and bonded to the mandibular teeth to correct the diagnosed discrepancy. These are aesthetic, seldom interfere with speech, and do not encroach on the room for the tongue. The patient functions full-time with the fixed orthotic to facilitate TMJ healing and resolve muscle dysfunction (Figure 12). During phase 1, supportive physical therapy is utilized to address postural dysfunction. When indicated, myofunctional therapy is used.

Figure 12. Phase 1 mandibular fixed orthotic.

The success of the orthotic therapy is measured subjectively, which is the relevant metric for the patient, and objectively since the clinician cannot know how the patient feels. These objective metrics include a post-orthotic CT scan to compare joint position, pharyngeal airway, and cervical posture; K7 jaw computer scans to measure jaw tracking, muscle function, and joint noise; measurements of C1-C2 rotation and muscle; and joint palpations.

The patient reported a 50% overall improvement of symptoms at 3 days post orthotic delivery. Jaw pain improved 75%. Upper back pain improved 25%. As a PharmD, she “knew” the pathophysiology of migraines and did not expect any changes from correcting the jaw alignment. But in 3 days, her migraines/headaches improved from severe to mild.

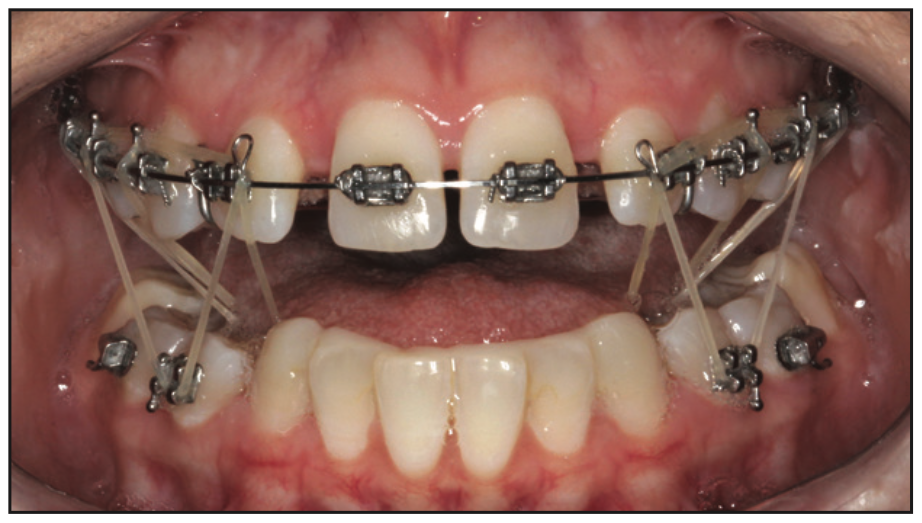

By 30 days, TMJ pain was 90% relieved. She could eat anything she wanted without pain. Neck pain was 90% relieved, and thoracic pain was 100% resolved. The patient did not need 90 days to judge the effectiveness of phase 1. She chose the neuromuscular functional orthodontics (NFO) option for arch correction to regain space and move the teeth into their diagnosed positions. By then, she was back in New Orleans. Even though it would require many flights over 3 years, she liked the idea of moving her own natural teeth to the optimal PNM position to support her optimal jaw/neck alignment for the long term. The maxillary form was corrected first to allow the mandible to optimally align while the fixed orthotic maintained the interarch alignment and supported the TMJs. She was informed that there would be spaces created as the arch form was corrected, since she was missing her first premolars, and that, if she wanted, she could have veneers to correct the spaces. Once the maxillary arch was corrected, part of the orthotic over the mandibular first molars was removed. Using elastics, those teeth, along with the supporting alveolar bone and gingival tissue, were verticalized to meet the maxillary teeth. The process was repeated for the premolars, then the anteriors, and finally the second molars (Figures 13 to 16). Once all of the mandibular teeth had been moved to occlude with maxillary teeth, the PNM CCMD treatment was completed. Throughout NFO treatment, progress was monitored through subjective and objective metrics (Figures 17 and 18).

Figure 13. Maxillary arch after development.

Figure 14. Mandibular first molar exposed.

Figure 15. Mandibular second premolar exposed.

Figure 16. Mandibular anteriors exposed.

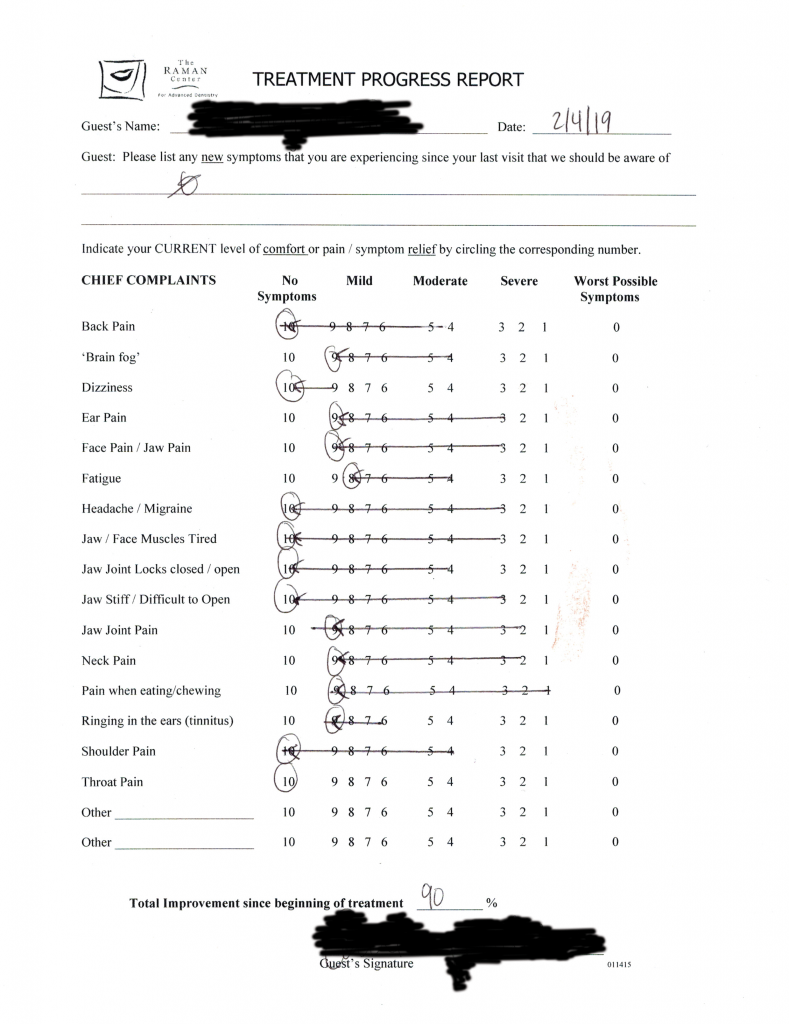

Figure 17. Post-treatment palpation.

Figure 18. Progress of symptoms vs pretreatment symptoms—comfort scale.

Figure 19. Completed treatment after veneers were placed.

The patient chose to have the spaces corrected with aesthetic veneers. That was completed in March 2019 (Figure 19). Nearly 3 years since the completion of her treatment, she continues to be free of TMJ pain, jaw pain, neck pain, thoracic pain, and migraines. In fact, she reports that she has not had one migraine attack since the day the fixed orthotic was delivered in May 2017.

In May 2016, a 39-year-old female trial attorney sought help for the inability to talk very long due to facial pain, limited mouth opening, and jaw pain with chewing. She had seen 4 dentists and had worn many mouthguards. She had undergone physical therapy for 8 months.

Reviewing her medical history revealed the following: migraines/headaches for 18 years that got progressively worse since 2014, for which she was treated by 4 neurologists. Up to 50 different medications (antidepressants, pain meds, and migraine meds), PT, chiropracty, and a cefaly device had not given lasting relief. She was taking up to 18 doses of Zomig per month as abortive medication. Basically, she “lost any hope of relief.” The patient also reported a 10-year history of neck pain and back pain.

The same protocol described earlier was followed in diagnosis and phase 1 and phase 2 treatment. Six weeks after starting phase 1 fixed orthotic, her headaches were 100% resolved. She used to get migraines daily, and after this course, did not have one in weeks. She got 80% resolution of neck pain and 90% resolution of pain when chewing. She chose to start with phase 2 NFO right away. NFO was completed in August 2020.

In March 2021, a 25-year-old male auto mechanic searched “TMJ” for his painful jaw popping. He was unable to tolerate his dentist-made nightguard due to gagging.

Reviewing his history revealed a 9-year history of bilateral HA at constant pain level of 5/10 that would flare up to 10 three times a month and a 2-year history of posterior neck pain at 6 to 7/10 that flared up to 10 every week despite getting chiropractic adjustments twice a week. He also suffered from facial twitches and anxiety. His C1-C2 rotation was 30° bilaterally. His palpation pain score was 82/132.

The same protocol was used for diagnosis and phase 1 PNM fixed orthotic treatment as in prior cases. One week post-PNM fixed orthotic, he reported a 95% improvement of symptoms as well as improvement with headaches (95%), jaw pain (100%), facial twitches (80%), and neck pain (100%). He never used to smile because he was in so much pain. His wife reported that he smiled a lot now. He was also sleeping through the night and felt more rested and energetic in the morning vs lying in bed for an hour before getting up. By 6 weeks, his palpation pain score was 2/132. C1-C2 rotation was 90 degrees bilaterally, and he reported 100% improvement of headaches as well as improvement in jaw pain (90%), facial twitches (50%), and neck pain (90%). He had not needed chiropractic adjustment even once since starting treatment. He chose the NFO option as his phase 2 treatment.

In June 2019, a 39-year-old female had a loud jaw pop while eating, followed by mandibular right side tooth pain and sensitivity. Her DDS noted asymmetrical opening and clicking and referred her to us for TMD evaluation.

Reviewing her medical history revealed the following: a lifetime of anxiety that was diagnosed as General Anxiety Disorder 17 years prior and for which she was put on SSRI medication. Even with Prozac 10 mg, she lived with 5/10 anxiety that spiked up to 7/10 daily and 10/10 three times monthly. She always woke up tired and felt constantly fatigued, feeling a constant pressure on her jaws and teeth at 4/10 as long as she was taking 400 mg of Ibuprofen every 6 hours; otherwise, it was 7/10. Despite taking Gabapentin 100 mg for 5 years, she had constant neck pain for 13 years at 3/10. She was getting chiropractic adjustment every 6 weeks when it peaked at 7/10.

The same protocol was used as in prior cases for diagnosis and phase 1 PNM fixed orthotic treatment.

By 6 weeks of phase 1 orthotic, there were symptom improvements in anxiety (75%), fatigue (40%), pressure in the jaw and teeth (100%), and neck pain (100%). C1-C2 rotation was 90° bilaterally vs zero degrees preoperatively. She has not seen the chiropractor at all since starting treatment. She also mentioned that she was less clumsy and felt more balanced. She chose a removable CAD/CAM orthotic and a mandibular repositing device for nighttime as her phase 2 option.

CONCLUSION

In closing, I hope that this case stimulates your curiosity when you encounter patients seeking answers for their TMD symptoms. What they reveal may simply be the tip of the iceberg of symptoms that are affecting their quality of life. They may also be “land mine” cases that become severely symptomatic even after routine dental treatment.

I look forward to your questions, thoughts, and comments.

REFERENCES

- de Wijer A, Steenks MH, de Leeuw JR, et al. Symptoms of the cervical spine in temporomandibular and cervical spine disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 1996;23(11):742–50. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2842.1996.d01-187.x

- Zafar H, Nordh E, Eriksson PO. Temporal coordination between mandibular and head-neck movements during jaw opening-closing tasks in man. Arch Oral Biol. 2000;45(8):675–82. doi:10.1016/s0003-9969(00)00032-7

- Maixner W, Diatchenko L, Dubner R, et al. Orofacial pain prospective evaluation and risk assessment study–the OPPERA study. J Pain. 2011;12(11 Suppl):T4-11.e1-2. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2011.08.002

- Raman P. Neurally mediated ULF-TENS to relax cervical and upper thoracic musculature as an aid to obtaining improved cervical posture and mandibular posture. Holleman SA Jr., ed. In: ICCMO Anthology IX. International College of Cranio-Mandibular Orthopedics; 2010:77-85.

- Flasko A, Patel H, Butchert A, et al. Managing TMD. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128(2):146–7. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0144

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Raman received his DDS degree from the University of Missouri, Kansas City School of Dentistry. His practice focuses exclusively on cranio-cervical-mandibular dysfunction/temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD), and dental sleep medicine. He is a clinical advocate and teaches TMD courses for Vivos Institute.

He has served as a clinical instructor and featured speaker on TMD for the Las Vegas Institute of Advanced Dental Studies. He lectures and teaches hands-on courses internationally.

He can be reached at dr@midwestheadaches.com.

Disclosure: Dr. Raman has received lecture honoraria from Myotronics, Vivos Therapeutics, MyoAligner, Kettenbach LP, BISCO, and Carestream Dental.