The United States now has the largest and fastest-growing population of older adults in its history. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC)1, the number of older Americans, aged 65 or older, will double during the next 25 years due to 2 factors: longer life spans and aging baby boomers. By 2030, one in 5 Americans will fit within the older adult classification.1

In the geriatric population, chronic diseases often take precedence over dental problems. Research shows that older Am-ericans are at greater risk for oral health problems than any other population, due to lowered resistance to disease, existing medical conditions, difficulty in accessing dental services, and increased dependence on others for care.2

VARIATIONS IN SELF-SUSTAINABILITY

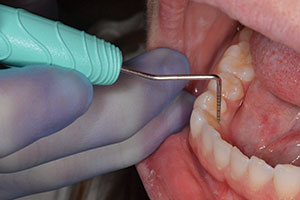

|

|

Illustration by Nathan Zak

|

The geriatric population is a diverse group that ranges in self-sustainability from independent living to complete reliance on others for assistance with activities of daily living. Older adults’ quality of life is determined by a combination of factors, in-cluding self-sustainability, medications, physical and mental health, financial limitations, and oral health. These factors play a vital role in assessing our patients’ needs during inoffice dental visits as well as in designing their at-home preventive care. Keep these contributing factors in mind when offering maintenance tips, suggesting at-home care products, and setting future appointments.

A LINK TO SYSTEMIC HEALTH

The exploding geriatric population, coupled with recent discoveries surrounding links between oral health and systemic health, make it increasingly important for the dental community to be prepared to treat geriatric patients in the dental office or where they live. Ongoing research suggests that periodontal bacteria entering the bloodstream may be linked to conditions such as respiratory disease, diabetes, heart disease, increased risk of stroke, and osteoporosis. Studies further suggest that periodontal bacteria can pose a threat to people whose health is already compromised by these conditions.3 In light of this growing body of research, comprehensive dental care becomes increasingly important to help improve our geriatric patients’ quality of life and outlook.

ENCOURAGING SENIOR VISITS AND PREVENTIVE CARE

A natural part of aging can be dramatically diminished pain perception, which can easily mask the need for professional dental care.4 Additionally, many individuals accept oral problems and tooth loss as inevitable results of aging, making dental visits unimportant to them.5 These patients may not understand that regular dental appointments become increasingly important as they age or that professional care can positively impact their quality of life and attitude. Given this, the entire dental team needs to encourage older patients to maintain daily oral hygiene as well as regular dental visits.

This can also hold true for elderly individuals with dentures who believe their prostheses to be a final “cure” for their tooth loss and see no need to return to the dentist for regular check-ups. While it is true that more elderly people are keeping their teeth than ever before, the number of people wearing full or partial dentures is on the rise as well. The Centers for Disease Control6 reports that in 1991, 33.6 million people needed one or 2 complete dentures and this number is predicted to reach 44 million by 2020.

With patients who wear complete or partial dentures it is just as important to stress proper care and maintenance procedures as it is to encourage follow-up appointments. One report showed that only 19% of denture wearers remember their dental professionals’ instructions regarding regular checkups.7 In particular, it is advisable to stress oral re-evaluations for denture patients when considering bisphosphonate therapy.8 By remembering to emphasize these details to your elderly patients and explain why it is important they follow your advice, you can help make check-ups routine and not just a painful emergency.

STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESS

Dental care for seniors has always posed unique challenges. It requires understanding and sensitivity to the medical, psychological, social, and financial status of elderly patients. When providing care to aging patients with physical and sensory limitations, the entire dental team needs to ensure that patients feel welcomed and comfortable. Start by reviewing office signage and lighting. Include in your reception room magazines that encompass geriatric oral health. Be sure that written information such as health history forms, business cards, brochures, appointment cards, and postcards are available in large-print.9 The National Institute on Aging offers an excellent and comprehensive guide called “Making Your Printed Health Materials Senior Friendly,” which can be downloaded by visiting nia.nih.

gov/HealthInformation/Publications/srfriendly.htm. Extra reminders of appointments may also be appreciated; take care to leave clear, understandable messages on answering devices.

Arrange furniture to accommodate wheelchairs and walkers, and to reduce or eliminate barriers. Be sure to offer supportive armchairs (that are not too deep or too low) in easy-to-access areas of the reception room.9 Similarly, it may be helpful to raise the upright dental chair from its lowest position when elderly patients are entering and exiting. For wheelchair transfers, always position the seat of the dental chair at the same height as the patient’s wheelchair. Pay particular attention to obstacles frequently faced by seniors and make every effort to understand and adapt to their special needs, even if it means scheduling extra time.

BEFORE THE EXAM

Dental providers will find more success when they communicate clearly, respectfully, and reassuringly with elderly patients. Speak slowly and directly to the patient.10 Do this understanding that it is worth the extra time it may take for them to respond. Longer appointments may need to be considered in order to accommodate the pace and special needs of geriatric patients.

Knowledge of the patient’s medical and dental history aids the practitioner in planning and providing safe, personalized, appropriate, and comfortable treatment. An accurate health history is more than a legal necessity. For medically compromised patients, it can mean the difference between life and death. As people age, their healthy therapeutic window narrows, and even slight alterations in the medical condition can cause significant changes. Awareness of systemic changes can also direct attention to subtle manifestations in the oral cavity. Reviewing histories at each appointment provides not only essential updates, but impresses upon the patient that what happens in the mouth affects the rest of the body, and vice versa.

Given the variations in self-sustainability of geriatric patients, it may be necessary to ask the caregiver or representative from the long-term care facility to bring or fax a list of current medications. Always inquire whether the individual has any swallowing difficulties (dysphagia or aphagia) that may require adjustments in patient positioning, water usage, suctioning, or rinsing in order to avoid aspiration problems during treatment. Swallowing and expectoration limitations also indicate special consideration when recommending therapeutic rinses and fluoride gels. Remineralizing agents (MI Paste [GC America]), which are safe to swallow and simple to apply, can be an appropriate alternative to daily fluoride use.

ENCOURAGING CAREGIVER INVOLVEMENT

Geriatric patients may have difficulty performing routine oral hygiene procedures due to physical limitations and/or memory problems, making the instruction and coordination of home care particularly important. Because of the possibility of actively declining skills, every dental hygiene visit should include an assessment of the patient’s manual dexterity. As reliance on others grows, include the caregiver in homecare instructions. Make specific suggestions as to how the caregiver can supplement the patient’s abilities and daily efforts. Demonstrate the use of power brushes and interdental aids and, most importantly, have the caregiver don gloves and participate. Dental professionals need to make sure patient and caregiver completely understand the oral care they will be practicing at home.

Emphasize that homecare combined with regularly scheduled preventive and restorative care are important components of the patient’s overall health and quality of life. The following guidelines may be shared with patient and caregiver:

First, brush teeth and gumline with toothbrush dipped in a mouthwash designed for Dry Mouth. Not using toothpaste facilitates better visibility for the caregiver, as well as the opportunity for the patient to explore with the tongue for lingering plaque. Fluoride toothpaste may be applied once all plaque is removed.

Second, apply lip balm and oral moisturizing gels during oral care and throughout the day as often as comfort demands.

Third, apply appropriate remineralizing agents daily to control xerostomia-induced caries.

Fourth, denture wearers need to be aware that some regular toothpaste contains abrasives that may dull and scratch dentures, promoting bacteria build-up. Dentures should be brushed daily with a denture-specific, non-abrasive cleanser, such as Fresh Cleanse antibacterical foaming cleanser (GlaxoSmithKline). These microclean tough stains and kill odor-causing bacteria. Also, acrylic surfaces naturally have microscopic pores that have been shown in studies to harbor bacteria. Soaking dentures in some commercial cleansers, such as Polident (GlaxoSmithKline), can kill 99% of bacteria, effectively disinfecting prostheses.11

ORAL CARE AND NURSING HOME PATIENTS

As the elderly population grows, so does the number of adults who move into nursing homes and require assistance with their activities of daily living. While providing adequate oral hygiene in community care facilities is an achievable goal, in reality most facilities overlook this duty.5

According to a study by the Academy of General Dentistry,2 nursing home residents have increased risk for dental problems compared to seniors who live independently. Approximately 5% of Americans over the age of 65 (currently about 1.75 million people) are residents of long-term care facilities where they may have problems accessing adequate dental care.12 The problem of neglect and high levels of unmet needs among elderly residents of nursing homes has been widely documented. A survey of 1,063 residents in 31 nursing homes found that the greatest single need among dentate elderly was for routine oral hygiene.13

| Table. The Following Tips May Be Suggested to Caregivers of Nursing Home Patients. |

|

Dental health often declines precipitously as elderly patients become unable to perform their own daily hygiene and arrange professional dental visits. Therefore, until onsite dental clinics and effective daily oral hygiene programs are established in long-term care facilities, dental professionals need to encourage caregivers to play an assertive role in meeting the dental needs of residents. (Table).

CONCLUSION

Geriatric healthcare is complex. The medical team’s goals include maximizing each person’s function, health, independence, and quality of life. Ideally, every geriatric team should include a dentist and/or dental hygienist to promote optimal quality of life through proper oral care.5 Poor dental health does not have to be an inevitable consequence for America’s aging population. By keeping abreast of the complex issues that impact geriatric dental care and offering treatment that takes into consideration the physical, mental, and social status of older adults, dental healthcare providers can enhance their older patients’ health, thus enabling them to enjoy healthier, longer lives with improved comfort, outlook, and quality of life.

References

- Healthy aging for older adults. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/aging/index.htm. Accessed May 18, 2007.

- Nursing home oral health care. Academy of General Dentistry Web site. http://www.agd.org/public/oralealth/Default.asp?IssID=328&Topic=S&ArtID=1316#body. Updated February 2007. Accessed September 15, 2008.

- Parameter on periodontitis associated with systemic conditions. American Academy of Periodontology. J Periodontol. 2000;71(5 suppl):876-879.

- Elliot-Smith S. The changing face of oral health in the baby boom generation. Access. 2007;21:14-19.

- Slavkin HC. Maturity and oral health: live longer and better. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:805-808.

- Douglass CW, Shih A, Ostry L. Will there be a need for complete dentures in the United States in 2020? J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87:5-8.

- Melton AB. Current trends in removable prosthodontics. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131(suppl):52S-56S.

- Suzuki JB, Klemes AB. Osteoporosis and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Access. 2008;22(suppl):2-13.

- Matear D, Gudofsky I. Practical issues in delivering geriatric dental care. J Can Dent Assoc. 1999;65:289-291.

- Gluch J. Customizing oral hygiene care for older adults. Contemporary Oral Hygiene. April 2003; 22-27.

- Shay K. Denture hygiene: a review and update. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2000;1:28-41.

- Guay AH. The oral health status of nursing home residents: what do we need to know? J Dent Educ. 2005;69:1015-1017.

- Kiyak HA, Grayston MN, Crinean CL. Oral health problems and needs of nursing home residents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:49-52.

Ms. Van Sant has been providing onsite dental hygiene services in long-term care facilities throughout South Carolina’s upstate region since 2002. She received her BS in Dental Hygiene from the Medical College of Georgia in 1975, and is a member of ADHA and the Special Care Dentistry Association. Her experience includes working as a public health dental hygienist, clinical periodontal therapist, and community oral health educator. She can be reached via e-mail at residental@charter.net or visit residental.net.