It has long been thought that our genomes may play a role in determining the risk of tooth decay.1 But recent data from the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) suggests otherwise.2

Andres Gomez and his coauthors studied 485 twin pairs (both fraternal and identical), aged 5 to 11 years, to examine the relationship between host genetics and the oral microbiome in the context of health and disease.

Despite a strong genetic influence on oral microbiome composition, they discovered that environmental factors (fermentable carbohydrate consumption and oral hygiene patterns) were the stronger drivers of cariogenic oral microflora.2

So, while some of our patients may blame their own poor oral health on family history, they won’t be able to do so for much longer. It’s more likely that inadequate oral hygiene behaviors and diet are key in determining their risk.2

Around the world, eating behaviors have evolved. Three meals a day is no longer standard. Our hectic lifestyles have ushered in a new era of on-the-go eating.3 Food is offered everywhere, which is probably why we now graze throughout the day.

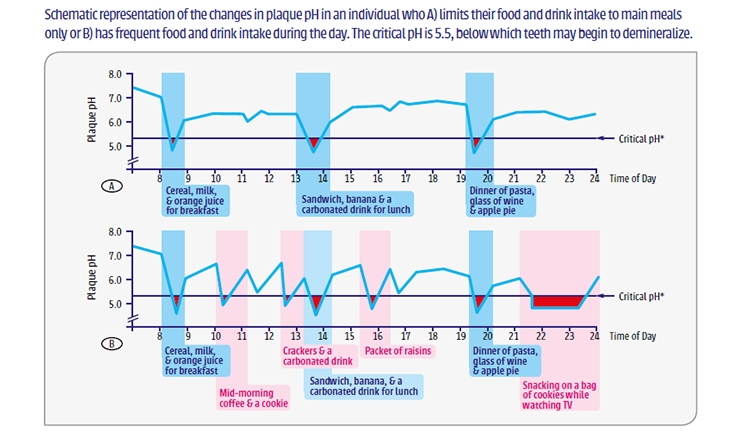

On average, people now eat or drink on five separate occasions every day.4 This increased frequency of eating cariogenic food opens up a can of oral health worms, potentially increasing the incidence of dental caries as a result of the continual plunges in plaque pH.5,6

It has been suggested that caries can develop with more than six exposures to fermentable carbohydrates per day, even with regular fluoride use.7 As such, Philip Marsh, PhD, professor of oral microbiology at the University of Leeds School of Dentistry, has advocated an ecological approach to managing caries by regular interventions that help maintain a symbiotic oral microbiome.8

It’s true that most of us still brush twice a day,9 which is great because this is what most dental associations still recommend.10 But our oral health should be going mobile as our eating habits go mobile.

It’s as if our eating behavior has evolved along with the Digital Age, but our oral hygiene behaviors are stuck in the Stone Age. Remarkably, though tooth decay is largely preventable, it remains the most common chronic disease in the world.11

We need to extend our oral care practices beyond the bathroom. Brushing, though important, is not enough! This will give everyone more opportunities to manage oral hygiene during the day.

It’s dentists and dental staff who are the gatekeepers to good oral health. So, knowing that nurture beats nature when it comes to oral health, what can we do, right now, to help our patients stay free from decay?

We can share knowledge and make positive oral health discussions a standard part of our oral health consultations.

We can remind patients to brush twice and floss daily and invite them for regular checkups—a chance to re‑remind them about all of these points!

We can encourage our patients to eat a healthy diet that’s less acidogenic and hence less likely to decrease oral and plaque pH.

We can recommend chewing sugar‑free gum throughout the day. Extensive research shows sugar-free gum will stimulate saliva production, helping to neutralize plaque acid and regulate oral pH.3,12 It’s also known to strengthen teeth, so it should form part of the oral hygiene routine.3

Despite the known benefits, not all oral care guidelines mention sugar-free gum. It’s imperative that organizations and oral care guidelines go further to encourage people to adapt their oral hygiene behavior and protect their teeth on the go, every time they eat or drink.

References

- Bretz WA, Corby P, Schork N, et al. Evidence of a contribution of genetic factors to dental caries risk. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2003;3:185-189.

- Gomez A, Espinoza JL, Harkins DM, et al. Host genetic control of the oral microbiome in health and disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:269-278.e3.

- Wrigley Oral Healthcare Program. Sugar-free chewing gum in oral health: a clinical overview. April 2015. http://www.wrigleyoralcare.com/content/docs/WOHP_Clinical_Booklet.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- Special Eurobarometer 330. Oral health. http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/archives/ebs/ebs_330_en.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- Euromonitor International. Home cooking and eating habits: global survey strategic analysis. April 30, 2012. http://blog.euromonitor.com/2012/04/home-cooking-and-eating-habits-global-survey-strategic-analysis.html. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- Hornick B. Diet and nutrition implications for oral health. J Dent Hyg. 2002;76:67-78.

- Philip N, Suneja B, Walsh LJ. Ecological approaches to dental caries prevention: paradigm shift or shibboleth? Caries Res. 2018;52:153-165.

- Marsh PD. In sickness and in health—What does the oral microbiome mean to us? An ecological perspective. Adv Dent Res. 2018;29:60-65.

- Delta Dental of Illinois. 2017 Oral health and well-being survey. http://oralhealthillinois.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/2017-Adult-Oral-Health-Survey-Brochure.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- American Dental Association. ADA statement on regular brushing and flossing to help prevent oral infections. https://www.ada.org/en/press-room/news-releases/2013-archive/august/american-dental-association-statement-on-regular-brushing-and-flossing-to-help-prevent-oral. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. J Dent Res. 2013;92:592-597.

- Dodds MW. The oral health benefits of chewing gum. J Ir Dent Assoc. 2012;58:253-261.

Dr. Dodds is senior principal and lead oral health scientist at Mars Wrigley Confectionery in Chicago. He works with the Wrigley Oral Health Program (WOHP), which supports dental care professionals in educating individuals about maintaining a healthy lifestyle and reducing tooth decay. He joined Wrigley in 2002 after 15 years in academic dentistry and is adjunct faculty at the UIC College of Dentistry, Chicago. He holds a dental degree from the University of Edinburgh and a PhD in dental science from the University of Liverpool, and he has published more than 60 peer-reviewed papers, book chapters, and articles. He can be reached at michael.dodds@effem.com or at linkedin.com/in/michael-dodds-7655203/.

Related Articles

Sugar-Free Gum Could Save $4.1 Billion in Dental Costs

Oral Health Guidelines Not Enough for Today’s “Grazing” Culture

Chewing Gum Detects Inflammatory Bacteria