|

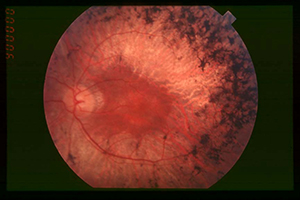

When crocodiles tried to be mammals: the Cretaceous crocodilan Pakasuchus kapilimai, complete with complex, mammal-like dentition and an unusually flexible spine, hunts dragonflies on an ancient Tanzanian floodplain. |

Paleontologists scouring a river bank in Tanzania have unearthed a previously unknown crocodile from 105 million-year-old, mid-Cretaceous rock in the Great East African Rift System.

The discovery of the relatively lanky, cat-sized animal with mammal-like teeth and a land-based lifestyle supports a growing consensus that crocodiles were once far more diverse than they are today, dominating ecological niches in the Southern Hemisphere during the Cretaceous Period that were filled in the Northern Hemisphere by early mammals.

An international team of researchers led by Patrick O’Connor of Ohio University describes the new animal in the Aug. 5 issue of Nature.

“At first glance, this croc is trying very hard to be a mammal,” O’Connor said. While numerous character traits show the animal is clearly crocodylian, he added, “A number of characteristics of this new species—including a reduction in its total number of teeth and a dentition specialized into ones similar to canines, premolars and occluding molars—are very similar to features that were critical during the course of mammalian evolution from the Mesozoic into the Cenozoic.”

The researchers have dubbed the new animal Pakasuchus kapilimai. Paka is Ki-Swahili for cat, in reference to the animal’s short, low skull with slicing, molar-like teeth, and souchos is from the ancient Greek for crocodile. The species name kapilimai is in honour of the late professor Saidi Kapilima of the University of Dar es Salaam, a key contributor to the NSF-supported Rukwa Rift Basin Project that led the discovery.

Despite features in Pakasuchus that are unusual for crocodylians, including an extremely flexible backbone, it clearly is a crocodile—right down to the trademark openings in its skull and the bony plates on its back and tail.

The plates are much less pronounced around the animal’s back and sides, perhaps allowing greater mobility, but it is the unusual dentition that is the most revealing difference. According to collaborator Nancy Stevens, also of Ohio University, the pivotal features distinguishing Pakasuchus from other crocodylians of the time, and since, is the complexity and differentiation in the teeth.

The high degree of fit between the upper and lower rear teeth suggest that, “This small-bodied animal occupied a dramatically different feeding niche than do modern crocodylians,” said Stevens. The teeth suggest an ability to process food in a manner that current crocodylians, with their bite and swallow tactics, lack—yet it is an ability virtually all mammals possess.

The fossil skull was originally encased in hard, red sandstone, and the jaws were tightly closed, so the paleontologists looked to a medical scanning technology called X-ray computed tomography to reveal details of the teeth and skull.

“This is a good example of how a tool generally associated with medicine and materials science has allowed examination of previously inaccessible paleontological samples,” said Paul Filmer, an NSF program director for sedimentary geology and paleobiology who has supported O’Connor’s research. “The research was conducted to such a degree of accuracy that the complexity and mechanics of food processing could be modeled.”

Despite the rock matrix, the researchers were able to create detailed digital images of the teeth accurate to 45 micrometers (millionths of a meter). Because the images were digital, they were ideal for animation, enabling the researchers to observe how the teeth fit with one another and estimate how the jaw may have moved.

The researchers looked at the entire skeleton, however, and based on a phylogenetic analysis of 236 characters, O’Connor and his colleagues placed Pakasuchus into an extinct crocodile group called the notosuchians.

With unusually mammal-like features, the notosuchians appear to have filled a range of ecological niches in the Cretaceous Period, a time when the continents of today were still separating out of the unified landmass of Pangea into somewhat smaller supercontinents including Laurasia in the north and Gondwanaland in the south.

|

The ancient crocodile Pakasuchus kapilimai once roamed the Middle Cretaceous of Tanzania. No larger than a house cat, the animal had a number of features unusual for crocodylians, including mammal-like teeth. |

“The research demonstrates that ecological niches have always been highly varied through Earth’s history,” Filmer said. “They are often filled by surprising branches like the notosuchians.”

Notosuchian diversity peaked across Gondwana during the Middle and Late Cretaceous, as the supercontinent fragmented into the southern continents of today—Afro-Arabia, Indo-Madagascar, Antarctica, Australia and South America.

“The presence of morphologically bizarre and highly specialized notosuchian crocodyliforms like Pakasuchus in the southern landmasses, along with an apparently low diversity of mammals in the same areas, has potentially profound ecological implications,” said collaborator Joseph Sertich of Stony Brook University. “This entire group of crocodiles deviates radically from the ‘typical’ crocodile, most notably in their bizarre dentitions, demonstrating a diversification not seen in the Northern Hemisphere during this time interval.”

The researchers are following their current work with a more detailed study of Pakasuchus, developing models of potential jaw movements and tooth-tooth interactions in a range of notosuchians.

“One of the most interesting aspects of a discovery like this is considering how such teeth develop in a crocodyliform,” O’Connor said. “Based on our current appreciation of tooth development in living crocodiles, notosuchians must have significantly altered developmental programs related to tooth shape, tooth number and tooth replacement patterns. This gives us a number of interesting evolutionary-developmental research questions to begin addressing using living crocodiles as models.”

The research team is also currently studying a number of other fossils recently uncovered in southwestern Tanzania. Included among the Cretaceous animals are dinosaurs, different types of crocodiles and mammals. The team has also recently uncovered a new fauna from the end of the Oligocene Epoch. These discoveries provide a glimpse of animals inhabiting mainland Africa just prior to the great faunal exchange with animals from Eurasia.

Collaborators on the study include Nancy Stevens and Ryan Ridgely of Ohio University; Joseph Sertich of Stony Brook University; Eric Roberts of James Cook University; Michael Gottfried of Michigan State University; Tobin Hieronymus of the Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine; Zubair Jinnah of the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa; Sifa Ngasala of Michigan State University and the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania; and Jesuit Temba of the Tanzanian Antiquities Unit. In addition to support from the National Science Foundation, the research was also supported by the National Geographic Society, the University of the Witwatersrand, the Michigan State University Office of Research and Graduate Studies, and the Ohio University’s College of Osteopathic Medicine and

Office of Research and Sponsored Programs.

Principal Investigator: Patrick O’Connor, Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine (740) 593-2110 OCONNORP@oucom.ohiou.edu.

|