After measuring and analyzing aerosol generation during dental procedures, researchers at Imperial College London and King’s College London are suggesting changes that can prevent contamination and improve safety for dental patients and staff alike.

Dental procedures can pose a high risk of viral transmission because the tools they require often produce aerosols, which can include high numbers of SARS-CoV-2 virions, which are copies of the virus that causes COVID-19, the researchers said.

Aerosols are generated when saliva mixes with water and air streams used in dental procedures. Dental practices have had to introduce new room decontamination processes and personal protective equipment measures that have reduced the number of patients that can be treated in a single day.

In particular, the researchers said, long intervals can be required between dental treatments with rooms left unoccupied to allow aerosols to dissipate, limiting patient access and challenging financial feasibility for many dental practices worldwide.

The researchers now suggest avoiding the use of dental drills that use a mixture of air and water as abrasion coolants and carefully selecting and controlling drill rotation speeds for those instruments that only use water as a coolant.

Also, the researchers have identified parameters that would allow some procedures such as dental fillings to be provided while producing 60 times fewer aerosol droplets than conventional instrumentation.

“Aerosols are a known transmission route for the virus behind COVID-19, so, with our colleagues at King’s, we have tested suggested solutions that reduce the amount of aerosols produced in the first place. These could help reduce the risk of transmission during dental procedures,” said lead author Dr. Antonis Sergis of Imperial’s Department of Mechanical Engineering.

“This important work describes the basic mechanisms that lead to the features of dental aerosols that we currently consider to be high risk,” said coauthor Professor Owen Addison of King’s College London’s Faculty of Dentistry, Oral & Craniofacial Sciences.

“This has enabled us to choose drill parameters to keep our patients and the dental team safe at this difficult time. Although we cannot provide every procedure, because slowing our drills is much less efficient, we now have the basis to do more than we have done in the last six months,” Addison said.

The results of the study already are being included as evidence in guides for dental practices in the United Kingdom during the pandemic.

The researchers used dental clinical rooms at Guy’s Hospital in London to test how aerosols are generated during procedures such as decay removal, applying and polishing fillings, and adjusting prostheses. They measured the aerosol generation using high-speed cameras and lasers and used their findings to suggest modifications.

Air turbine drills, which are the most common type of dental drill, create dense clouds of aerosol droplets that spread as fast as 12 meters per second and can quickly contaminate an entire treatment room. Just one milliliter of saliva from infected patients includes up to 120 million copies of the virus, each with the capacity to infect.

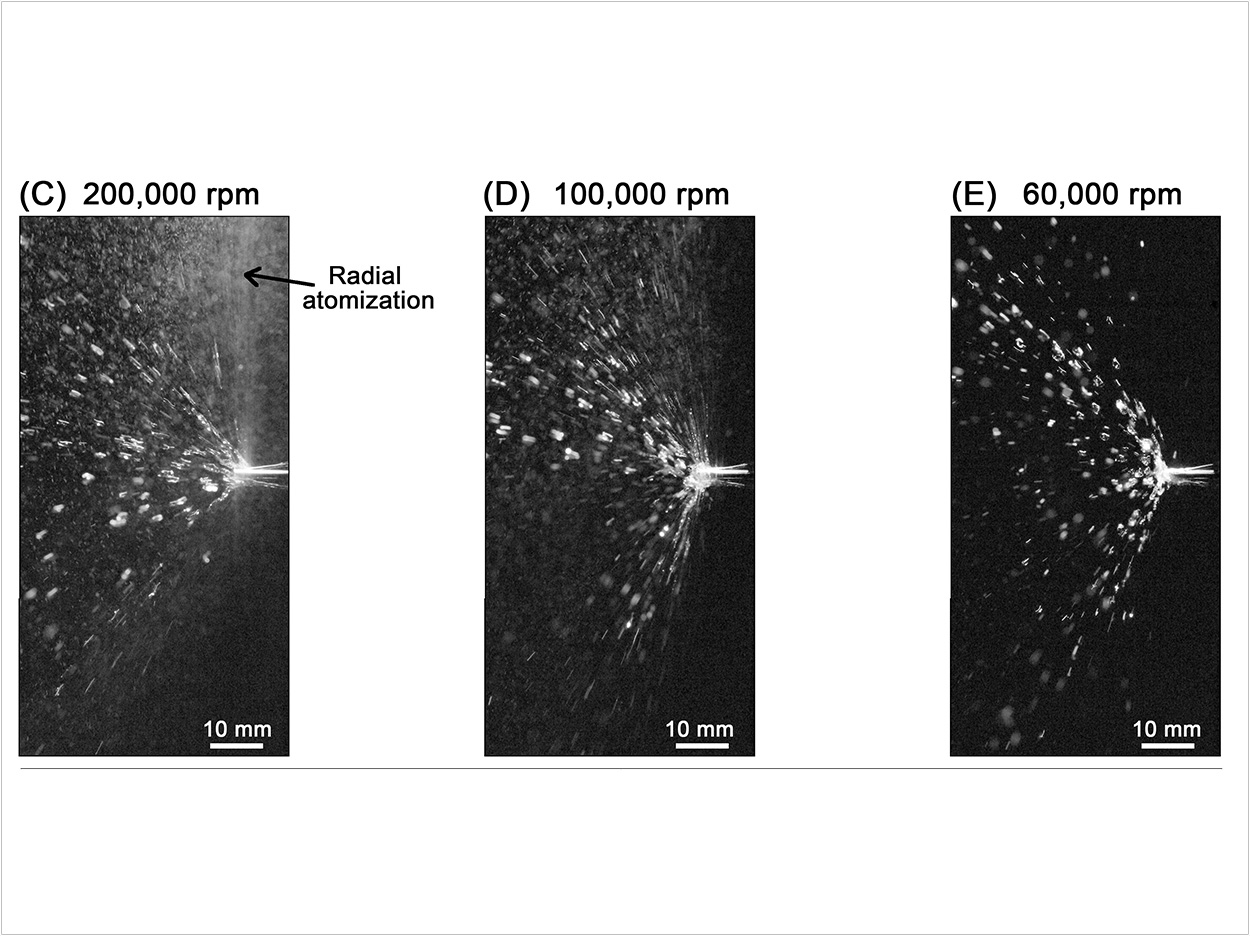

The researchers also tested high-torque electric micromotors with and without the use of water and air streams. They found that using this type of drill at low speeds of less than 100,000 rpm without air streams produced 60 times fewer droplets than air turbine drill types.

Additionally, the researchers found that aerosol concentration and spread within a room depends on the positioning of the patient, presence of ventilation systems, and the room’s size and geometry.

Concentration and spread also are influenced by the initial direction and speed of the aerosol itself, which can be affected by the type of cutting instrument (burr) and the amount and type of cooling water used.

By understanding how to reduce the amount of aerosol generated in the first place, the researchers said, their suggestions could help dentists practice more and help patients get the treatment they need.

The researchers also said that patients still should not attend dental appointments if they have symptoms of COVID-19.

“Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, dentistry has become a high-risk practice, but the need for treatments hasn’t gone away,” said Addison. “Our suggestions could help begin to open up dentistry to patients once again.”

The suggestions have been included in the evidence appraisal in dentistry document, “Rapid Review of Aerosol Generating Procedures in Dentistry,” published by the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme.

The results from the study also have been considered by an expert task force convened by the Faculty of General Dental Practice (UK) (FGDP(UK)) and the College of General Dentistry and published in their guide, “Implications of COVID-19 for the Safe Management of General Dental Practice.”

“The impact of the results is significant. For example, the risk categorization for dental procedures included in the FGDP(UK) document was certainly influenced by our work,” said coauthor Professor Yannis Hardalupas of Imperial’s Department of Mechanical Engineering.

The researchers’ work is ongoing. They are currently better assessing the risk of infection by quantifying the amount of saliva mixed into the generated aerosols by dental instruments.

The study, “Mechanisms of Atomization from Rotary Dental Instruments and Its Mitigation,” was published by the Journal of Dental Research.

Related Articles

CDC Infection Control Guidelines Catch Up With Need to Address Aerosols

Collaboration Launches Online Fallow Time Calculator

Study Analyzes Aerosol Exposure in Open-Layout Dental Offices