|

|

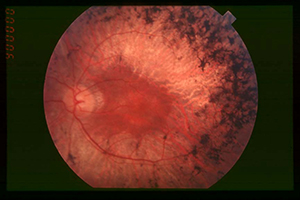

A dominant male cichlid looms from the dark waters of his territory, ready to fend off subordinate males who might try to cross the boundary. (Credit: Todd Anderson) |

Subordinate cichlid fish have an impressive ability to rise to the procreative occasion with stunning speed if the alpha male—usually the only one to reproduce—abdicates.

In cichlid society, the second-string male fish hang around the fringes, keeping their reproductive systems idling to the point they can practically pass for females. But when the dominant male disappears, the beta boys have turned out to be unexpectedly fast on the spawn.

“It is amazing how quickly they can recover from being down and out,” said Russ Fernald, professor of biology at Stanford University.

A newly self-appointed alpha begins “acting alpha” within a few minutes of the disappearance of the old top dog. It can spawn successfully within a few hours and will have its sperm in top reproductive condition in less than a day.

All this from a creature that for weeks has endured drastically lowered hormone levels, severely shrunken testes, and a noticeable (and perhaps understandable) pallor compared to the brightly colored alphas that have been knocking them around and monopolizing all the females.

“Even the neurons in the subordinate males’ brains that control their reproductive system are very small,” said Karen Maruska, a postdoctoral researcher in Fernald’s lab and a coauthor of the paper. “We originally thought that these males just couldn’t do this, that they didn’t have sperm, that they weren’t reproductively competent.”

It turns out that even though the subordinate males have very small testes compared to a dominant male, they still keep making sperm on the sly. Their reproductive system hasn’t been throttled, just throttled down.

Even more surprising is the increased viability of an ascendant cichlid’s sperm.

“There is a signal from the recognition of social opportunity all the way into the gonads to change the quality of the sperm,” Fernald said. “It was completely unexpected that the reach of social information would go that deep so quickly.”

Researchers had thought that if the social change did trigger a physiological signal, it might be a slow cascade of changes that eventually could result in heightened reproductive ability, but were surprised by the subordinate male’s rapid response.

“Reproduction is so important that evolution has favored the rapidly ascending male,” Fernald said.

Other species, including white rhinos, mice, Atlantic salmon and baboons, use the same approach where dominant males engage in “social suppression” to keep subordinate males from breeding, resulting in a variety of changes in behavior and physiology.

Often those males reduce the amount of energy they put into sperm production, since that energy is pretty unlikely to bear fruit.

But while much is known about physiological changes that occur in a male when it is being socially suppressed, little has been known about how such a male’s physiology responds when it suddenly ascends to dominance and has the chance to reproduce, particularly the cellular changes that occur within the testes.

“You can’t just go in and sacrifice a rhinoceros and see how its testes are working,” Fernald said.

Hence his lab’s focus on the African cichlid, a relatively small fish native to Lake Tanganyika in East Africa. More abundant than rhinos and much less dangerous, but practicing social suppression in a way fundamentally similar to rhinos and other animals, cichlids make an excellent model for study.

Model behavior

For the study, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, researchers placed two males of the same size into a tank with three or four females and half of a terra cotta pot, which served as the territory. By the time the fish had been in the tank for a day, one male would become clearly dominant, the other subordinate.

The researchers monitored each tank for four to five weeks, the same span of time that a dominant cichlid in the wild typically controls a territory before succumbing to predation or a successful coup by another cichlid.

If the same male maintained dominance the whole time, he would then be removed from the tank and the behavior of the subordinate male observed.

After allowing the ascendant male 24 hours to enjoy his new status, researchers ended his reign, removing him to analyze changes in his physiology and sperm quality.

“It was clear they were investing energy in reproduction, so that when they became dominant males, they could switch very quickly,” says undergraduate Jacqueline Kustan, the study’s lead author.

The early sperm gets the roe

It makes sense that a male cichlid’s reproductive system would keep humming along in low gear, Maruska said, because he must be prepared to perform quickly.

“He’s not going to be able to hold that territory and convince females to come in and spawn with him if he doesn’t have the sperm,” she said. “That is probably one of the reasons this mechanism persists, so that he can basically back up his actions.”

It is likely that methods to give a male’s physiology a quick kick into reproductive high gear are present in other species. In every known vertebrate social system, males are competing to get access to females and in most cases use aggression to fight off opponents.

“The victors are the ones that get to reproduce and I would predict that they have mechanisms similar to this one, where the nondominant male, as quickly as he can, will become able to reproduce,” he said. “That is the name of the game.”

|