In the field of oral aesthetics, the final vision should be perceived before treatment techniques commence. The final vision or perception is tempered with several technical factors. One is the vision of the practitioner, which could be influenced by the individual’s desires, the culture where he or she practices, or the availability of materials. For this author, however, the greatest limitation is the emotional imagination. Yet, this can also be turned around to be aesthetic dentistry’s greatest asset.

In aesthetic dentistry, we should see the desired result before we commence. Patients’ input is vital, and as we listen to them, we note these concerns and desires first. While they are not always practical, the patient’s desires are tempered by cultural, family, and economic influences. The dentist’s professional input should be combined with the patient’s desires. The dentist’s input is tempered by (1) experience, (2) educational exposure (how many continuing education courses have assisted his or her growth, confidence, experience, and comfort using available materials), (3) laboratory technique interchange, and (4) communication with labs. So many variables. We are in need of consistency with such variability.

Coordinating the periodontium and its colors and shapes1-4 to emphasize the teeth and desired smile using available restorative materials is technically paramount. Plus, imagination is needed. The preventive maintenance of the treatment result is also part of picture.

The natural color of the patient’s surrounding periodontal tissue should blend into and direct one’s focus to the desired aesthetic illusion. In other words, the background elucidates the foreground “illusion.” If the periodontal background is unhealthy or asymmetrical in height and/or length, it will distract from the desired focus.2,3,5 The periodontal tissues that form the background can and should be manipulated to gain health as well as a symmetrical background color. This may minimize or even avoid unnecessary mechanical correction of the hard tooth structures.

We need to know the desired anatomy before initiating treatment plus the effort it takes to achieve it. In the periodontal oral tissues, there are 2 colors that stand out—the reddish-blue alveolar mucosa and the pinkish-white keratinized attached gingiva.2,6,7 The line of demarcation is the mucogingival junction. If we can acquire a symmetrical healthy zone of attached gingiva around the teeth, we can accentuate desired aesthetic features and diminish undesirable ones more easily yet facilitate and maintain the results.

This article will emphasize the possibilities of aesthetics enhanced with periodontal techniques to gain tomorrow’s oral dreams today.

CASE 1

|

| Figure 1. Labial view. Note square-appearing incisors. The laterals’ gingival cervical level is asymmetrical; the centrals’ gingival cervical height is lower than the laterals. |

This is a case presentation of aesthetic periodontal therapy that minimizes restorative needs. Miss T, a 19-year-old female, presented with inflamed, bleeding gingiva and an “average” smile that concerned her cosmetically and socially. To improve her smile initially, nonsurgical scaling and curettage coupled with good oral hygiene were accomplished (Figure 1). The signs and symptoms of bleeding were resolved, but there was no “glow” in her smile, to use the patient’s words.

|

| Figure 2. Growing enamel technique. Notice the preservation of the interproximal tissue and the amount of enamel of the natural tooth now seen. The keratinized gingiva is preserved and positioned at the desired height. |

Treatment choices by restorative colleagues ranged from veneers to porcelain jackets to several crowns. Working with her restorative dentist and with consent from the patient, we changed her tissue background with the growing enamel technique1,4,8-10 (Figure 2). This technique does not expose the alveolar bone but rather changes the position of the desired tissue, with its desired color, to a healthier level and exposes the full shape, size, and aesthetic form of the teeth. Restoratively, all that was needed to achieve that desired appearance was a composite restoration on tooth No. 7.

|

| Figure 3. Healed tissue 2 months later. Note symmetrical level of pink attached gingiva leading toward visual goal. Shape and size of teeth are no longer square. New composite restoration is on tooth No. 7. |

As we see in Figure 3, the results are cosmetically exciting for the patient as well as the practitioners. We visualized the ending before proceeding. Choosing the easiest path to its goal, the clinical team made the path easier and more predictable.

CASE 2

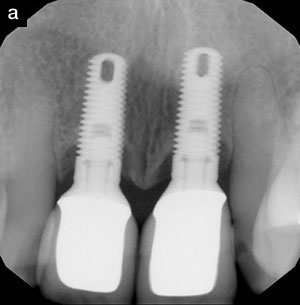

|

| Figure 4. Labial view showing worn bonding, square-appearing anterior teeth, uneven incisal edges, repair of chip incisally, and spacing between teeth. Uneven gingival-cervical line anterior/posterior. |

The desired goal in this case required (from a restorative standpoint) the use of veneers with their attendant mechanical advantages.12-14 The patient had existing bonded restorations on his maxillary anterior teeth, with some chipped edges, discoloration, undesired spacing, and square-appearing anterior teeth (Figure 4). The average length of a maxillary central incisor crown is 11.3 mm, and the M-D width is 9 mm. The average maxillary lateral incisor crown length is 10.1 mm, and 7 mm M-D width, which does not result in the “square” appearance as presented in this case.

|

| Figure 5. Cosmetic periodontal surgical techniques placing correct tissue on a horizontal symmetrical level and positioning the tissue at the desired height, exposing desired shape of teeth and repositioning frenum. |

|

| Figure 6. Periodontal tissue healed with a symmetrical zone of pink attached gingiva as a healthy background and new height of the teeth in preparation for veneers. Note the cervical lines on teeth Nos. 7, 10, and 11, where the change of the length of the teeth is obvious. |

|

| Figure 7. Final restorative result. Note the even shape and length of teeth. There are no longer spaces between teeth or chipped teeth, and there is a bright appearance. The background of a healthy symmetrical zone of attached gingiva enhances the symmetrical symbiotic relationship. |

The treatment consisted of initial periodontal therapy. Nonsurgical treatment with correct oral hygiene therapy was to be followed by periodontal surgery. A combination of the apically repositioned flap11 and the growing enamel1,8 technique as seen in Figure 5 allowed for the teeth to appear longer and streamlined compared to the square, shorter initial appearance. The horizontal symmetry of the pinkish-white healthy keratinized attached gingiva served as the background for the desired smile (Figure 6). The restorative dentist then completed the laminate veneer technique (Figure 7).

CASE 3

|

| Figure 8. Labial view of mandibular anteriors. Gingival colors are different and irregular, tissue is inflamed and bleeds, and there is no symmetrical zone of pink attached gingiva. There is a high frenum pull on the interproximal papilla between teeth Nos. 24 and 25. Teeth Nos. 23 and 26 appear short and square, and the centrals have an irregular appearance. |

In some cases, the desired goal may be achieved by using periodontal therapy or restorative treatment alone. Goals can be attained in many ways as long as the result is visualized before treatment commences. The approach should not be “Let’s do this and see what we’ll come up with.” There are colleagues to ask, articles and books to read and refer to, patients to listen to, and imagination to conjure all before one starts. In this case, the labial view of the mandibular anterior teeth is seen in Figure 8. Initially, we see irregular-sized teeth drawing unwanted attention to the area. The gingiva bleeds when brushed. The lateral incisors appear short and dwarfed by the canines and central incisors, and they appear almost one half the size of the adjacent teeth. The background periodontal tissues are irregular and different in color. For example, the gingiva of the mandibular right lateral incisor appears to have a deep red color that draws attention. The central incisors have irregular-appearing, inadequate zones of attached gingiva with a high pulling frenum.

|

| Figure 9. Cosmetic periodontal surgery, double sliding lateral gingival grafts, plus a frenectomy help achieve desired results. |

The goal for this patient is to make the area appear clean and healthy and not draw attention. There is no caries, so no mechanical changes were imperative. Using combinations of gingival grafts and variations of the lateral pedicle sliding gingival grafts2,15,16 in conjunction with a frenectomy, the periodontal surgery was completed. The technique utilized 2 double lateral sliding grafts. The gingival grafts were released and shifted mesially. The central incisor as well as the lateral incisor end with keratinized gingiva covering the labial aspects at the CEJ and apically. The tissue grafts are sutured utilizing lateral continuous suturing techniques (Figure 9).

|

| Figure 10. Symmetrical zones of pinkish-white attached gingiva and absence of frenum. Note new correct natural length of teeth Nos. 22 through 27, allowing a clean, healthy smile. |

The final result achieved our initial goal. The lengths of all 4 incisors appear symmetrical and even, as shown in Figure 10. The lengths of all the incisors appear to be equal, whereas before, the lateral incisors appeared to be half the length of the central incisors. The gingival tissue surrounding the teeth now has a homogeneous pinkish-white color. It is a healthy zone of attached gingiva that is symmetrical in width as well as height, a beautiful background that now allows a healthy, cosmetic smile.

The periodontal treatment now establishes the background and opens the pathway for restorative materials to be utilized to help achieve the desired result. The restorative dentist uses appropriate materials to create certain aesthetic “illusions” that are needed to attain the desired goal.

Patients have their responsibility as well. Their hygiene maintenance must be demonstrated before any periodontal surgery or restorations are accomplished. When writing the treatment plan outline, the patient’s input must be included.17 This records and emphasizes the patient’s involvement and desires.

After the periodontal phase is completed and the appropriate healing time elapsed, the restorative phase can be completed. This doesn’t preclude conversation between the practitioners to adjust and make changes as each one proceeds. In this case, constant interdisciplinary communication and ongoing dialogue resulted in an extremely happy patient with a glowing smile.

CONCLUSION

In aesthetic dentistry, we must visualize the desired result before initiating treatment. This single statement is full of complexity, but in essence, our aesthetic goals should be determined before physical treatment is started in the patient’s mouth.

The result should be influenced by the patient’s aesthetic desires—what seems beautiful to them—as well as the experience of the practitioner. Patients’ ideas of cosmetic results are influenced by their social surroundings; eg, television and its advertisements, movies with their stars’ white teeth, and societal pressures. We must guide patients to avoid cyclical phases and fads that periodically influence them as consumers. However, the patient’s input must be part of the team’s goals so that everyone involved can visualize tomorrow’s treatment results today, before treatment begins.

References

1. Hoexter DL. Surgical techniques for a winning smile. Dent Today. 1994;13(6):46-49.

2. Hoexter DL. Cosmetic periodontal surgery, part 2: using variations of gingival graft techniques. Dent Today. 1999;18(11):110-115.

3. Abrams L. Augmentation of the deformed residual edentulous ridge for fixed prosthesis. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1980;1(3):205-213.

4. Hoexter DL. Periodontal aesthetics to enhance a smile. Dent Today. 1999;18(5):78-81.

5. Hoexter DL. Preprosthetic cosmetic periodontal surgery, part 1. Dent Today. 1999;18(10):100-105.

6. Gargiulo AW, Wentz FM, Orban B. Dimensions and relations at the dentogingival junction in humans. J Periodontol. 1961;32:261-267.

7. Goldman HM, Cohen DW. Periodontal Therapy. 4th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1968.

8. Hoexter DL. The background of a smile. Alpha Omegan. 1995;88(4):16-19.

9. Coslet JG, Vanarsdall R, Weisgold A: Diagnosis and classification of delayed passive eruption of the dentogingival junction in the adult. Alpha Omegan. 1977;70(3):24-28.

10. Evian CI, Cutler SA, Rosenberg ES, et al. Altered passive eruption: the undiagnosed entity. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;124(10):107-110.

11. Garber DA, Goldstein RE, Feinman RA. Porcelain Laminate Veneers. Chicago, Ill: Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc; 1997:6.

12. Goldstein RE, Belinfante L, Nahai F. Change Your Smile. 3rd ed. Chicago, Ill: Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc; 1997:6.

13. Smigel I. Dental Health, Dental Beauty. New York, NY: M Evans & Co; 1979.

14. Nabors CL. Repositioning the attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1954;5:38-39.

15. Grupe HE, Warren R. Repair of gingival defects by a sliding flap operation. J Periodontol. 1956;27:92.

16. Pennel BM, Tabor JC, King KO, et al. Free masticatory mucosa grafts. J Periodontol. 1969;40(3):162-166.

17. Hoexter DL. Closing the gap. A team-based treatment plan yields “you’ve changed my life” results. Dent Today. 2003;22(6):48-50.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to acknowledge E. Burger, J. Zeizel, and Jan Carter in the preparation of this article.

Dr. Hoexter is director of the International Academy for Dental Facial Esthetics and is a clinical professor of periodontics at the University of Pittsburgh. He received his degree from Tufts University, where he was also an adjunct professor of periodontics. He is a diplomate (implantology) of the ICOI, the American Society of Osseointegration, and the American Board of Esthetic Dentistry. He has lectured and published nationally/internationally and has been awarded 11 fellowships. He is in a private practice limited to periodontics, implants, and aesthetics in New York City. He can be reached at (212) 355-0004.