Communication between the dentist and dental laboratory has entered a renaissance in recent years. In the past, the dental laboratory technician was looked upon as a servant of the dentist rather than as an integral member of the restorative team. Years ago the number and type of laboratory-fabricated restorations were a mere fraction of those available today. Staying abreast of new technologies within the dental practice and changes in dental technology can be a quite a challenge.

As a clinician who works for a laboratory I see firsthand the good, the bad, and the ugly of the doctor/technician relationship. It all boils down to trustótrust that each party will listen to the otherís challenges and work together to achieve a common goal. Working together as a team from treatment planning to insertion can eliminate problems by considering both the clinical and laboratory technology issues. Considering both sides of these issues leads to one resultópredictable success for the dentist. Predictable success results in reduced chair time for adjustments at insertion and more chair time available for additional productive procedures.

This article will discuss all aspects of the communication process between the dentist and the laboratory. What are the responsibilities the laboratory has to the prescribing dentist? In what ways can the laboratory assist the dentist in the treatment planning and treatment execution phases? What are the methods of communication available to the dentist? Lastly, how do you effectively communicate using the laboratory prescription in a clear and concise manner?

|

|

Illustration by Cheryl Gloss |

TREATMENT PLANNING AND EXECUTION PHASES

How can the laboratory assist the dentist in the planning and execution phases of treatment? Working as a team member, the laboratory can assist in several ways. Communication between the dentist and the patient is critical during the treatment planning phase of a large aesthetic case. The patientís expectations may not match the dentistís expectations. Further, the patient may have specific ideas about how his or her smile should look. If the patientís concept does not match the fabricated reality, he or she will become dissatisfied with the end result.

Assistance in the material selection process is a service that a laboratory can provide its dentists. Often the difference between success and failure with material technologies is their proper selection for the case circumstances. The dental laboratory is in a prime position to experience success or failure with the myriad of dental restorative materials and their use in specific case circumstances. Therefore, the laboratory technician is able to offer valuable input as to material properties and their intraoral applications, limitations, and techniques for success.

Laboratory-fabricated diagnostic wax-ups are an excellent tool for the treatment planning phase. They can demonstrate for the dentist and the patient what the laboratory can accomplish with specific restorative materials. Many contours can be created in wax, but the specific dimensions required for a given material are an important consideration. Knowledge of the restorative material combined with the wax-up can guide the amount of preparation required to duplicate the result created in wax.

Laboratory-fabricated provisional restorations allow patients to function with their new teeth for a short period of time. During this time patients can evaluate the aesthetics of the provisional(s). If the patient dislikes an area, he or she can more effectively communicate to the dentist the specific area(s) to modify. A provisional restoration also allows the dentist to evaluate the patientís function and phonetics. This is especially important if there was significant incisal lengthening or diastema closure. The patient may have wanted longer teeth but is unable to function in that position due to occlusal interference. It is better to discover this in the provisional phase than to face a dissatisfied patient after the final case has been inserted.

Laboratory-fabricated prep guides quantify the amount of reduction necessary to achieve the result that the patient expects. The prep guide is made from the diagnostic wax-up with a specific material in mind. Without adequate reduction, the case cannot be made to mimic the diagnostic wax-up. Following the prep guide will allow the dentist to prepare the case so that the laboratory can duplicate the final restoration as close to the wax-up as possible.

METHODS OF COMMUNICATION

In most circumstances, the technician only has the information contained in the box. If there is one impression, one opposing model, one bite registration, and a lab prescription, then the amount of information available from these items is limited.

Study models are a helpful tool during all phases of restorative treatment. Incisal edge position, evidence of parafunction, the original width of the diastemas, and the contour of the virgin teeth can all be lost without study models. Properly mounted study models can confer information that may be missing in the final impression of the prepared teeth.

Diagnostic wax-ups are an excellent communication tool for the dentist to discuss proposed treatment with the patient. The diagnostic wax-up allows patients to communicate to the dentist their likes and dislikes based upon the dimensions of the wax-up. It is much easier for patients to point to a specific area and ask for it to be narrowed or broadened versus attempt to describe their concept of how they envision their smile. In the end, a diagnostic wax-up can reduce costly remakes due to miscommunication of size, shape, and contour.

Model(s) of the provisional restoration(s) help guide the laboratory to provide the size, shape, shade, and contours that the dentist has created and the patient has approved. The models are especially helpful if the patient has worn the provisional restorations for at least a week. This trial run of their teeth allows patients to comment on the aesthetic and functional issues of their provisional restorations. Other than proper treatment planning, this can be one of the most important financial and time-saving steps of the restorative phase of treatment. As long as an adequate amount of reduction has been accomplished for the material selected, there will be no surprises when the final restorations mimic the provisional restorations.

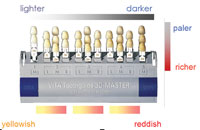

Photographs can be worth a thousand words. Investing in a good digital camera and a CE course to learn effective photographic techniques is an invaluable communication tool. A properly exposed and clear photograph can yield a wealth of information about contour and anatomy. It is much easier to follow a photograph for the location of a hypocalcified area or mame-lon than it is to attempt to draw or describe this area in writing. One thing a photograph cannot convey at this time is shade. We cannot choose the shade of a restoration with a single photograph. Other methods can help utilize photography for a shade match, but at this time, a picture alone cannot convey the shade accurately.

THE LABORATORY PRESCRIPTION

A specific delivery date is extremely important. The term ASAP is too frequently used. ASAP means as soon as possible for the laboratory. Busy times of the year for dental laboratories mimic those of dental practice. If you use ASAP as a return date, then you may have situations when the case is not returned in time to meet your schedule. If your laboratory routinely delivers your single-unit PFM crowns within a week, but it is a busy month for the laboratory, the PFM might be returned in two or two-and-a-half weeks. This will depend on the number of cases in the laboratory that have specific return dates. Your case will be fabricated when it fits into the schedule along with the cases that have specific return dates. If you ask for a specific date, and if the laboratory is unable to accommodate the request, you will be notified of the exact delivery date. In this way your administrative team will always know exactly when a case is due to be delivered.

Clear handwriting is an important component of the laboratory prescription. Com-municating what is requested for a patientís case can be a challenge. However, this challenge can be compounded when the handwriting cannot be interpreted. The laboratory should never have to interpret your writing. Remakes can be costly for the dentist and the laboratory. It can be time-consuming for both parties if the laboratory needs to call the dentist regularly to interpret his or her handwriting. Many software packages are designed for the dental practice that have the capability to print the laboratory prescription. You can save time on your routine cases by printing the prescription because all of the necessary information has been pre-entered into the system in a clear and concise manner. Using these types of systems can eliminate miscommunications due to penmanship.

It is important not to use nondental terms for reasons similar to those about clear handwriting. Asking for toilet bowl design, a redneck face-bow, or use a dummy (pontic) can cause a great deal of confusion. We have our own terminology in dentistry and we must use it correctly so there is no confusion about what the dentist requests from the laboratory. As in the case of clear handwriting, it can be time-consuming if the laboratory calls the dentist regularly to interpret his or her own version of dental terminology.

Listing the items that you send with a case can accomplish 2 things: first, it serves as a reminder for the person packaging the case to include all of the necessary items, and second, it serves as a double-check when the laboratory inventories these items when they are unpacked from the box. In addition, the person at the office and the person at the laboratory should initial the inventory. In this way we can work together to account for any missing materials such as an opposing model or bite registration.

Specify the type and design of the restoration. For example, what type of alloy would you like for your PFM or full cast restoration? The lab technician can choose for you, but if he or she does not know that the patient is allergic to base metals, then the technician might make the wrong choice. What type of all-ceramic crowns would you like? The lab technician can choose for you, but if he or she does not know that the tooth was restored with a metal post, then the technician might choose a restoration that is translucent, and the metal will show through the final crown. What about the anatomical design and/or the design of the embrasures and pontics? Many of these issues can be addressed if your laboratory has your standard preferences on file. However, if these items are not specified, then the lab is forced to do one of two things: either pull you away from your patients and ask you what material or design you desire for the case, or assume what you need and possibly make the wrong decision.

Create internal check lists for each type of case so that all necessary items are delivered to the laboratory. Most practices have one person who packages each case for the doctor. However, if that person is busy or out sick, necessary items can be left out of the box. Posted check lists for each type of case sent to a laboratory take all the guesswork out of packaging the case for shipment. It also serves as a subtle reminder to include certain items for one type of case and additional items for other types of cases. The laboratory may not need a face-bow record for a single crown, but it does need one for a large anterior case or a roundhouse bridge.

SUMMARY

Working as part of your team, your dental laboratory can increase your predictable success and decrease the stress of daily practice. This partnership should begin during the treatment planning phase and continue through to the insertion appointment. Many dentists are beginning to view their laboratory technician as a bonafide member of their patient care team.

Thorough communication on both sides is crucial to reaching this predictable success. A trusting relationship will enable the dentist and the laboratory technician to communicate effectively. The laboratory must take the responsibility to communicate its concerns to the dentist, just as the dentist must take the responsibility to communicate effectively with the laboratory his or her needs and desires for each case.

When effective communication techniques are followed, everyone is a winner. The dentist is more productive per hour and has reduced stress. The dental laboratory does not have to bear the burden of remakes, and spends less time on the phone or sending e-mail for routine cases. And most importantly, the patient receives an exceptional restoration that meets his or her expectations.

In the end, the true measure of a great relationship between the dentist and the laboratory is happy patients who refer friends and family to your practice for years to come.

Dr. Mendelson is an alumnus of the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery and joined Americus Dental Labs in late 2004 as its director of education. He has been involved in all aspects of dentistry for 19 years and primarily functions as the clinical liaison between the dentist and the laboratory. Dr. Mendelson lectures nationally and is an adjunct clinical faculty member of Nova Southeastern University. He is a member of the Florida Dental Association, National Speakerís Association, and OSAPís Speakers Bureau. He can be reached at (800) 237-1723 or martinm@americus-clearwater.com.