By Jerome P. Rothstein, DDS, MHA

Hundreds of thousands of patients receive cancer chemotherapy annually in the United States. All dental practices, including pediatric and orthodontic practices, have patients who have undergone, are undergoing, or will undergo cancer chemotherapy in the future. Cancer chemotherapy is changing rapidly, as established protocols evolve and are refined and new therapeutic approaches are introduced. This article discusses current concepts in medical oncology and cancer chemotherapy as they relate to oral healthcare.

Dental care is an important consideration for cancer chemotherapy patients for several reasons: (1) Chemotherapy patients who have excellent oral health are less likely to have severe complications from their cancer treatment than are patients in poor oral health; (2) Dental treatment before, during, and after cancer chemotherapy requires special considerations; and (3) Chemotherapeutic agents and coagents are associated with specific oral pathology.

Included among the current issues regarding oral manifestations of cancer chemotherapy are a possible relationship between the osteoclast inhibitors pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) and osseous necrosis of the jaws1; caution with regard to the daily use of chlorhexidine2; and the question of bacterial endocarditis (BE) prophylaxis for patients who have previously received cardiotoxic chemotherapy and/or left chest wall radiation therapy.3

CHEMOTHERAPY

Cancer chemotherapy is intended to delay or abort the proliferation of tumor masses or tumor cells. Most cancer chemotherapies attack tumors at the cellular level by directly damaging the DNA of the cancer cells, by stopping the replication of cancer cells via nucleotide blockade, or by halting cancer cell mitosis.4 Other therapies prevent the formation of new blood vessels, thus limiting the growth of certain solid tumors.5

Antineoplastic agents (chemotherapeutic agents) are employed as primary treatment agents, as adjuvant treatment, or as palliative medications. In such cancers as acute lymphoblastic leukemia, disseminated Hodgkin’s disease, choriocarcinoma, testicular carcinoma, or Ewing’s sarcoma, chemotherapy is the primary treatment. In certain tumors, such as some stages of breast, prostate, lung, or colon cancer, chemotherapy is employed adjuvantly with surgery and/or radiation therapy. In some cases, antineoplastic agents produce palliation and prolongation of life, but are not curative.

Other biological agents, such as antivirals and aromatase inhibitors, are prescription medications that treat side effects of chemotherapy or enhance the effects of antineoplastic treatments.

BONE MARROW TRANSPLANTATION

Bone marrow transplantation or peripheral blood stem cell transplantation are frequently employed in the treatment of certain cancers, enabling the application of much higher levels of radiation therapy and chemotherapy than were previously utilized. The method involves the application of cytotoxic doses of systemic radiotherapy or systemic chemotherapy that create profound myelosuppression, after which transplantation of healthy cells can rejuvenate the hematopoietic system. In addition, marrow from a donor other than the host may bestow an antitumor effect upon the host marrow.

ANTINEOPLASTIC AGENTS

Chemotherapeutic agents are classified according to their origins or biochemical actions. Alkaloids such as vinblastine, vincristine, and vinorelbine interrupt cell mitosis. Alkylating agents such as cisplatin, carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, and busulfan prevent DNA replication. Antimetabolites such as methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil, and cytosine arbinoside inhibit the production of enzymes needed for DNA and RNA synthesis. Antitumor antibiotics such as bleomycin, doxorubicin, idarubicin, mitomycin, dactinomycin, and plicamycin inhibit DNA and RNA synthesis by binding to DNA. Camptothecins such as topotecan and irinotecan inhibit the enzyme topoisomerase I, leading to breakage of DNA strands. Enzymes such as L-asparaginase prevent protein synthesis. Taxanes such as paclitaxel and docetaxel inhibit cell division. Other agents such as hydroxyurea and procarbazine attach to cancerous lymphocytes. Monoclonal antibodies such as trastuzumab and rituximab are created specifically to bind to cancer cells and/or to carry cytotoxic agents to those cancer cells. Aromatase inhib-itors such as anastrozole inhibit estrogen production.

EFFECTS OF CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY ON NONMALIGNANT AND MALIGNANT CELLS

A major goal of cancer chemotherapy is to target cancer cells without damaging normal cells. However, antineoplastic medications can affect both nonmalignant, rapidly dividing cells and malignant cells. Currently, most agents affect normal cells as well as tumor cells. Many chemotherapeutic agents decrease the growth rate of cancer cells and simultaneously affect normal, rapidly dividing cells of the bone marrow, skin (hair follicles), and gastrointestinal tract.

These effects on normal cells can cause important clinical symptoms. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and stomatitis may occur due to sloughing of the gastrointestinal mucosa. Hair loss, dermatitis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome may arise as cutaneous manifestations of chemotherapy. Anemia or thrombocytopenia may follow bone marrow suppression. Jaundice, ileus, convulsions, or neuropathies (including phantom toothaches) may result from hepatic dysfunction. Hyperuricemia may be a consequence of renal involvement. A markedly increased susceptibility to all types of infections may result from suppression of the immune system.

EFFECTS OF CHEMOTHERAPY ON THE ORAL CAVITY

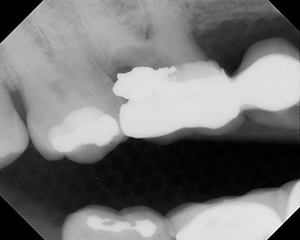

A number of antineoplastic agents are stomatotoxic; ie, contribute to significant clinical oral side effects. Among those side effects are xerostomia, dysgeusia, tooth sensitivity (phantom toothaches), gingival hemorrhage, mucosal ulcerations, hemorrhagic mucositis, and herpetic, bacterial, or fungal infections (Figures 1 to 4).

|

|

| Figure 1. Hemorrhagic mucositis, as observed in some chemotherapy patients. | Figure 2. Panoral mucositis, secondary to cancer chemotherapy. |

|

|

| Figure 3. Candidiasis (moniliasis, thrush), secondary to cancer chemotherapy. | Figure 4. Viral lesions, as observed in some chemotherapy patients. |

Significant oral and systemic disability may occur secondary to stomatotoxicity. In addition to severe, continuous pain, patients may be unable to eat and may experience fever.

Mucositis of the mouth and oropharynx may become so severe that the oral intake of food is impossible. Such severe mucositis is frequently observed when concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy are employed, for example, in the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma.6 Nutritional support may require the use of a feeding tube, such as a percutaneous epigastric tube, during and after therapy.

While most chemotherapy agents may produce some mucositis, this side effect is particularly associated with certain drugs. Among the agents known to be severely stomatotoxic are actinomycin D, amsacrin, bleomycin, chlorambucil, cisplatin, cytarabine, daunorubicin, docetaxel, doxorubicin, etoposide, floxirodom, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, mitoxantron, plicamycin, thioguanin, vinblastine, and vindesine.7

DENTAL EVALUATION PRIOR TO CHEMOTHERAPY

The main oral complications and adverse sequelae of chemotherapy relate to conditions such as pre-existing intrabony pathology, necrotic teeth, advanced periodontal disease, and chemotherapy-induced mucositis. Indeed, oral infection from abscessed teeth, intrabony pathology such as cysts, or advanced generalized periodontal disease may produce life-threatening infections and fevers in patients as they undergo chemotherapy. Such infections may necessitate an interruption of the chemotherapy treatment, and therefore can compromise the outcome of cancer treatment.

Chemotherapy-related mucositis is the patchy sloughing of the lining of the mouth, resulting in easily infected open mucosal wounds. Bacterial, viral, and/or fungal infections may ensue. Painful, infected, generalized mucosal wounds may cause interruption of the planned chemotherapy or may result in systemic infections.

The purpose of the dental evaluation prior to chemo-therapy is to identify existing or potential oral infection. Oral infection control should be instituted prior to the initiation of chemotherapy. In this manner, the patient’s ability to tolerate chemotherapy may be greatly enhanced. Furthermore, excellent oral health has been consistently shown to improve the general comfort of chemotherapy patients, and, most importantly, to result in fewer interruptions of chemotherapy treatment.8 Conversely, generalized poor oral health contributes to episodic fevers-of-unknown-origin during chemotherapy, interrupting or aborting the cancer chemo-therapy.

The dental evaluation and preventive treatment regimen should include the following:

(1) panoramic radiograph to disclose bone pathology for both edentulous and dentate patients;

(2) full-series dental radiographs for dentate patients;

(3) periodontal examination and charting;

(4) control of gross periodontal pathology;

(5) removal of nonrestorable teeth;

(6) temporary or permanent repair of restorable carious teeth;

(7) elimination of periapical pathology;

(8) dental prophylaxis, fluoride application, and construction of custom, flexible topical fluoride trays for patient home care; and

(9) detailed home care instructions and prescription of daily topical 0.4% stannous fluoride or 1.1% sodium fluoride.

ORAL CARE DURING CHEMOTHERAPY

Patients who are undergoing cancer chemotherapy should be given detailed home care instructions:

(1)Patients who have prostheses should at least once daily remove partial or complete dentures from the mouth.

(2)Use a denture brush, baking soda, and water to clean the dentures.

(3)Soak the dentures for 30 minutes in an antifungal and antibacterial solution and then thoroughly rinse with water.

(4)Leave dentures out of the mouth during sleep or when irritations develop.

(5)Floss the natural teeth by gently placing dental floss between the teeth and sliding the floss up and down each side of each tooth.

(6)Brush the teeth with a soft toothbrush using toothpaste or baking soda.

(7)Place 0.4% stannous fluoride or 1.1% sodium fluoride on the natural teeth for 5 minutes every night using a flexible fluoride carrier or a toothbrush. After applying fluoride, do not rinse the mouth, eat, or drink for 30 minutes.

(8)Use chlorhexidine spar-ingly, if at all.

(9)Avoid alcohol-based mouthrinses.

(10)Do not use toothpicks.

(11) Avoid abrasive foods.

DENTAL TREATMENT DURING CHEMOTHERAPY

During chemotherapy, patients often will have a compromised immune system, so a dental infection or treatment could have serious consequences. Therefore, prior to any dental treatment, the medical oncologist should be consulted. On a positive note, patients who are brought to excellent oral health and who are frequently seen by a dentist during the sequence of chemotherapy have a better clinical course during this treatment.9

Certain dental treatments require specific precautions:

Prophylaxis and periodontal therapy should ideally be provided prior to the institution of chemotherapy or after completion of cancer therapy. For leukemia patients, periodontal therapy should be reserved until the disease appears to be in remission.

Periapical pathology should be eliminated, if time allows, prior to chemotherapy. Nec-rotic teeth and some vital teeth may be endodontically treated even during chemo-therapy if the following conditions exist:

(1)an atraumatic technique is employed;

(2) the coagulation status is known and allows tissue manipulation;

(3)the white blood cell count is known to be satisfactory; and

(4)the medical oncologist approves of the endodontic therapy.

Endodontic treatment should include the following:

(1)atraumatic rubber dam clamp placement (possibly using surface grooving of the treated tooth for clamp retention);

(2) gentle intracanal instrumentation short of the apex;

(3)cautious injection of local anesthetics;

(4) possibly avoiding local anesthetic if the pulp is necrotic; and

(5)possibly mummifying vital pulps for a week prior to final extirpation.

Operative dentistry should be completed prior to beginning chemotherapy, with temporary or permanent restorations of large carious lesions given priority. Routine operative procedures (local anesthesia, nitrous oxide, oral sedation, rubber dam placement, and matrix band placement) could produce serious complications if the patient receiving chemotherapy is immunocompromised.

Tooth extractions should be completed prior to initiation of chemotherapy. Based upon the patient’s coagulation status, the medical oncologist may determine how soon chemotherapy may commence after extractions. For patients who have begun chemotherapy, and extractions are absolutely necessary, gentle tissue management, appropriate suturing, and local hemorrhage control are indicated. Prior to extractions, the coagulation status of the patient (INR, partial thromboplastin time, platelet count, and bleeding time) should be assessed. When an extraction is required during chemotherapy, a platelet count of less than 40,000 mm3 may indicate the need for a preoperative platelet transfusion. A granulocyte count of less than 2,000 mm3 may indicate the need for preoperative antibiotic coverage. Chemotherapy is commonly suspended until the dentist and the medical oncologist determine that the patient’s coagulation status is satisfactory for dental extractions. Healing extractions sites are observed by the dentist for at least 3 postoperative days. If blood clot formation and healing are satisfactory, the medical oncologist may then elect to resume chemotherapy.

Prostheses (removable) should be relieved of all severe undercuts or sharp ridges, then highly polished and cleansed with an ultrasonic cleaner. An overnight soak of the dentures each night in an antifungal solution can be helpful. A clotrimazole solution may be used to cleanse dentures in cases of clinical candidiasis.

Antibiotic therapy may be required in immunocompromised patients who present with an oral infection. However, the possibility of inducing a superinfection should be considered when prescribing antibiotics for the chemotherapy patient.10 Consultation between the medical oncologist and the dentist is advisable.

Any patient with an indwelling catheter should be considered for antibiotic prophylaxis prior to invasive dental procedures.

VASCULAR ACCESS DEVICES

Vascular access devices or central venous catheters are catheters inserted into major central veins or peripheral veins to facilitate repeated administration of fluids, medications, blood products, chemotherapy, or parenteral nutrition. These central lines may also be used to draw blood samples and for hemodialysis. The major types of central lines include peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC lines), implanted portals, nontunneled catheters, and tunneled catheters. Patients under-going cancer chemotherapy may also have a vascular ac-cess device, the presence of which may be an indication for antibiotic prophylaxis.

ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS

Invasive dental procedures may induce bacteremias in which oral organisms infect the tissue surrounding an implanted device or a heart valve. Patients who have vascular access devices, those who have received cardiotoxic cancer chemotherapy, and those who have had radiation therapy to the left breast and chest, are each at increased risk for valvular heart disease. The dentist should advise the patient’s medical oncologist prior to performing invasive dental procedures. If antibiotic prophylaxis is advised, it is common to use the American Heart Association guidelines used for bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis.11

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN CHEMOTHERAPEUTIC AGENTS AND OTHER MEDICATIONS

Avoid the concurrent use of aspirin and methotrexate, as the pharmacologic and toxic effects of methotrexate may be magnified. Bleomycin therapy may result in pulmonary complications that preclude the use of inhalation agents such as nitrous oxide/oxygen or 100% oxygen.

OrAL PATHOLOGY AND PRESCRIBED MEDICATIONS SUCH AS BISPHOSPHONATES AND CORTICOSTEROIDS

Patients who have advanced breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, head and neck carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, multiple myeloma, or some forms of lymphoma may develop systemic hypercalcemia. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronic acid (Zometa) are bone resorption-inhibiting bisphosphonates that reduce hypercalcemia by restraining osteoclastic activity. Marx12 associates these 2 medications with painful bone exposures in the mandible, maxilla, or both that were unresponsive to surgical or medical treatments. Thirty-six cases were observed, of which 28 were initiated by tooth removal, resulting in bone exposures mostly on the lingual surface of the posterior mandible. Marx further notes that other bisphosphonates such as risedronate (Actonel), etidronate (Didronel), and tiludronate (Skelid) have not been associated with osseous necrosis of the jaws. The manufacturers of pamidronate and zoledronic acid initially did not recognize a causal relationship between these bisphosphonates and jaw necrosis.13 However, extreme caution is recommended when considering dental extractions, periodontal surgery, or dental implants in patients who are receiving pamidronate or zoledronic acid since the reported cases of necrosis have proven refractory to commonly employed treatments for osteonecrosis.

A relationship between avascular necrosis of bone and the use of glucocortico-steroids is much more widely recognized in the medical and dental literature. Numerous observers have documented necroses of various bony sites in patients receiving steroids such as dexamethasone.14 Other authors have associated specific cytotoxic medications, such as paclitaxel (Taxol) and docetaxel (Taxotere),15 with necrosis of the jaws and long bones.16 Additionally, osteoradionecrosis secondary to ionizing radiation is a well-recognized entity.17

CHLORHEXIDINE

For many years, dentists have prescribed 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinses as an aid in controlling plaque accumulation and periodontal disease. The frequent use of chlorhexidine has also been recommended for patients undergoing head and neck radiation therapy or systemic cancer chemotherapy.18 The use of chlorhexidine, however, is not recommended for prolonged use in these patients. First, in randomized studies, chlorhexidine was no more successful in preventing chemotherapy-induced mucositis than sterile water19 or a mouth-rinse of one-half teaspoon of salt and one-half teaspoon of baking soda in 8 ounces of water.20 Second, chlorhexidine may precipitate the emergence of Gram-negative bacilli infections in the oropharynx.21 Third, the commercial preparations of chlorhexidine contain alcohol, which induces marked discomfort in patients who have mucositis (nonalcohol chlorhexidine mouthrinses may be compounded by a pharmacist). Fourth, chlorhexidine may interfere with nystatin preparations during antifungal (candidiasis) treatment.22 Therefore, the routine use of chlorhexidine during cancer chemotherapy or radiation therapy should be avoided.

CONCLUSION

This article has reviewed current concepts in cancer chemotherapy as they relate to the oral care of cancer patients. Guidelines for the dental evaluation and care of chemotherapy patients are presented. Specific precautions for various dental treatments that may be required during cancer chemo-therapy are outlined. Information regarding the oral care of patients receiving bisphosphonates, the use of antibiotic prophylaxis for specific patients, and the use of chlorhexidine is offered. The intent of this article is to improve the oral healthcare of the growing number of patients who are undergoing cancer chemotherapy.

References

1. Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: a review of 63 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:527-534.

2. Foote RL, Loprinzi CL, Frank AR, et al. Randomized trial of a chlorhexidine mouthwash for alleviation of radiation-induced mucositis. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2630-2633.

3. Gonzaga AT, Antunes MJ. Post-radiation valvular and coronary artery disease. J Heart Valve Dis. 1997;6:219-221.

4. Krakoff IH. Cancer chemotherapeutic and biologic agents. CA Cancer J Clin. 1991;41:264-278.

5. Giles FJ. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling pathway: a therapeutic target in patients with hematologic malignancies. Oncologist. 2001;6(suppl 5):32-39.

6. Okita J, et al. Concurrent chemo-radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2004;31:43-47.

7. Kostler WJ, et al. Oral mucositis complicating chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy: options for prevention and treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:290-315.

8. Chambers MS, Toth BB, Martin JW, et al. Oral and dental management of the cancer patient: prevention and treatment of complications. Support Care Cancer. 1995;3:168-175.

9. Sonis S, Kunz A. Impact of improved dental services on the frequency of oral complications of cancer therapy for patients with non-head-and-neck malignancies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;65:19-22.

10. Emmanouilides C, Glaspy J. Opportunistic infections in oncologic patients. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1996;10:841-860.

11. Dajani AS, Taubert KA, Wilson W, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommendations by the American Heart Association. Circulation. 1997;96:358-366.

12. Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic [letter]. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1115-1117.

13. Tarassoff P, Csermak K. Avascular necrosis of the jaws: risk factors in metastatic cancer patients [letter]. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1238-1239.

14. Gebhard KL, Maibach HI. Relationship between systemic corticosteroids and osteonecrosis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:377-388.

15. Wang J, Goodger NM, Pogrel MA. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with cancer chemotherapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1104-1107.

16. Marymont JV, Kaufman EE. Osteonecrosis of bone associated with combination chemotherapy without corticosteroids. Clin Orthop. 1986;204:150-153.

17. Jereczek-Fossa BA, Orecchia R. Radiotherapy-induced mandibular bone complications. Cancer Treat Rev. 2002;28:65-74.

18. Ferretti GA, et al. Chlorhexidine prophylaxis for chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced stomatitis: a randomized double-blind trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:331-338.

19. Dodd MJ, Larson PJ, Dibble SL, et al. Randomized clinical trial of chlorhexidine versus placebo for prevention of oral mucositis in patients receiving chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1996;23:921-927.

20. Dodd MJ, Dibble SL, Miaskowski C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of 3 commonly used mouthwashes to treat chemotherapy-induced mucositis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:39-47.

21. Raybould TP, Carpenter AD, Ferretti GA, et al. Emergence of gram-negative bacilli in the mouths of bone marrow transplant recipients using chlorhexidine mouthrinse. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1994;21:691-696.

22. Barkvoll P, Attramadal A. Effect of nystatin and chlorhexidine digluconate on Candida albicans. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:279-281.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to thank Marjorie A. Rothstein, RN, and Thomas A. Marsland, MD, for reviewing this manuscript.

Dr. Rothstein is a diplomate of the American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and maintains a private practice at 943 Cesery Boulevard, Jacksonville, Fl, 32211. He can be reached at (904) 743-5604 or marjerry2@bellsouth.net.