Americans say they can’t live without them. What could they be talking about in the modern era of the 21st century? Could it be a mobile phone? A car? A computer? No…it is something as simple as a toothbrush. An MIT survey in January of 2003 reported that adults and teens think the toothbrush is the number one invention.1 That list included the automobile and cell phone, personal computers, and microwave ovens. Without question, Americans value their toothbrushes.

A BRIEF HISTORY

The Babylonians chewed on primitive toothpicks to clean their teeth.2 As years passed, the toothpicks evolved into the chew stick, which was the size of a modern pencil. One end of the stick was chewed and became soft and brush-like, while the opposite end was pointed and used as a pick to clean food and debris from between the teeth. These implements resembled what we know today as the “Perio-Aid.” The twigs used as chew sticks were selected from aromatic trees that had the natural ability to clean teeth and freshen the mouth. The earliest literature making reference to these twigs is found in China at approximately 1600 BC; these chew sticks may have even had a religious significance. The ancient Chinese said that 15 minutes of tooth-brushing could equal 70 prayers.

The first bristled toothbrush originated in China at around 1600 AD. Handles were carved out of cattle bone; natural bristles were placed in holes bored in the bone and kept in place by thin wire staples. Natural bristles were obtained from the necks and shoulders of swine, especially from pigs living in areas with colder climates such as Siberia and China.

By the early 1800s, bristled brushes were in general use in Europe and Japan. In 1844, Dr. Meyer L. Rhein patented and began manufacturing by hand a 3-row brush of serrated bristles. In 1857, H. N. Wadsworth was credited as the first American to receive a toothbrush patent. In 1885, the Florence Manufacturing Company of Massachusetts, in association with Dr. Rhein, began mass-marketing the Prophylactic brush, with wooden handles and natural bristles.

EVOLUTION OF THE TOOTHBRUSH

As technology progressed, wood and then plastic replaced bone handles, and synthetic bristles replaced natural bristles.3 Nylon was first applied to the toothbrush around 1937, and by 1938 Du Pont made the first soft nylon bristle brush. This nylon allowed the bristles on a toothbrush to dry quickly and not harbor bacteria to the extent of earlier technology.

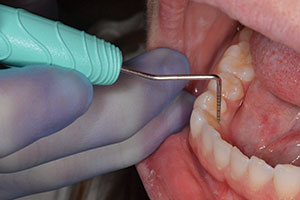

Dr. Charles C. Bass, a physician and dean of Tulane University Medical School, began studying dental diseases upon his retirement in 1940 (Figure 1).4 He substantiated the theory that oral hygiene was related to dental caries and periodontal disease. Dr. Bass also designed the “Right Kind Sub-G Ultra Soft” toothbrush and gave Sunstar Butler exclusive rights to market it. The product is still offered today (Figure 2).

|

|

| Figure 1. Dr. Charles Bass. | Figure 2. Modified Bass Technique using the Right Kind Sub-G Ultra Soft manufactured by Sunstar Bulter. |

WHERE ARE WE TODAY?

Toothbrush sales in the United States totaled more than $800 million in 2003. Companies have spent over $50 million just to advertise a new toothbrush in order to gain growing consumer market share and increase sales; at present, there is no end in sight. Thousands of different toothbrush variations have been developed and are continuously being developed by major companies. Toothbrushes come in many shapes, from curved to squiggled models. Multicolored, multi-angled, flexible, rippled, compact heads, and full, youth, and child sizes have now been developed. Even yearly awards are given for the best brush design.

A good toothbrush is relatively inexpensive compared to most dental procedures. Sales are bolstered by advertising claims and the seemingly endless variety of toothbrush shapes, styles, and colors marketed today. With so much product diversification, how can we educate our patients to choose the right toothbrush for themselves?

BRISTLE CHOICE

Choosing the best toothbrush begins with choosing the right bristles. Bristles are vital because they directly contact the teeth and gum tissue. Choosing the correct bristles is a valuable “insurance policy” against gum disease and tooth decay. Patients should consider bristle type, shape, and arrangement before purchasing any toothbrush.

Today, bristles are made of nylon and/or polyester. Toothbrush manufacturers are even adding rubber bristles. Mentadent introduced the White and Clean Toothbrush, which has a rubber strip in the middle of the rows of nylon bristles (Figure 3). This is said to help remove stains just as the windshield wipers on our cars remove the raindrops. Other toothbrush manufacturers have begun to place rubber bristles on the outside of the nylon bristles to help remove plaque and aid in stimulating the gum tissue. We have certainly advanced since the earlier times when chew sticks were used to clean teeth!

|

| Figure 3. Mentadent White and Clean. |

Hard-, medium-, and soft-bristled toothbrushes all remove plaque; however, hard and medium bristles can cause irreversible damage to the gums, tongue, and cheeks. They can also lead to periodontal disease and receding gumlines. Some types of resin-based dental restorations can be damaged by hard bristles. Studies show that soft-bristled toothbrushes remove plaque as effectively as medium or hard bristles. For these reasons, you should always advise patients to use a soft-bristled toothbrush.

Bristle Shape

The shape of the bristle tip is also important. Toothbrush bristles with sharp edges (also known as burrs) are more destructive to oral tissues than end-rounded bristles. It is difficult to see end-rounded bristles on a toothbrush because they are so small. Crest Complete toothbrushes have end-rounded bristles, as do Colgate, Oral-B, and Sunstar Butler (Figures 4 and 5). The soft-bristled brushes that are ADA approved are end-rounded. End-rounding removes the burrs, which can cause a brush to be abrasive (Figure 6). The Sunstar Butler Micro Tip toothbrush has bristles that are 400 times smaller than other soft, 0.008 bristles.

|

|

| Figure 4. Crest Massage Plus. | Figure 5. Reach Max. |

|

|---|

| Figure 6. End-rounding removes burrs caused by bristle trimming. |

Splayed bristles lose cleaning efficiency, serve as an indication of brushing with too much pressure, and should be immediately replaced (Figure 7).

|

| Figure 7. Worn bristles. (Toothbrush photos courtesy of Art Womack, DDS.) |

Bristle Arrangement

Clumps of toothbrush bristles are called tufts. Toothbrushes range from 15 to 45 tufts and are arranged in 2, 3, or 4 rows. More tufts increase the size of the toothbrush head, which makes it more difficult to clean the posterior teeth. Multitufted brushes usually offer assorted bristle sizes and shapes, and are engineered for better cleaning.

THE OBJECTIVE OF TOOTHBRUSHING

There is one simple objective of tooth brushing: to remove the plaque and biofilm that cause tooth decay and periodontal disease.5 Recently, research has proven that biofilm causes a variety of damage. When biofilm is left behind in the oral cavity, it becomes slimy and changes the consistency of bacteria and plaque colonies.

When is the Best Time to Brush?

It is important to have patients go to sleep with a clean mouth because the bacterial plaque or so-called biofilm tends to multiply in a dry environment. At night, our biological systems slow down. Not only does our heart and breathing slow down, but the oral cavity has reduced saliva flow. For those who sleep with an open mouth or who are mouth breathers in general—beware!

Thorough Removal of Plaque and Biofilm

It is not only the bristle type that is important but also the mechanical action provided by the toothbrush and the individual holding it. Plaque is a sticky substance, and the texture or type of plaque varies from one person to the next. Considering this information, the amount of brushing time depends on the type of plaque in an individual’s mouth. Power brushes have timers on them, which can indicate when a specific amount of time has elapsed. One person can remove all the plaque from his or her mouth in less than 2 minutes, while someone else may need to spend more than 2 minutes to remove plaque adequately. What we need is a timer that is specific for each individual.

The dental hygiene appointment is an excellent time to evaluate the virulence of a patient’s plaque and decide how much time is adequate to remove plaque efficiently and effectively. When the hygienist is able to spend 5 minutes of the hygiene appointment teaching or reviewing the importance of good oral hygiene, future dental appointments can become easier. When patients understand how to clean their mouths effectively and feel motivated to continue good home care, they will reap the benefits not only financially, but will receive better dental reports at future appointments.

Modified Bass Technique

Most dental professionals have learned the Bass technique as an effective way to remove plaque. Knowing the most recent information about biofilm means that our patients also need to remove plaque from other areas of the oral cavity. The Modified Bass technique cleans and massages the gingival areas of the mouth (Figure 2). And don’t forget to recommend cleaning the tongue!

Indications to Change a Toothbrush

Oral B has a toothbrush known as The Indicator. It has a blue dye that fades after numerous uses. When the blue is no longer present, people then know it is time to buy a new toothbrush. Usually toothbrushes wear out after 6 to 8 weeks of regular use. Patients should also be informed to change them if they have been sick, even with just a minor sore throat. Patients should not wait until the bristles no longer stand up straight to change to a new toothbrush.

CONCLUSION

A multitufted toothbrush with soft, end-rounded bristles is best. Tooth-brushing needs to be specific for each individual, depending upon his or her needs, in order to be effective. Factors to consider when giving oral hygiene instructions should include the shape of an individual’s teeth, a review of medications, and the patient’s manual dexterity, tooth morphology, age (small children need help from their parents because of undeveloped manual dexterity), diet, virulence of plaque, acidity and flow of saliva, susceptibility to decay, lifestyle, and even motivation.

No one can be forced to maintain good oral health, but if open-ended questions are asked, patients may have a more positive attitude toward compliance. It is best to recommend toothbrushes with the ADA Seal of Acceptance. This indicates that the brush has met or exceeded specific quality standards and is safe and effective to use. Brushing technique, brushing frequency, diet, and many other factors also influence plaque accumulation.

For patients wanting to simplify their life, it is not necessary to buy the latest in technology. Manual toothbrushes are low in cost and provide an effective way to keep teeth and gums healthy.

References

1. Lemelson-MIT Invention Index Survey. Toothbrush beats out PC, car, cell phone as the invention most Americans say they cannot live without. Available at: http://web.mit.edu/invent/n-pressreleases/n-press-03index.html#top. Accessed: January 2003.

2. Kepps SG. History of toothpicks. J Am Dent Assoc. 1945;33(5):284. Available at: oralb.com/learningcenter/teaching/history.asp. Accessed: March 8, 2004.

3. Panati C. The Modern Inventions of Our Time. 1st ed. London, England: Penguin Books; 1996.

4. Sunstar Butler. Product: GUM. Available at: http://www.jbutler.com/history_page.asp. Accessed January 17, 2004.

5. The Center For Biofilm Engineering at Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana. Movie Description: Liquid Flow Through Biofilm Channels. Available at: http://www.erc.montana.edu. Accessed January 20, 2004.

Ms. Seidel-Bittke is president of Dental Practice Solutions. She is also an author, international speaker, and dental practice management consultant specializing in nonsurgical preventive and periodontal treatment. Ms. Seidel-Bittke has extensive experience as a dental hygiene clinician, having worked in numerous private practices where she stressed comprehensive, nonsurgical periodontal treatment. She is a former clinical assistant professor at the University of Southern California and is currently a guest lecturer for the Contemporary Practice Management course at USC. She has been an active member of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association for more than 20 years. She can be reached at (866) 206-6364, debra@dentalpracticesolutions.com, or visit dentalpracticesolutions.com.