Today, dentists are finding that patients of all ages are demanding the use of materials and methods that will not only treat their immediate oral health condition but will also enhance their appearance and lifestyle. In particular, among the patients demanding more from their dental treatment are men and women aged 65 years and older who are living longer and settling for nothing less than aesthetic and natural-looking alternatives to resolve their dental problems. Given the fact that an estimated 57% of people between the ages of 65 and 74 and a total of 32 million Americans overall wear complete or partial dentures, the need to ensure that these appliances satisfy increasing patient expectations for aesthetics, fit, and function becomes obvious.

People who have reached the age of 65 will live an average of 17.8 additional years, and by 2010, the number of people aged 65 and older will be approximately 39 million. As a result, the number of people in the United States who will need complete dentures will increase over the next 20 years.1 Therefore, dentures will be required to function longer and with minimal problems.

Unfortunately, a recent research-based assessment of the quality of removable partial dentures (RPDs) found that a large number of them had defects. Maxillary dentures had more problems related to the presence of reline material and integrity defects, while mandibular RPDs demonstrated significantly more problems related to retention.2

The manner in which dentures function and fit clearly affects patients on a day-to-day basis. In a longitudinal clinical trial to assess the psychosocial well-being of subjects who were edentulous/edentate in one jaw, those who requested and received conventional dentures (not implant-supported) reported a significant improvement in satisfaction and health-related quality of life.3

It has recently been suggested that patients’ satisfaction with denture therapy may be higher if they are more fully informed about the limitations of the prosthesis they are about to receive.4 It is believed that by discussing patient-centered issues—with aesthetics and mastication being the 2 most frequent patient concerns— both the dentist and the patient will be better prepared to evaluate denture treatment options. In addition, dentists must provide patients requiring denture therapy with products that demonstrate the aesthetic qualities they desire, the fit and function they expect, and the durability and longevity their lifestyles demand.

CASE PRESENTATION

|

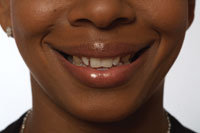

| Figure 1. Preoperative view of the patient’s dentition. |

A 77-year-old female presented with crowns on teeth Nos. 2, 4 through 11, 24, 25, 27, and 28. A removable prosthesis on the mandibular arch demonstrated an adequate framework condition, but the denture teeth were worn, severely in some areas (Figure 1).

Her periodontal condition on the maxillary arch was a case type III-IV with significant bone loss, periodontal pockets between 5 and 9 mm, tooth mobility, and some significant tooth displacement. The patient was adamant about not undergoing advanced periodontal intervention, specifically with respect to quadrant scaling and necessary surgery, since her prognosis was questionable. Additionally, she had been informed in the past that she would lose her teeth. She was advised at this time that if periodontal treatment was declined, then complete maxillary extractions would be necessary, which came as no surprise to her.

Her mandibular arch was a periodontal type II, with some pocketing and bone loss that was clinically salvageable with proper treatment. The patient was presently functioning with the precision mandibular RPD but was informed that it required a complete rebase with new teeth.

TREATMENT PLANNING

The patient was informed of various modalities of treatment and declined to attempt to salvage the remaining maxillary teeth. She requested complete maxillary extractions and a complete denture. However, owing to matters of modesty, she further declined any waiting time for healing and later fabrication of the denture. Fully informed of the problems associated with an immediate denture, she nevertheless requested a complete maxillary denture immediately following extractions.5 Additionally, the patient was concerned with completing both the maxillary immediate denture and mandibular denture rebase concurrently. It was therefore decided to fabricate the maxillary appliance alone and address the lower RPD rebase at a later date.

DENTURE MATERIAL AND OCCLUSION SELECTION

Because aesthetics and function were critical to the patient, a complete system of denture teeth was selected consisting of BlueLine denture teeth (Ivoclar Vivadent) in combination with the SR-Ivocap (Ivoclar Vivadent) denture base processing system. BlueLine denture teeth are available in all A-D shades, including 2 new bleach shades. They provide 20 molds for anterior teeth and incorporate different occlusal schemes (traditional lingualized occlusion, nonanatomic occlusion, modified lingualized occlusion, and semianatomic occlusion). A “facial meter” instrument that measures the interala and intercanthus distances is included along with a list of suggested tooth molds that would fit particular facial measurements. In addition, a reference table helps in selecting the most appropriate posterior denture teeth based on the anterior setup.

Lingualized occlusion (cusp upper/shallow cusp lower) was chosen for this case. It appears to be the most desired occlusal scheme for the majority of clinical situations because it does not compromise aesthetics and provides better stability.

IMPRESSION TAKING AND MODELING

The ESP (esthetic simplified predictable) denture technique was followed by the clinician and the laboratory and is described as follows:

|

| Figure 2. An AccuDent impression was taken. |

Study models were created, followed by actual refined impressions of the maxillary arch. Many material options exist for obtaining complete denture impressions, and more recent polyvinyl products demonstrate hydrophilic properties that make them ideal for complete denture impressions, which were required in this case. Here, a hydrocolloid system (Accudent System 1, Ivoclar Vivadent) was used (Figure 2). When used correctly, I [Dr. Esposito] have found that it produces high-quality removable impressions resulting in a distortion-free model that helps guarantee a properly fitting appliance requiring few adjustments. Alternate materials could include Siloflex (Spofa Dental) or Jeltrate Alginate (DENTSPLY Caulk).

|

| Figure 3. The first mounting setup of the teeth is completed for the wax try-in. |

|

| Figure 4. Occlusal view of the occlusal base and setup. |

|

| Figure 5. Anterior view of the occlusal base and setup. |

Once the models were obtained, a simple wax occlusal bite was taken and forwarded to the laboratory (BonaDent Dental Laboratories, Seneca Falls, NY, Figure 3) for use in fabricating a modified base plate with teeth set in the edentulous areas. The laboratory provided the processed base plate occlusal rim and split-cast setup (Figures 4 and 5) to the dentist.6 From the model, the technician removed teeth that were still in the patient’s mouth so she could assess the denture “template” prior to final fabrication.

Verifying Template

|

| Figure 6. Try-in of the occlusal base. |

|

| Figure 7. A face-bow record was taken using the Universal Transfer System. |

|

| Figure 8. The Universal Transfer System separated from the facebow with bite record. This can now be mounted on an articulator for final tooth placement and occlusion. |

At the dentist’s office, the occlusion was checked (Figure 6), and a facebow record was taken using the Universal Transferbow System (Ivoclar Vivadent, Figure 7), which registers the Camper’s Plane (CP) or the Frankfort Horizontal (FH). The adjustable earpieces enabled the clinician to properly align the facebow to the patient’s interpupillary line. Alternate systems could include the HANAU Modular Articulator or the Denar D5A. Once this was completed, the post dam area was noted on the model, and the entire case was returned to the laboratory along with instructions to mount and complete the case (Figure 8).

|

|

| Figure 9. The denture was invested using the Ivocap System for processing. | Figure 10. The denture was remounted after processing to verify occlusion and vertical dimension. |

At the laboratory, the SR Ivocap process (an injection system) was used to finish the case with the BlueLine denture teeth, since maxillary complete dentures fabricated with acrylic resin have been shown to exhibit clinically acceptable dimensional changes.7 Alternate processing systems could include the HI-I Pour (Fricke Dental) or the High Impact-54 (Lang). After mixing, the material was injected into the flask under pressure, and controlled polymerization cured the material from the anterior to the posterior of the denture. As the denture base material shrank during curing, the shrinkage was compensated for by additional material that was continually injected into the mold.8,9 This process is highly predictable and eliminates polymerization shrinkage, thereby preventing raised bites, spherical deformation, and the time-consuming occlusal adjustments of traditionally fabricated denture bases (Figures 9 and 10).10,11

|

|

| Figure 11. Finished denture product, ready for insertion. | Figure 12. Facial view of completed denture product prior to delivery to the dentist. Completely processed upper denture, facial view. |

|

|

| Figure 13. Case inserted immediately after complete maxillary extractions. | Figure 14. At the next day checkup, the patient was thrilled with the denture. There was noticeable swelling on the right side due to surgical root extractions. As a result, the patient’s upper lip was a little lower than it would normally appear. |

Once the completed case was returned to the dental office (Figures 11 through 14), the patient was instructed to present to the oral surgeon for extractions and insertion of the completed immediate maxillary removable denture.

CONCLUSION

The case presented posed a specific challenge based on the patient’s aesthetic requirements, which were compounded by her demand for an immediate prosthesis. When completed using the ESP technique and materials as described, the patient was more than satisfied with the aesthetics, while the fit, function, and precision were significant to the prescribing dentist.

References

1. Douglass CW, Watson AJ. Future needs for fixed and removable partial dentures in the United States. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87:9-14.

2. Hummel SK, Wilson MA, Marker VA, et al. Quality of removable partial dentures worn by the adult U.S. population. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;88:37-43.

3. Allen PF, McMillan AS. A longitudinal study of quality of life outcomes in older adults requesting implant prostheses and complete removable dentures. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14:173-179.

4. Mazurat NM, Mazurat RD. Discuss before fabricating: communicating the realities of partial denture therapy. Part II: clinical outcomes. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:96-100.

5. Mazurat NM, Mazurat RD. Discuss before fabricating: communicating the realities of partial denture therapy. Part I: patient expectations. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:90-94.

6. Langer A. The validity of maxillomandibular records made with trial and processed acrylic resin bases. J Prosthet Dent. 1981;45:253-258.

7. Polychronakis N, Yannikakis S, Zissis A. A clinical 5-year longitudinal study on the dimensional changes of complete maxillary dentures. Int J Prosthodont. 2003;16:78-81.

8. Jackson AD, Lang BR, Wang RF. The influence of teeth on denture base processing accuracy. Int J Prosthodont. 1993;6:333-340.

9. Jackson AD, Grisius RJ, Fenster RK, et al. Dimensional accuracy of two denture base processing methods. Int J Prosthodont. 1989;2:421-428.

10. Pow EH, Chow TW, Clark RK. Linear dimensional change of heat-cured acrylic resin complete dentures after reline and rebase. J Prosthet Dent. 1998;80:238-245.

11. Yeung KC, Chow TW, Clark RK. Temperature and dimensional changes in the 2-stage processing technique for complete dentures. J Dent. 1995;23:245-253.

Dr. Esposito received his DDS degree from the SUNY Buffalo School of Dental Medicine, and he is a former clinical instructor the school. He is a fellow of the Pierre Fauchard Academy and belongs to the American Dental Association, the Pennsylvania Dental Association, and the Monroe County Dental Society, where he was past president. A nursing home dental consultant at Laurel Manor and a moderator of DentalTown.com, he is the former vice-chairman of the peer review committee for the Pennsylvania Dental Association. He can be reached at (570) 421-0431 or at espo28@fast.net.

Mr. Fisher is the denture manager at BonaDent Dental Laboratories, Seneca Falls, NY, and has been in the lab industry for over 30 years. He can be reached at (800) 732-6222.